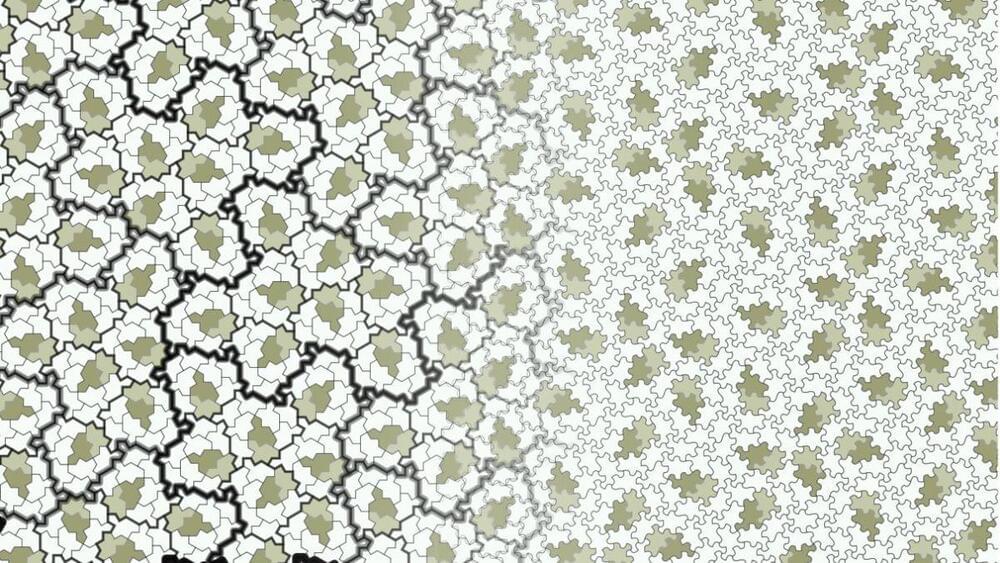

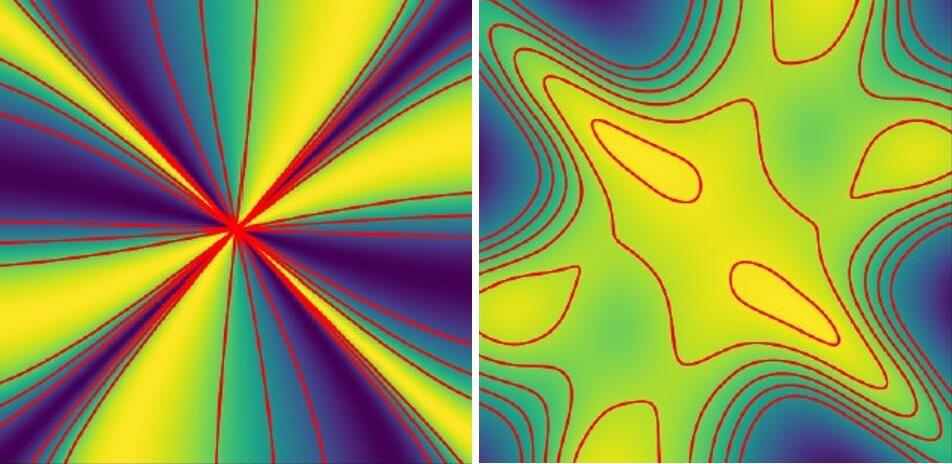

Researchers have discovered a new 14-sided shape called the Spectre that can be used to tile a surface without ever creating a repeating pattern, ending a decades’ long mathematical hunt.

General relativity, part of the wide-ranging physical theory of relativity formed by the German-born physicist Albert Einstein. It was conceived by Einstein in 1915. It explains gravity based on the way space can ‘curve’, or, to put it more accurately, it associates the force of gravity with the changing geometry of space-time. (Einstein’s gravity)

The mathematical equations of Einstein’s general theory of relativity, tested time and time again, are currently the most accurate way to predict gravitational interactions, replacing those developed by Isaac Newton several centuries prior.

Over the last century, many experiments have confirmed the validity of both special and general relativity. In the first major test of general relativity, astronomers in 1919 measured the deflection of light from distant stars as the starlight passed by our sun, proving that gravity does, in fact, distort or curve space.

