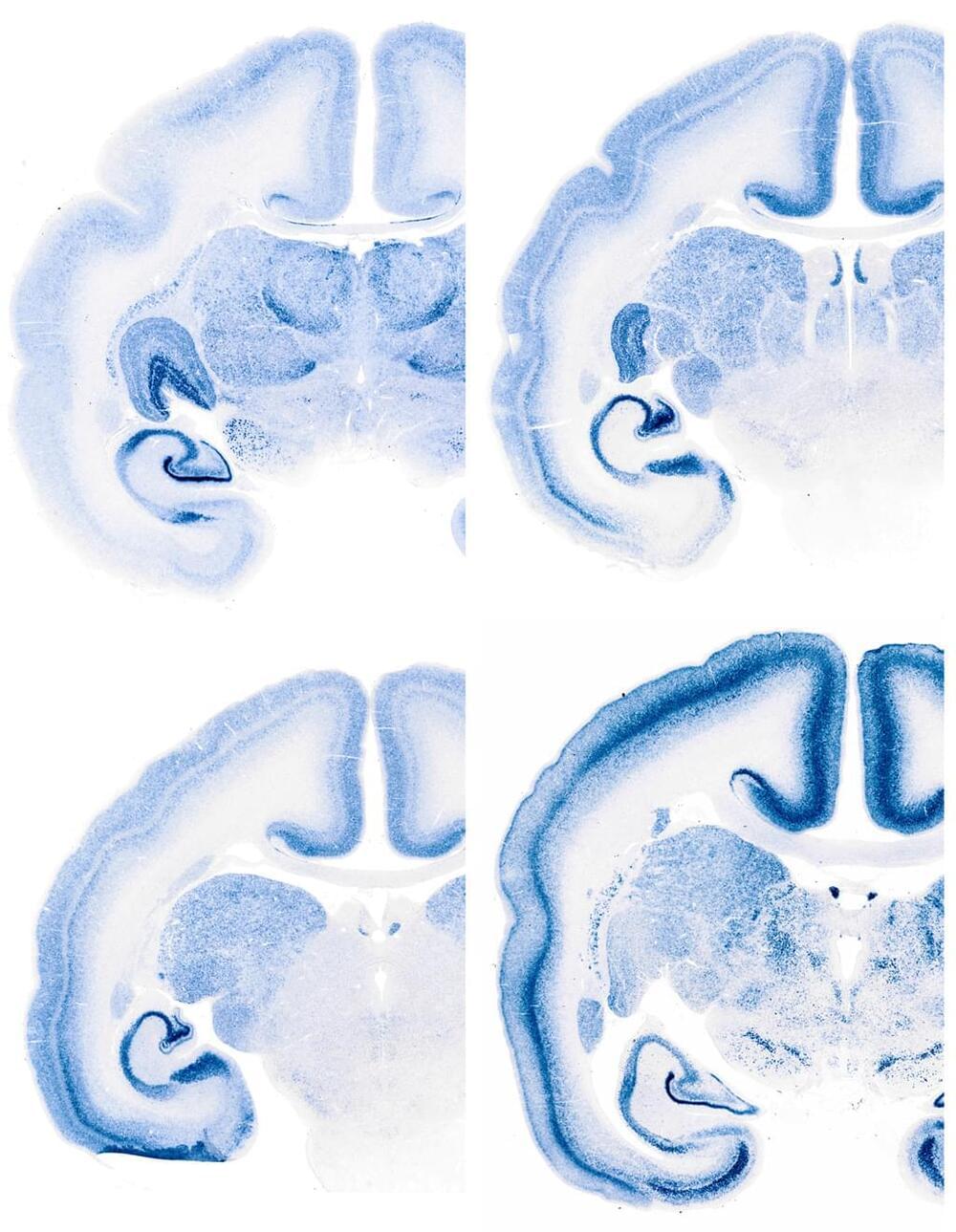

How the brain functions is still a black box: scientists aren’t even sure how many kinds of nerve cells exist in the brain. To know how the brain works, they need to know not only what types of nerve cells exist, but also how they work together. Researchers at the Salk Institute have gotten one step closer to unlocking this black box.

