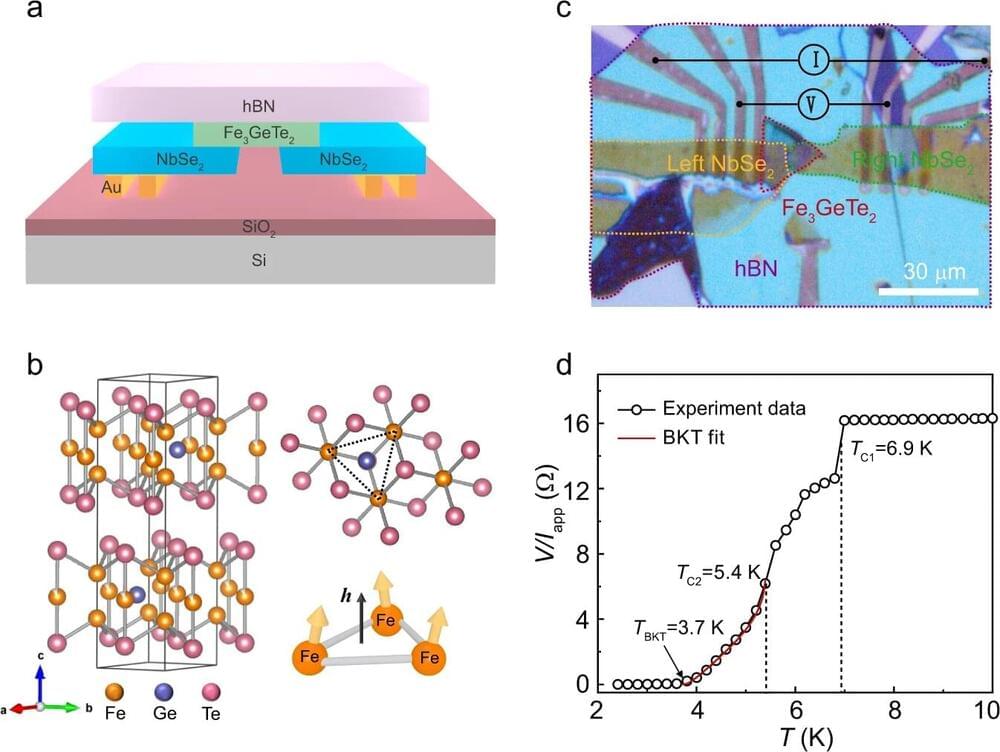

In a study published in Nature Communications, Prof. Xiang Bin’s group from University of Science and Technology of China of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with Assoc. Prof. Wang Zhi from Sun Yat-sen University, discovered the long-range skin Josephson supercurrent across a van der Waals ferromagnet.