Read it on : https://kllonusk.wordpress.com/2022/11/19/general-relativity…ed-simply/

@Klonusk.

Mail : [email protected].

#generalrelativity #gravity #relativity #general theory # General theory of relativity.

Joscha Bach is a cognitive scientist focusing on cognitive architectures, consciousness, models of mental representation, emotion, motivation and sociality.

Patreon: https://patreon.com/curtjaimungal.

Crypto: https://tinyurl.com/cryptoTOE

PayPal: https://tinyurl.com/paypalTOE

Twitter: https://twitter.com/TOEwithCurt.

Discord Invite: https://discord.com/invite/kBcnfNVwqs.

iTunes: https://podcasts.apple.com/ca/podcast/better-left-unsaid-wit…1521758802

Pandora: https://pdora.co/33b9lfP

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/4gL14b92xAErofYQA7bU4e.

Subreddit r/TheoriesOfEverything: https://reddit.com/r/theoriesofeverything.

Merch: https://tinyurl.com/TOEmerch.

0:00:00 Introduction.

0:00:17 Bach’s work ethic / daily routine.

0:01:35 What is your definition of truth?

0:04:41 Nature’s substratum is a “quantum graph”?

0:06:25 Mathematics as the descriptor of all language.

0:13:52 Why is constructivist mathematics “real”? What’s the definition of “real”?

0:17:06 What does it mean to “exist”? Does “pi” exist?

0:20:14 The mystery of something vs. nothing. Existence is the default.

0:21:11 Bach’s model vs. the multiverse.

0:26:51 Is the universe deterministic.

0:28:23 What determines the initial conditions, as well as the rules?

0:30:55 What is time? Is time fundamental?

0:34:21 What’s the optimal algorithm for finding truth?

0:40:40 Are the fundamental laws of physics ultimately “simple”?

0:50:17 The relationship between art and the artist’s cost function.

0:54:02 Ideas are stories, being directed by intuitions.

0:58:00 Society has a minimal role in training your intuitions.

0:59:24 Why does art benefit from a repressive government?

1:04:01 A market case for civil rights.

1:06:40 Fascism vs communism.

1:10:50 Bach’s “control / attention / reflective recall” model.

1:13:32 What’s more fundamental… Consciousness or attention?

1:16:02 The Chinese Room Experiment.

1:25:22 Is understanding predicated on consciousness?

1:26:22 Integrated Information Theory of consciousness (IIT)

1:30:15 Donald Hoffman’s theory of consciousness.

1:32:40 Douglas Hofstadter’s “strange loop” theory of consciousness.

1:34:10 Holonomic Brain theory of consciousness.

1:34:42 Daniel Dennett’s theory of consciousness.

1:36:57 Sensorimotor theory of consciousness (embodied cognition)

1:44:39 What is intelligence?

1:45:08 Intelligence vs. consciousness.

1:46:36 Where does Free Will come into play, in Bach’s model?

1:48:46 The opposite of free will can lead to, or feel like, addiction.

1:51:48 Changing your identity to effectively live forever.

1:59:13 Depersonalization disorder as a result of conceiving of your “self” as illusory.

2:02:25 Dealing with a fear of loss of control.

2:05:00 What about heart and conscience?

2:07:28 How to test / falsify Bach’s model of consciousness.

2:13:46 How has Bach’s model changed in the past few years?

2:14:41 Why Bach doesn’t practice Lucid Dreaming anymore.

2:15:33 Dreams and GAN’s (a machine learning framework)

2:18:08 If dreams are for helping us learn, why don’t we consciously remember our dreams.

2:19:58 Are dreams “real”? Is all of reality a dream?

2:20:39 How do you practically change your experience to be most positive / helpful?

2:23:56 What’s more important than survival? What’s worth dying for?

2:28:27 Bach’s identity.

2:29:44 Is there anything objectively wrong with hating humanity?

2:30:31 Practical Platonism.

2:33:00 What “God” is.

2:36:24 Gods are as real as you, Bach claims.

2:37:44 What “prayer” is, and why it works.

2:41:06 Our society has lost its future and thus our culture.

2:43:24 What does Bach disagree with Jordan Peterson about?

2:47:16 The millennials are the first generation that’s authoritarian since WW2

2:48:31 Bach’s views on the “social justice” movement.

