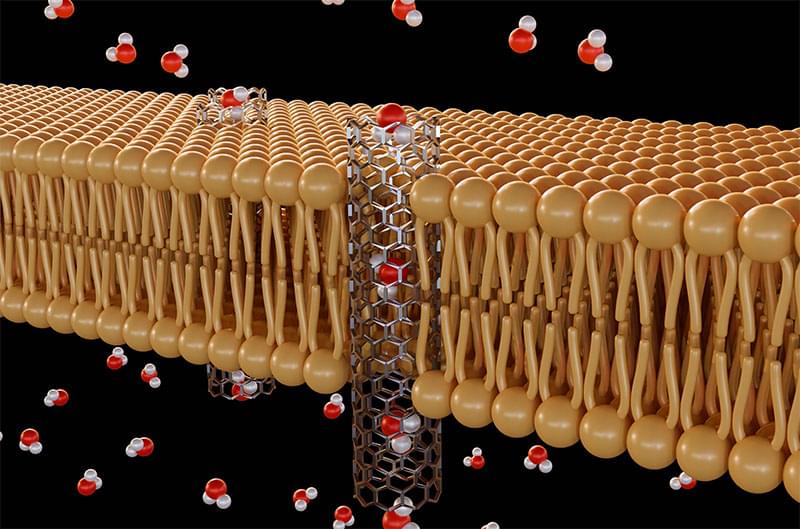

In the world of nanotechnology, the development of dynamic systems that respond to molecular signals is becoming increasingly important. The DNA origami technique, whereby DNA is programmed so as to produce functional nanostructures, plays a key role in these endeavors. Teams led by LMU chemist Philip Tinnefeld have now published two studies showing how DNA origami and fluorescent probes can be used to release molecular cargo in a targeted manner.

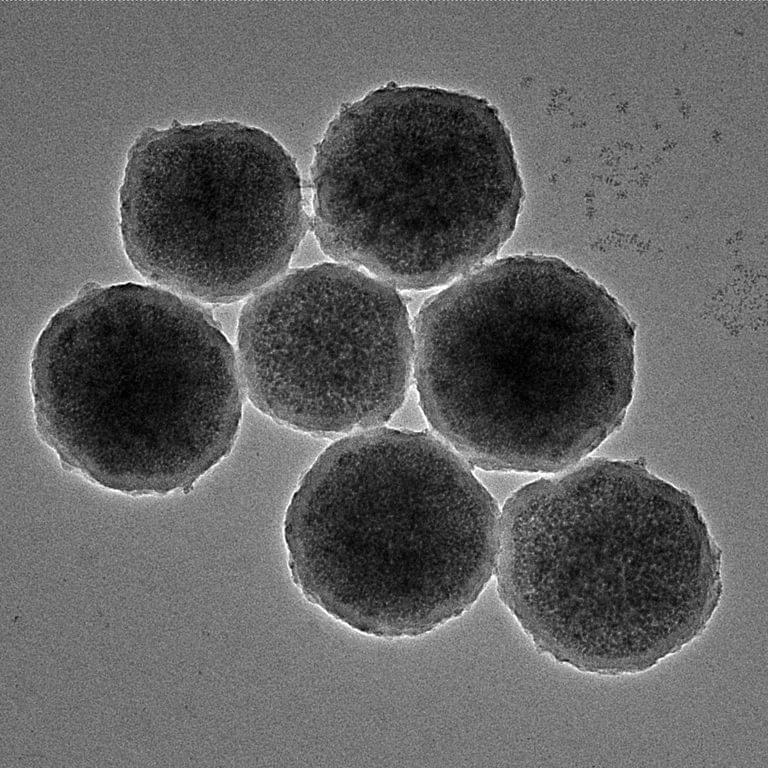

In the journal Angewandte Chemie (“DNA Origami Vesicle Sensors with Triggered Single-Molecule Cargo Transfer”), the researchers report on their development of a novel DNA-origami-based sensor that can detect lipid vesicles and deliver molecular cargo to them with precision.

The sensor works using single-molecule Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET), which involves measuring the distance between two fluorescent molecules. The system consists of a DNA origami structure, out of which a single-stranded DNA protrudes, which has been labeled with fluorescent dye at its tip. If the DNA comes into contact with vesicles, its conformation changes. This alters the fluorescent signal, because the distance between the fluorescent label and a second fluorescent molecule on the origami structure changes. This method allows vesicles to be detected.