Scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have demonstrated a potentially new way to make switches inside a computer’s processing chips, enabling them to use less energy and radiate less heat.

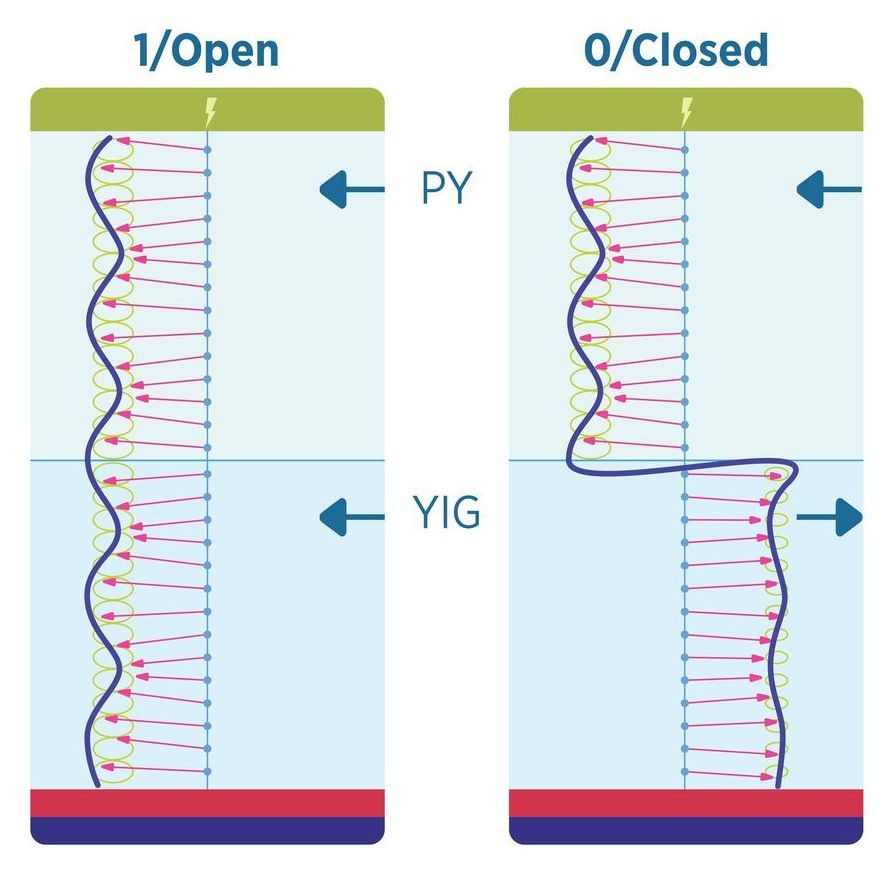

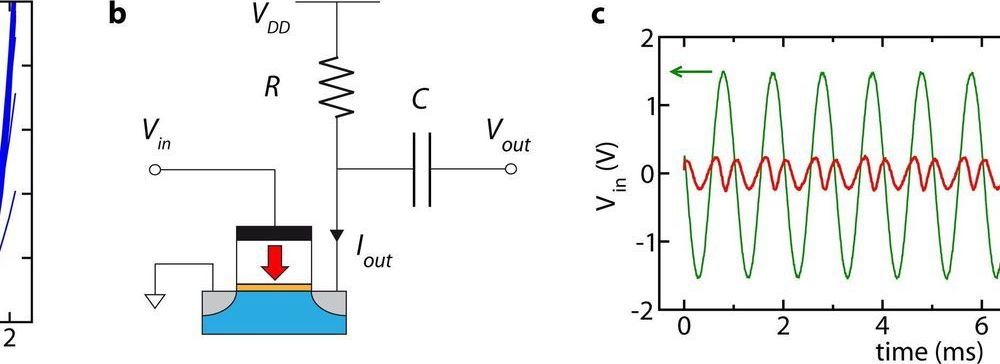

The team has developed a practical technique for controlling magnons, which are essentially waves that travel through magnetic materials and can carry information. To use magnons for information processing requires a switching mechanism that can control the transmission of a magnon signal through the device.

While other labs have created systems that carry and control magnons, the team’s approach brings two important firsts: Its elements can be built on silicon rather than exotic and expensive substrates, as other approaches have demanded. It also operates efficiently at room temperature, rather than requiring refrigeration. For these and other reasons, this new approach might be more readily employed by computer manufacturers.