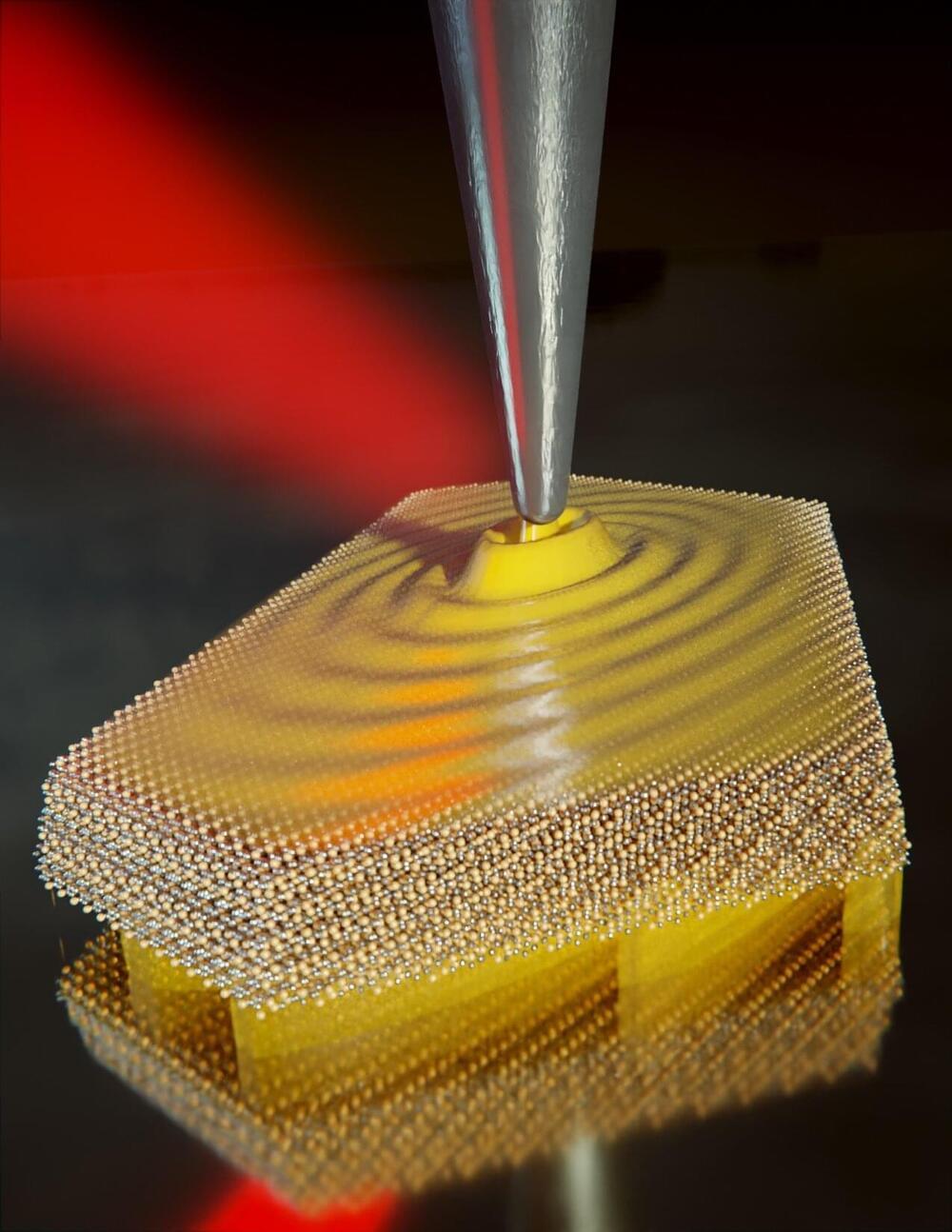

They bridged two spin-singlet superconductors NbSe2 (S) by constructing the van der Waals ferromagnet metal Fe3GeTe2 (F), and observed long-range supercurrent in the lateral Josephson junction (S/F/S) for the first time, which exhibits astonishing skin characteristics.

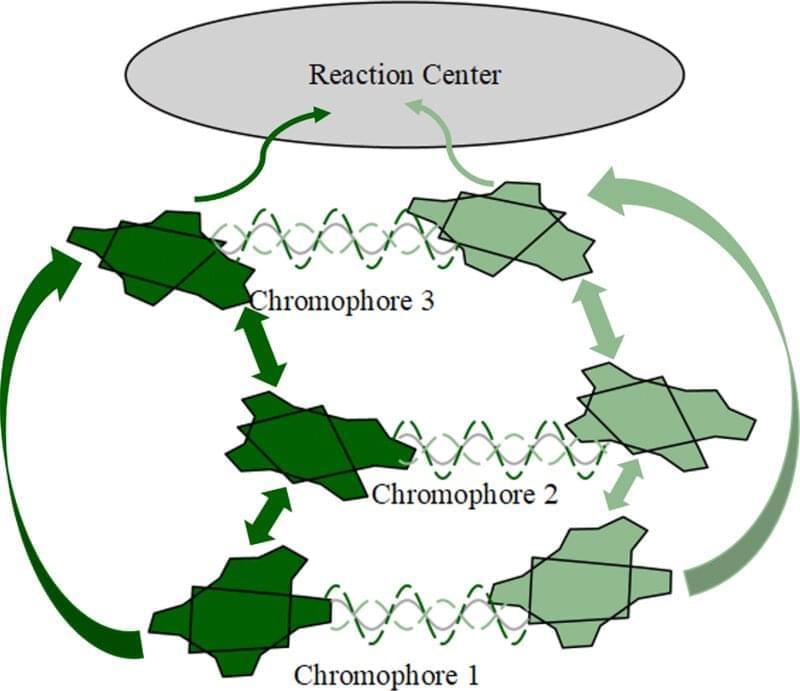

Ferromagnetism and superconductivity are two antagonistic macroscopic orderings. When the singlet supercurrent enters the ferromagnet, rapid decoherence of the Cooper pairs will be triggered.