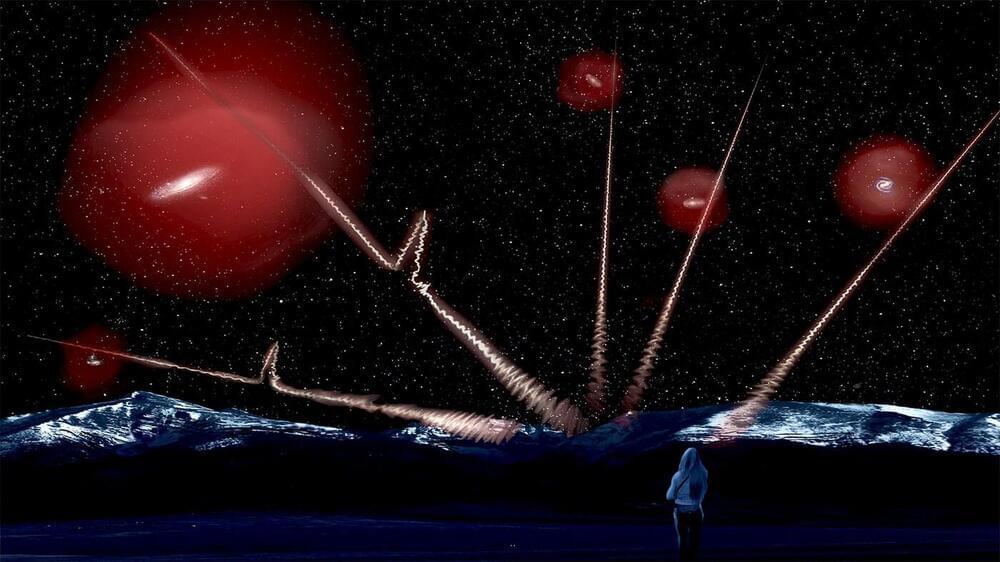

Powerful radio pulses originating deep in the cosmos can be used to study hidden pools of gas cocooning nearby galaxies, according to a new study appearing in the journal Nature Astronomy.

So-called fast radio bursts, or FRBs, are pulses of radio waves that typically originate millions to billions of light-years away (radio waves are electromagnetic radiation like the light we see with our eyes but have longer wavelengths and frequencies). The first FRB was discovered in 2007, and since then, hundreds more have been found. In 2020, Caltech’s STARE2 instrument (Survey for Transient Astronomical Radio Emission 2) and Canada’s CHIME (Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment) detected a massive FRB that went off in our own Milky Way galaxy. Those earlier results helped confirm the theory that the energetic events most likely originate from dead, magnetized stars called magnetars.

As more and more FRBs roll in, researchers are now asking how they can be used to study the gas that lies between us and the bursts. In particular, they would like to use the FRBs to probe halos of diffuse gas that surround galaxies. As the radio pulses travel toward Earth, the gas enveloping the galaxies is expected to slow the waves down and disperse the radio frequencies. In the new study, the researchers looked at a sample of 474 distant FRBs detected by CHIME, which has discovered the most FRBs to date, and showed that the subset of two dozen FRBs that passed through galactic halos were indeed slowed down more than non-intersecting FRBs.