The material with the highest-temperature superconductivity at ambient pressure has received less attention than its easier-to-prepare relatives—until now.

Almost 200 million people, including children, around the world have endometriosis, a chronic disease in which the lining of the uterus grows outside of the uterus. More severe symptoms, such as extreme pain and potentially infertility, can often be mitigated with early identification and treatment, but no single point-of-care diagnostic test for the disease exists despite the ease of access to the tissue directly implicated.

While Penn State Professor Dipanjan Pan said that the blood and tissue shed from the uterus each month is often overlooked—and even stigmatized by some—as medical waste, menstrual effluent could enable earlier, more accessible detection of biological markers to help diagnose this disease.

Pan and his group have developed a proof-of-concept device capable of detecting HMGB1, a protein implicated in endometriosis development and progression, in menstrual blood with 500% more sensitivity than existing laboratory approaches. The device, which looks and operates much like a pregnancy test in how it detects the protein, hinges on a novel technique to synthesize nanosheets made of the atomically thin 2D material borophene, according to Pan, the Dorothy Foehr Huck & J. Lloyd Huck Chair Professor in Nanomedicine and corresponding author of the study detailing the team’s work.

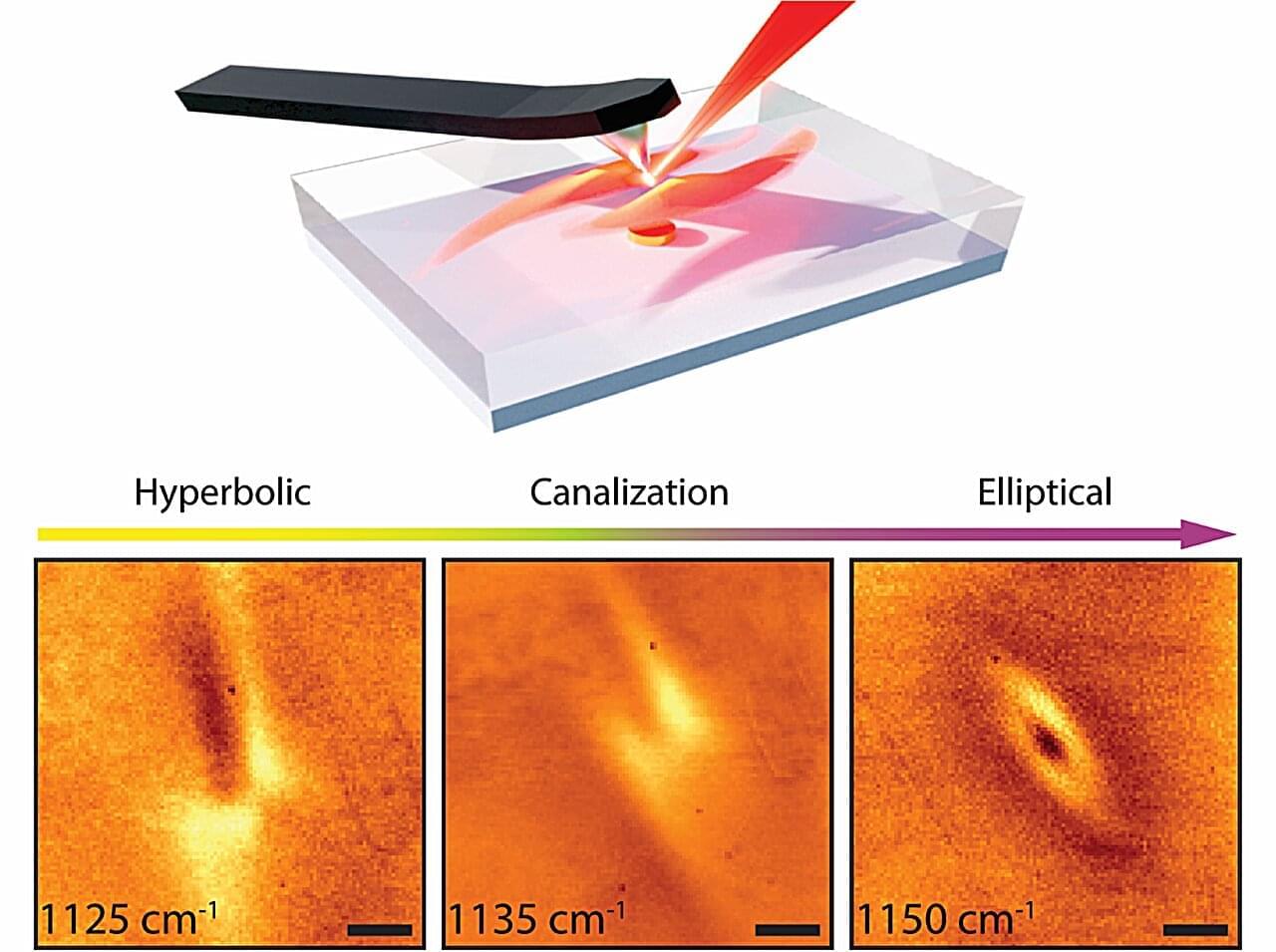

Monolithically integrated lasers on silicon photonics enable scalable, foundry-compatible production for data communications applications. However, material mismatches in heteroepitaxial systems and high coupling losses pose challenges for III-V integration on silicon. We combine three techniques: recessed silicon pockets for III-V growth, two-step heteroepitaxy using both MOCVD and MBE, and a polymer facet gap-fill approach to develop O-band InAs quantum dot lasers monolithically integrated on silicon photonics chiplets. Lasers coupled to silicon ring resonators and silicon nitride distributed Bragg reflectors (DBR) demonstrate single-mode lasing with side-mode suppression ratio up to 32 dB. Devices lase at temperatures up to 105 °C with an extrapolated operational lifetime of 6.2 years at 35 °C.

In a cosmic first, scientists watched planet-forming materials begin to solidify around a newborn star, offering a peek into what our Solar System may have looked like at birth. It’s a stunning replay of planetary evolution, just 1300 light-years away.

