PDF | The causal efficacy of a material system is usually thought to be produced by the law-like actions and interactions of its constituents. Here, a… | Find, read and cite all the research you need on ResearchGate.

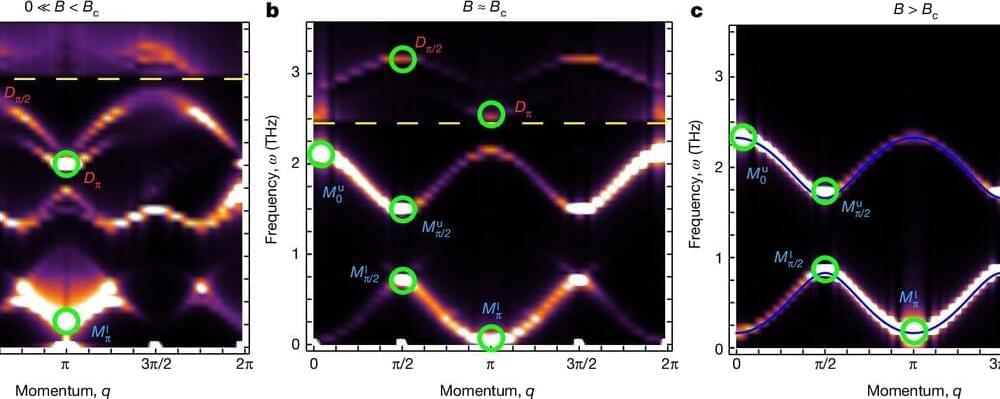

A group of physicists specialized in solid-state physics from the University of Cologne and international collaborators have examined crystals made from the material BaCO2V2O8 in the Cologne laboratory.

They discovered that the magnetic elementary excitations in the crystal are held together not only by attraction, but also by repulsive interactions. However, this results in a lower stability, making the observation of such repulsively bound states all the more surprising.

The results of the study, “Experimental observation of repulsively bound magnons,” are published in Nature.

Year 2016 face_with_colon_three

Clothing tears could be a thing of the past if a new material capable of “healing” itself after being ripped proves to be commercially viable.

Researchers at Pennsylvania State University created a fabric-coating technology derived from squid ring teeth that allows conventional textiles to self-repair.

“Fashion designers use natural fibers made of proteins like wool or silk that are expensive and they are not self-healing,” said Melik Demirel, a professor of engineering science and mechanics at Penn State. “We were looking for a way to make fabrics self-healing using conventional textiles. So we came up with this coating technology.”

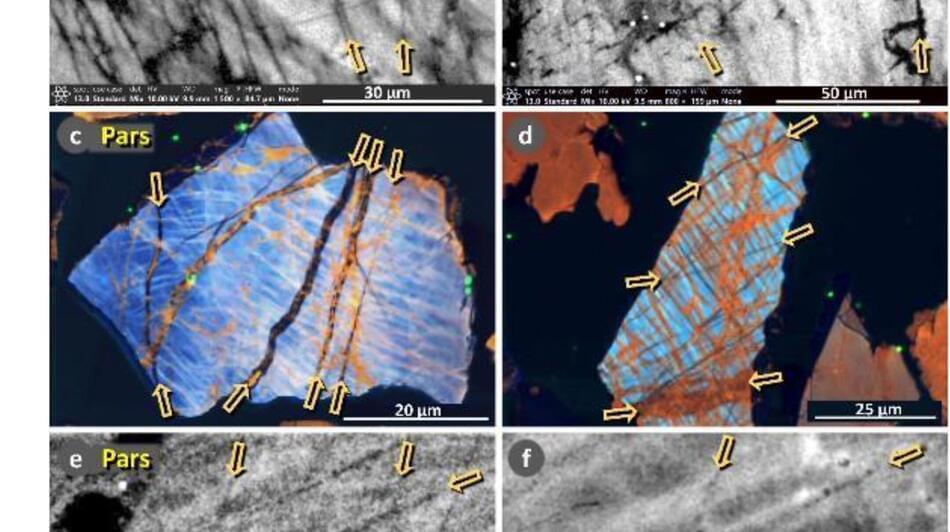

Researchers continue to expand the case for the Younger Dryas Impact hypothesis. The idea proposes that a fragmented comet smashed into the Earth’s atmosphere 12,800 years ago, causing a widespread climatic shift that, among other things, led to the abrupt reversal of the Earth’s warming trend and into an anomalous near-glacial period called the Younger Dryas.

Now, UC Santa Barbara emeritus professor James Kennett and colleagues report the presence of proxies associated with the cosmic airburst distributed over several separate sites in the eastern United States (New Jersey, Maryland and South Carolina), materials indicative of the force and temperature involved in such an event, including platinum, microspherules, meltglass and shock-fractured quartz. The study appears in the journal Airbursts and Cratering.

“What we’ve found is that the pressures and temperatures were not characteristic of major crater-forming impacts but were consistent with so-called ‘touchdown’ airbursts that don’t form much in the way of craters,” Kennett said.

In an effort to make them useless to poachers, researchers are implanting radioactive isotopes into the horns of rhinos in South Africa.

The unusual material would “render the horn useless… essentially poisonous for human consumption,” James Larkin, professor and dean of science at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, told Agence France-Presse.

The isotopes would also be “strong enough to set off detectors that are installed globally,” Larkin added, referring to hardware that was originally installed to “prevent nuclear terrorism.”

The team wondered if they could somehow leverage crystalline structures to identify a perfect candidate, sans building thousands of them in a lab.

The researchers were mostly on the lookout for 3D crystals with the right structural and electronic properties, so they could be “exfoliated.” 2D materials like graphene were extracted using this process from 3D.

However, this would be the first time researchers exfoliated one-dimensional materials like carbon nanotubes. This approach created a database of around 78,000 known 3D crystalline structures.