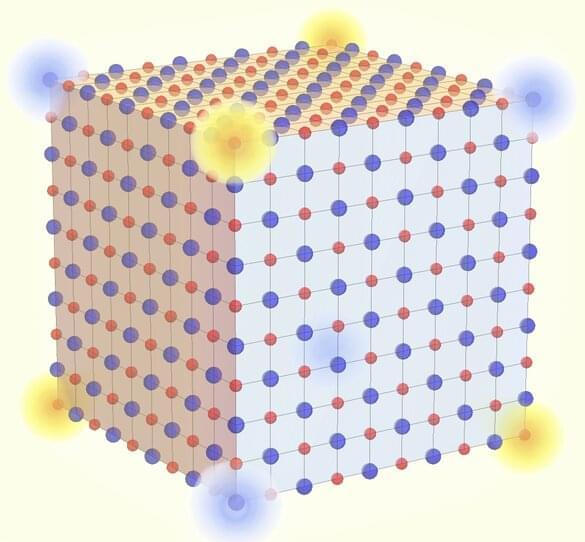

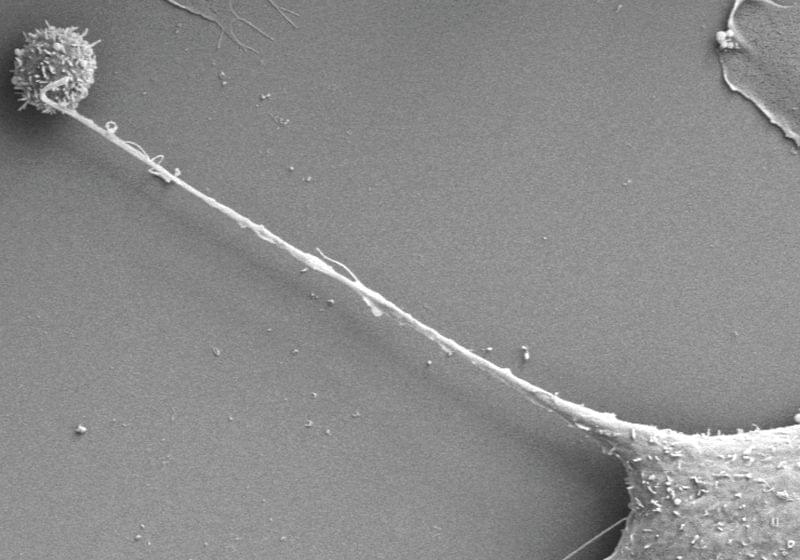

A joint research team from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) and the University of Tokyo discovered an unusual topological aspect of sodium chloride, commonly known as table salt, which will not only facilitate the understanding of the mechanism behind salt’s dissolution and formation, but may also pave the way for the future design of nanoscale conducting quantum wires.

There is a whole variety of advanced materials in our daily life, and many gadgets and technology are created through the assembly of different materials. Cellphones, for example, adopted a combination of many different substances—glass for the monitor, aluminum alloy for the frame, and metals like gold, silver and copper for their internal wiring. But nature has its own genius way of ‘cooking’ different properties into one wonder material, or what is known as ‘topological material’.

Topology, as a mathematical concept, studies what aspects of an object are robust under a smooth deformation. For instance, we can squeeze, stretch, or twist a T-shirt, but the number its openings would still be four so long as we do not tear it apart. The discovery of topological phases of matter, highlighted by the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physics, suggests that certain quantum materials are inherently a combination of electrical insulators and conductors. This could necessitate a conducting boundary even when the bulk of the material is insulating. Such materials are neither classified as a metal nor an insulator, but a natural assembly of the two.