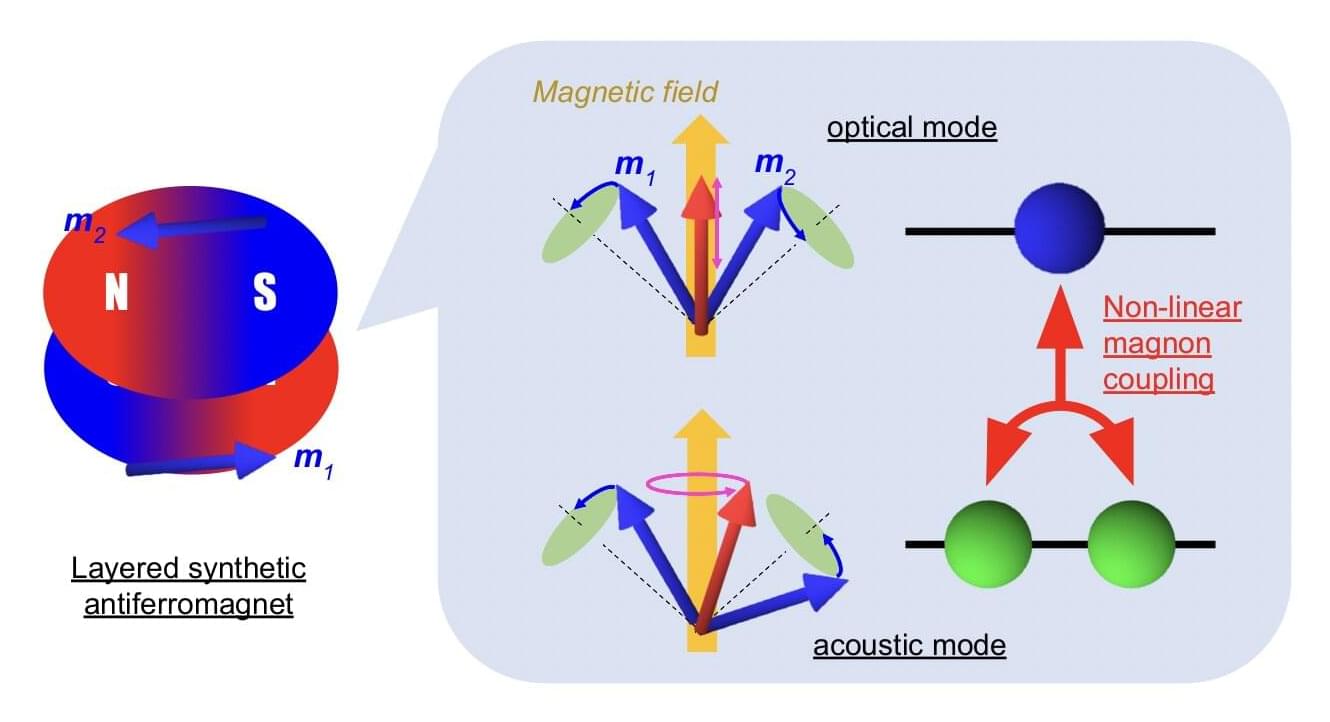

Synthetic antiferromagnets are carefully engineered magnetic materials made up of alternating ferromagnetic layers with oppositely aligned magnetic moments, separated by a non-magnetic spacer. These materials can display interesting magnetization patterns, characterized by swift changes in the behavior of magnetic moments in response to external forces, such as radio frequency (RF) currents.

When the magnetization of each layer in synthetic antiferromagnets is disturbed by an external force, its magnetic moments start to “precess,” or in other words, to rotate around their equilibrium direction. Past studies have identified two primary collective spin oscillation modes in synthetic antiferromagnets, influencing how magnetic moments precess.

The first is the acoustic mode, characterized by the synchronized rotation of ferromagnetic layers in the same direction and phase. The second is the optical mode, in which ferromagnetic layers rotate in opposite directions (i.e., with one layer’s magnetization tipping up and the other down).

As many in the field would agree, the growing interest in two-dimensional (2D) materials is not just a trend, it reflects real progress and curiosity. Materials like graphene and MoS2 have shown fascinating behaviour, particularly because they are atomically thin and yet still possess strong electrical, optical, and mechanical properties. These features make them promising candidates for new directions in electronics. That said, turning this promise into reliable technology is still a work in progress.

This Collection focuses on how 2D materials are being developed and used in integrated electronics. The emphasis is not only on device performance, but also on the actual process of bringing these materials into practical systems. From what I have seen, some of the most exciting results come from experiments where 2D materials are added into traditional semiconductor setups, whether that is in transistors, photodetectors, or memory elements. But challenges like scalability, environmental stability, and material quality remain real obstacles.

