AIR PLASMA BREATHING via Ground Stations, in lieu of on-board energy supply: Recently, both a German team and a Chinese team have demonstrated jet engines capable of as much thrust as a traditional jet engine, but powered only by electricity. In both cases, the engine uses large amounts of energy to turn ambient atmosphere into plasma, then jetison it via magnetic nozzles. This is to be differentiated from space ion drives, which use tiny amounts of fuel, ejected at high velocities to slowly accellerate a vehicle in free space. By contrast, this new type of engine has huge amounts of fuel available to it in the form of the ambient atmosphere. Such craft could operate in any planetary atmosphere in our solar system, whether on Venus, Earth, Mars, the gas giant or ice giant planets. The only bottleneck holding this type of engine from replacing all current airplanes is the lack of a sufficiently dense on-board energy source. The most obvious enabling technology which will allow this new type of jet, which will require no fuel for its entire lifetime—since its fuel will be the atmosphere—is fusion energy. Fusion is dense enough to fit into a small package, easily mounted on an airplane. Until fusion is obtained there is one other possibility which is currently available, which is beaming energy to a flying vehicle from ground stations. An air-plasma-breathing vehicle, whether a self-standing airplane, or a partial booster phase for a rocket to low-earth-orbit, would have to follow a trajectory within direct line-of-sight of a series of ground beaming stations. A string of such stations would be akin to a land highway, a corridior within which air traffic or space-bound vehicles could travel. Such a corridior would be easy to create. Even over ocean, aircraft carriers or other nuclear vessels could transmit large amounts of energy to such vehicles. For rockets travelling to orbit, such a system would reduce reaction mass, since a portion of its fuel would not be carried by the vehicle. File: compilation of papers on beamed energy for flying vehicles:

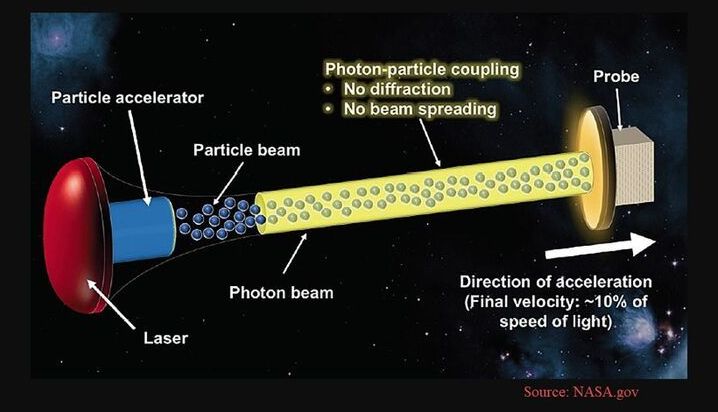

Beam-powered propulsion, also known as directed energy propulsion, is a class of aircraft or spacecraft propulsion that uses energy beamed to the spacecraft from a remote power plant to provide energy. The beam is typically either a microwave or a laser beam and it is either pulsed or continuous. A continuous beam lends itself to thermal rockets, photonic thrusters and light sails, whereas a pulsed beam lends itself to ablative thrusters and pulse detonation engines.

The rule of thumb that is usually quoted is that it takes a megawatt of power beamed to a vehicle per kg of payload while it is being accelerated to permit it to reach low earth orbit.

This technology is also part of the research aim of the To The Stars Academy of Arts & Sciences. I compiled the below documents to explore the research the U.S. Government and Military has already collected and what they have tested in regards to the technology.