2:51:29 Universal Basic Income as an answer to social inequality, or General Artificial Intelligence?

2:57:39 Nested hierarchy of “I“s (the conflicts within ourselves)

2:59:22 In the USA, innovation is “cheating” (for the most part)

3:02:27 Activists are usually operating on false information.

3:03:04 Bach’s Marxist roots and lessons to his former self.

3:08:45 BONUS BIT: On societies problems.

Subscribe if you want more conversations on Theories of Everything, Consciousness, Free Will, God, and the mathematics / physics of each.

I’m producing an imminent documentary Better Left Unsaid http://betterleftunsaidfilm.com on the topic of “when does the left go too far?” Visit that site if you’d like to contribute to getting the film distributed (in 2020) and seeing more conversations like this.

In a new landmark study, University of Minnesota research shows surprising links between human cognition and personality—pillars of human individuality that shape who we are and how we interact with the world. Personality influences our actions, emotions and thoughts, defining whether we are extroverted, polite, persistent, curious or anxious.

On the other hand, cognitive ability is the umbrella that reflects our capability for navigating complexity, such as articulating language, grasping intricate mathematics and drawing logical conclusions. Despite the prevailing belief that certain connections exist—for instance, introverted individuals are often perceived as more intelligent—scientists lacked a comprehensive understanding of these intricate connections.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, synthesizes data from over 1,300 studies from the past century, representing more than 2 million participants from 50 countries and integrating data from academic journals, test manuals, military databases, previously unpublished datasets and even proprietary databases of private companies.

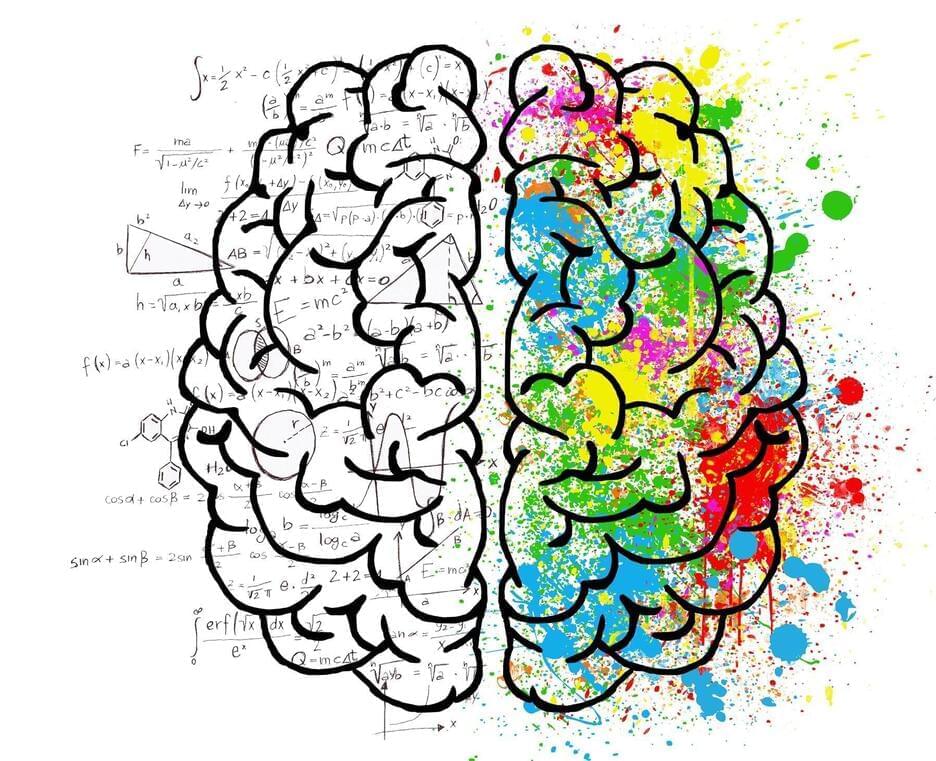

Perfect recall, computational wizardry and rapier wit: That’s the brain we all want, but how does one design such a brain? The real thing is comprised of ~80 billion neurons that coordinate with one another through tens of thousands of connections in the form of synapses. The human brain has no centralized processor, the way a standard laptop does.