We’re interested in contributions across the board: device demonstrations, growth techniques, interface studies, or even theoretical modelling that can guide experimental designs. For instance, studies on how these materials interact with metal contacts, or how to reduce contact resistance, are very relevant here. So are efforts to pattern or align 2D layers over large areas, which is a challenge still not fully solved.

As soon as 2DMs are employed for devices, at some point they have to be grown or transferred onto insulators. A wide range of insulators has already been suggested for the use with 2DMs, starting with the amorphous 3D oxides known from Si technologies (SiO2, HfO2, Al2O3), and expanding to native 2D oxides (MoO3, WO3, Bi2SeO5), layered 2D crystals (hBN, mica) and 3D crystals like fluorides (CaF2, SrF2, MgF2) or perovskites (SrTiO3, BaTiO3). These insulators also contain various defects which can also be detrimental to device stability and reliability. Again, on the other hand, these defects can be exploited for added functionality like resistive switching devices, neuromorphic devices, and sensors.

Finally, 2DMs need to be contacted with metals, which typically introduces defects in the 2DMs which then have a strong impact on the behaviour of the resulting Schottky contacts as they tend to pin the Fermi-level and result in large series resistances.

This collection aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the latest research on defect characterization and control in 2D materials and devices. By bringing together studies that utilize advanced theoretical calculations, such as density functional theory (DFT) and first-principles calculations, as well as experimental techniques like transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning tunneling microscopy (STM), X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and various optical spectroscopies, this collection seeks to deepen our understanding of defect formation, propagation, control, and their impact on device performance.