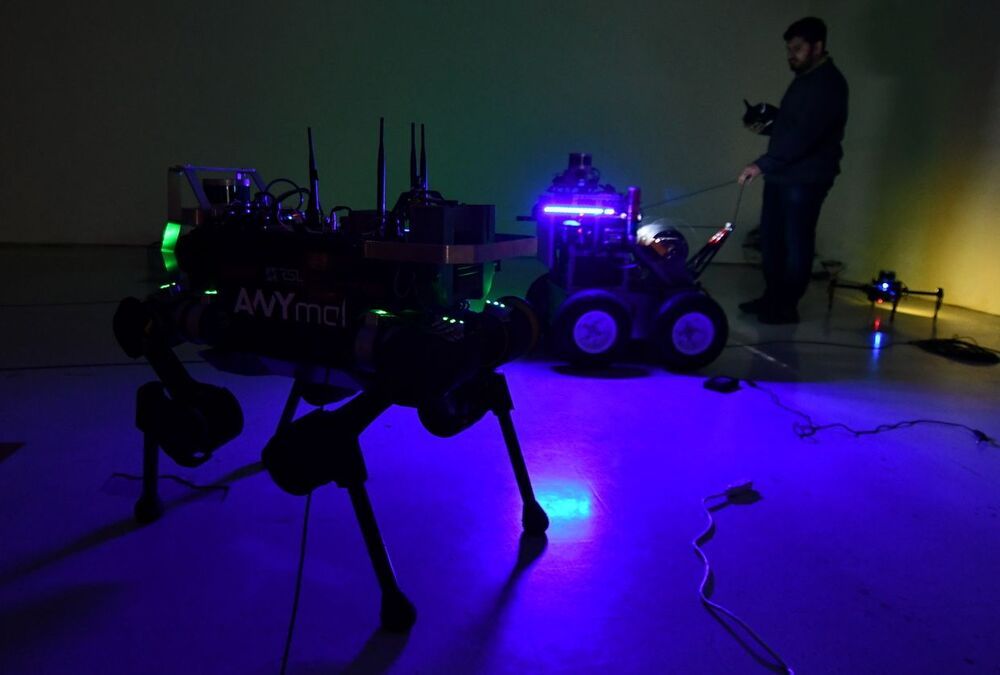

Three years of underground robotics competitions culminate in a final event in September with $5 million in prize money.

The DARPA Subterranean Challenge Final Event is scheduled to take place at the Louisville Mega Cavern in Louisville, Kentucky, from September 21 to 23. We’ve followed SubT teams as they’ve explored their way through abandoned mines, unfinished nuclear reactors, and a variety of caves, and now everything comes together in one final course where the winner of the Systems Track will take home the $2 million first prize.

It’s a fitting reward for teams that have been solving some of the hardest problems in robotics, but winning isn’t going to be easy, and we’ll talk with SubT Program Manager Tim Chung about what we have to look forward to.

Since we haven’t talked about SubT in a little while (what with the unfortunate covid-related cancellation of the Systems Track Cave Circuit), here’s a quick refresher of where we are: the teams have made it through the Tunnel Circuit, the Urban Circuit, and a virtual version of the Cave Circuit, and some of them have been testing in caves of their own. The Final Event will include all of these environments, and the teams of robots will have 60 minutes to autonomously map the course, locating artifacts to score points. Since I’m not sure where on Earth there’s an underground location that combines tunnels and caves with urban structures, DARPA is going to have to get creative, and the location in which they’ve chosen to do that is Louisville, Kentucky.