Instead, many calculations are run in parallel, and outcomes are compared. While the operating principles of the human brain are not fully understood, existing mathematical algorithms can be used to rework deep learning principles into systems more like a human brain would. This brain-inspired computing paradigm—spiking neural networks (SNN)—provides a computing architecture well-aligned with the potential advantages of systems using both optical and electronic components.

In SNNs, information is processed in the form of spikes or action potentials, which are the electrical impulses that occur in real neurons when they fire. One of their key features is that they use asynchronous processing, meaning that spikes are processed as they occur in time, rather than being processed in a batch like in traditional neural networks. This allows SNNs to react quickly to changes in their inputs, and to perform certain types of computations more efficiently than traditional neural networks.

Paraconsistent logic challenges this standard view. A logical consequence relation is said to be paraconsistent if it is not explosive. Thus, if a consequence relation is paraconsistent, then even in circumstances where the available information is inconsistent, the consequence relation does not explode into triviality. Thus, paraconsistent logic accommodates inconsistency in a controlled way that treats inconsistent information as potentially informative.

The prefix ‘para’ in English has two meanings: ‘quasi’ (or ‘similar to, modelled on’) or ‘beyond’. When the term ‘paraconsistent’ was coined by Miró Quesada at the Third Latin America Conference on Mathematical Logic in 1976, he seems to have had the first meaning in mind. Many paraconsistent logicians, however, have taken it to mean the second, which provided different reasons for the development of paraconsistent logic as we will see below.

Paraconsistent logic is defined negatively: any logic is paraconsistent as long as it is not explosive. This means there is no single set of open problems or programs in paraconsistent logic. As such, this entry is not a complete survey of paraconsistent logic. The aim is to describe some philosophically salient features of a diverse field.

Excitations in solids can also be represented mathematically as quasiparticles; for example, lattice vibrations that increase with temperature can be well described as phonons. Mathematically, also quasiparticles can be described that have never been observed in a material before. If such “theoretical” quasiparticles have interesting talents, then it is worth taking a closer look. Take fractons, for example.

Fractons are fractions of spin excitations and are not allowed to possess kinetic energy. As a consequence, they are completely stationary and immobile. This makes fractons new candidates for perfectly secure information storage. Especially since they can be moved under special conditions, namely piggyback on another quasiparticle.

“Fractons have emerged from a mathematical extension of quantum electrodynamics, in which electric fields are treated not as vectors but as tensors—completely detached from real materials,” explains Prof. Dr. Johannes Reuther, theoretical physicist at the Freie Universität Berlin and at HZB.

Perspective from a very-educated layman. Er, laywoman.

This is Hello, Computer, a series of interviews carried out in 2023 at a time when artificial intelligence appears to be going everywhere, all at once.

Sabine Hossenfelder is a German theoretical physicist, science communicator, author, musician, and YouTuber. She is the author of Lost in Math: How beauty leads physics astray, which explores the concept of elegance in fundamental physics and cosmology, and of Existential Physics: A scientist’s guide to life’s biggest questions.

Sabine has published more than 80 research papers in the foundations of physics, from cosmology to quantum foundations and particle physics. Her writing has appeared in Scientific American, Nautilus, The New York Times, and The Guardian.

Sabine also works as a freelance popular science writer and runs the YouTube channel Science Without the Gobbledygook, where she talks about recent scientific developments and debunks hype, and a separate YouTube channel for music she writes and records.

SABINE HOSSENFELDER: My name is Sabine Hossenfelder. I’m a physicist and Research Fellow at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies, and I have a book that’s called “Existential Physics: A Scientist’s Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions.”

NARRATOR: Why did you pursue a career in physics?

HOSSENFELDER: I originally studied mathematics, not physics, because I was broadly interested in the question how much can we describe about nature with mathematics? But mathematics is a really big field and I couldn’t make up my mind exactly what to study. And so I decided to focus on that part of mathematics that’s actually good to describe nature and that naturally led me to physics. I was generally trying to make sense of the world and I thought that human interactions, social systems are a pretty hopeless case. There’s no way I’ll ever make sense of them. But simple things like particles or maybe planets and moons, I might be able to work that out. In the foundations of physics, we work with a lot of mathematics and I know from my own experience that it’s really, really hard to learn. And so I think for a lot of people out there, the journal articles that we write in the foundations of physics are just incomprehensible.