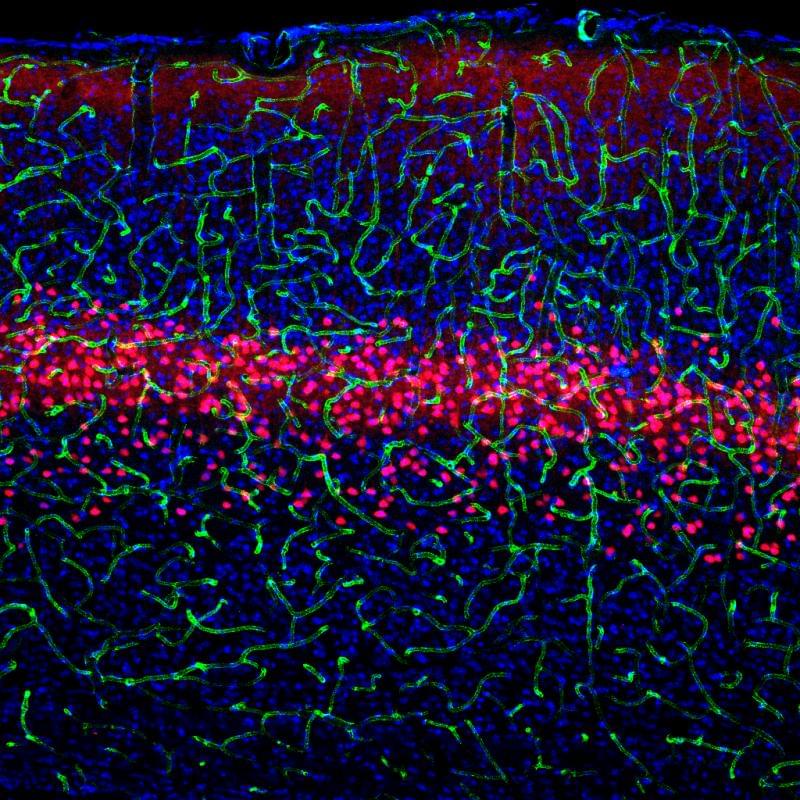

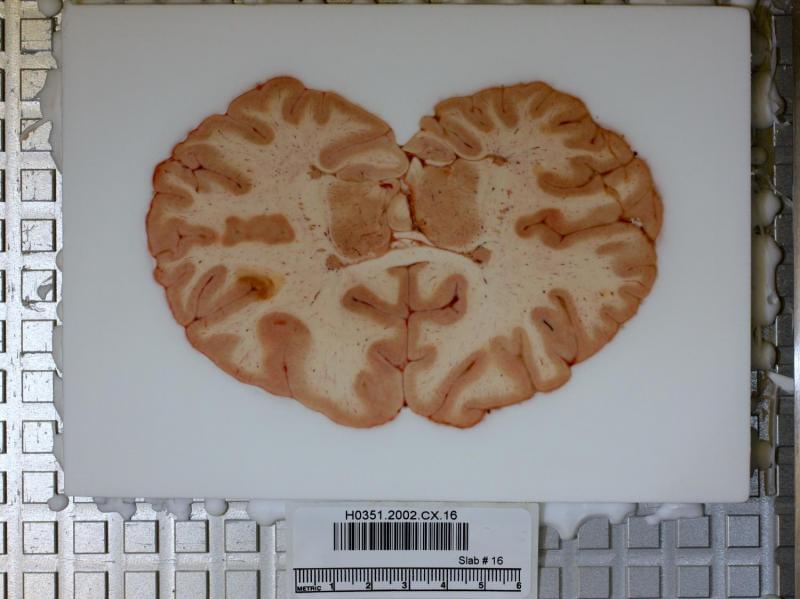

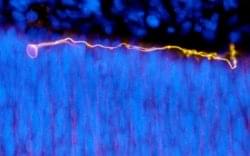

Using cutting-edge visualization and genetic techniques, the team uncovered a new subtype of nerve cell, or neuron, in the visual cortex. The group also detailed how the new cell and two similar neurons process images and connect to other parts of the brain. Learning how the brain analyzes visual information at such a detailed level may one day help doctors understand elements of disorders like schizophrenia and autism.

“Understanding these cell types contributes another piece to the puzzle uncovering neural circuits in the brain, circuits that will ultimately have implications for neurological disorders,” says Edward Callaway, Salk professor and senior author of the paper published December 6 in the journal Neuron.