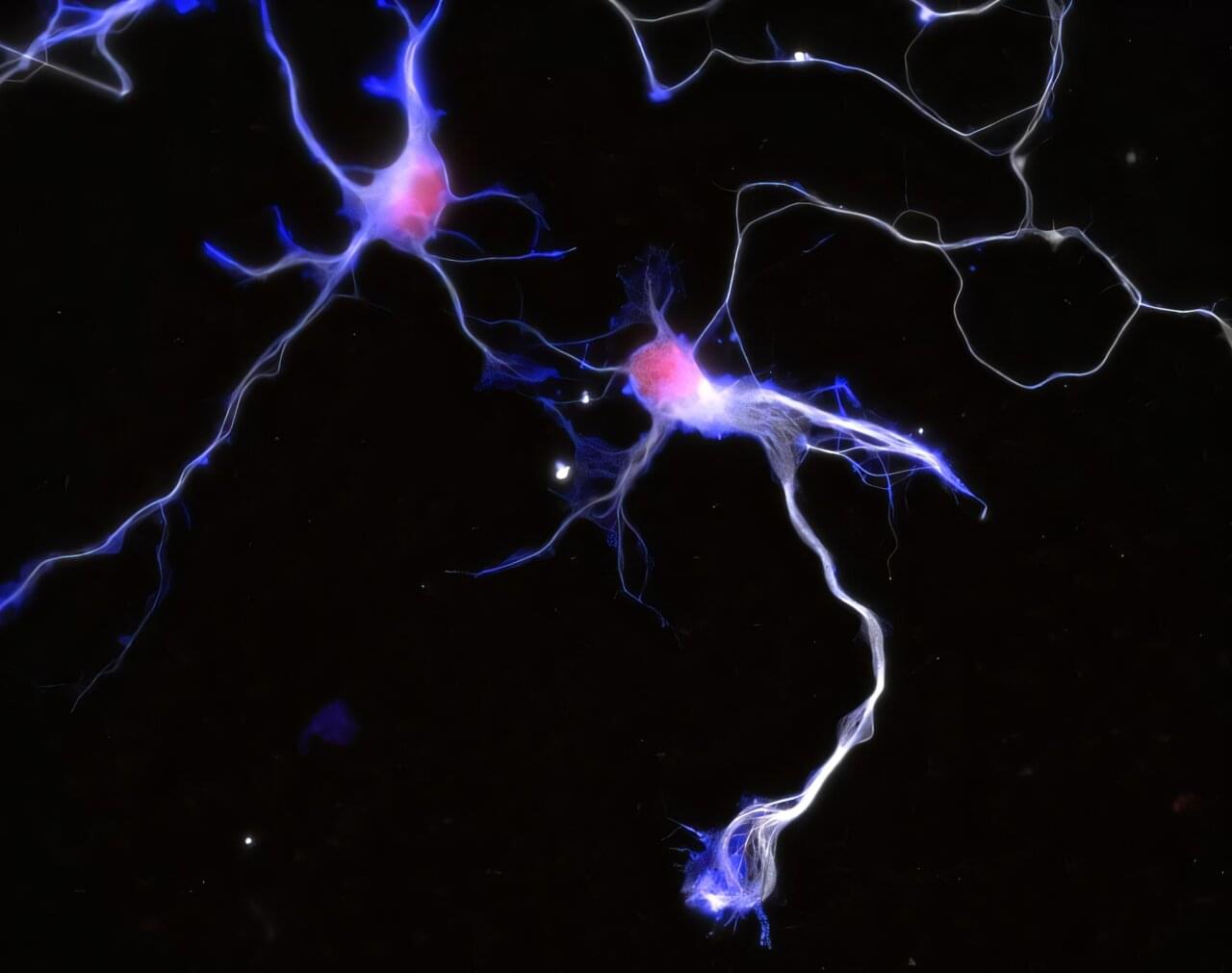

In the brain, highly specific connections called synapses link nerve cells and transmit electrical signals in a targeted manner. Despite decades of research, how synapses form during brain development is still not fully understood.

Now, an international research team from the Max-Planck-Zentrum für Physik und Medizin, the University of Cambridge, and the University of Warwick has discovered that the mechanical properties of the brain play a significant role in this developmental process. In a study recently published in Nature Communications, the scientists showed how the ability of neurons to detect stiffness is related to molecular mechanisms that regulate neuronal development.