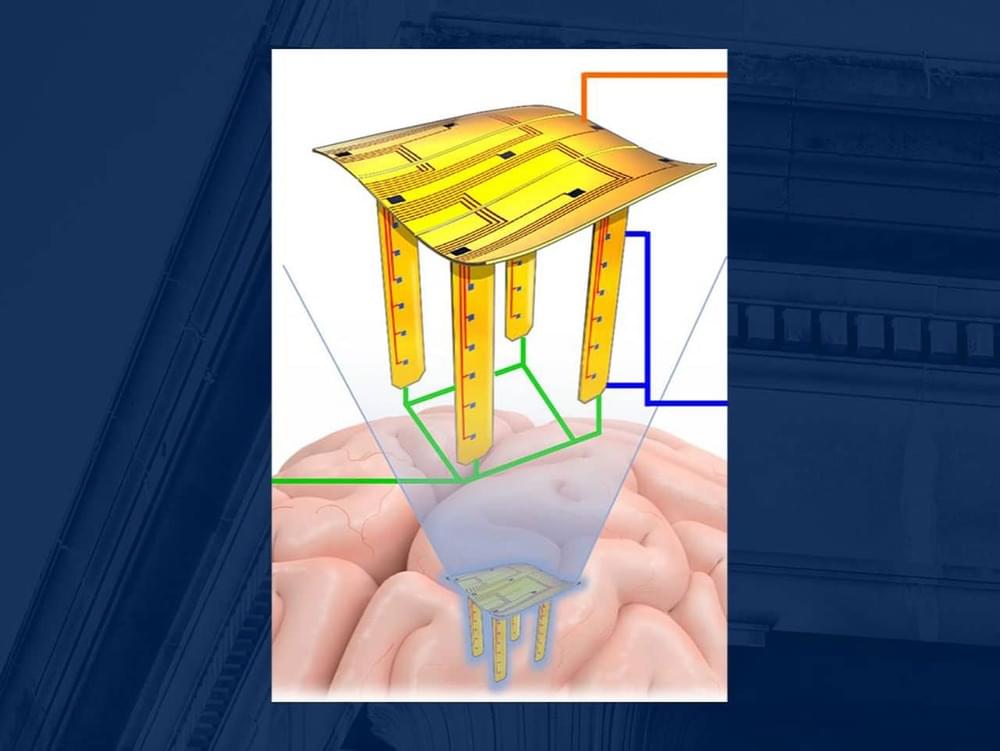

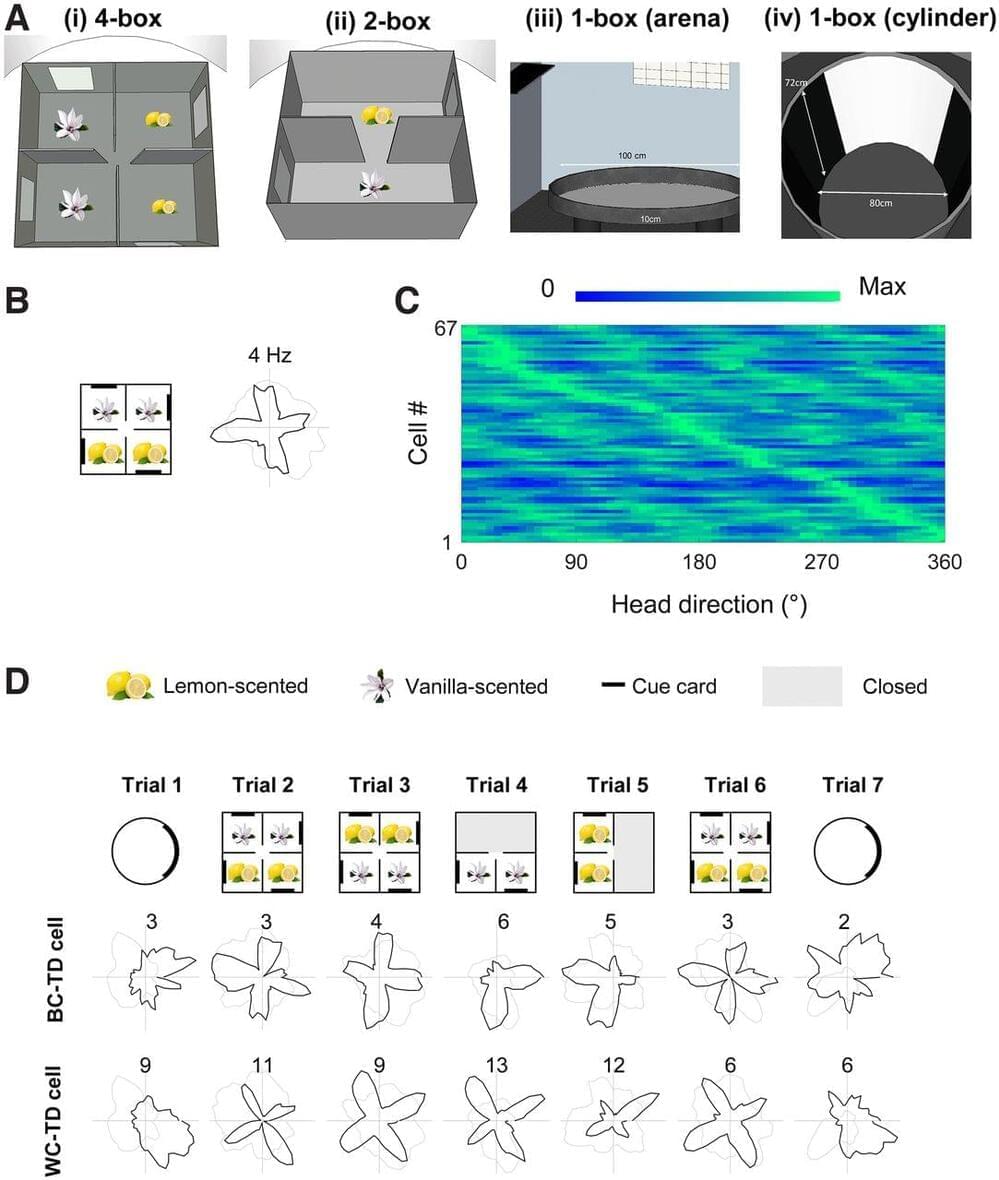

We investigated how environment symmetry shapes the neural processing of direction by recording directionally tuned retrosplenial neurons in male Lister hooded rats exploring multicompartment environments that had different levels of global rotational symmetry. Our hypothesis built on prior observations of twofold symmetry in the directional tuning curves of rats in a globally twofold-symmetric environment. To test whether environment symmetry was the relevant factor shaping the directional responses, here we deployed the same apparatus (two connected rectangular boxes) plus one with fourfold symmetry (a 2 × 2 array of connected square boxes) and one with onefold symmetry (a circular open-field arena). Consistent with our hypothesis we found many neurons with tuning curve symmetries that mirrored these environment symmetries, having twofold, fourfold, or onefold symmetric tuning, respectively. Some cells expressed this pattern only globally (across the whole environment), maintaining singular tuning curves in each subcompartment. However, others also expressed it locally within each subcompartment. Because multidirectionality has not been reported in naive rats in single environmental compartments, this suggests an experience-dependent effect of global environment symmetry on local firing symmetry. An intermingled population of directional neurons were classic head direction cells with globally referenced directional tuning. These cells were electrophysiologically distinct, with narrower tuning curves and a burstier firing pattern. Thus, retrosplenial directional neurons can simultaneously encode overall head direction and local head direction (relative to compartment layout). Furthermore, they can learn about global environment symmetry and express this locally. This may be important for the encoding of environment structure beyond immediate perceptual reach.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT We investigated how environment symmetry shapes the neural code for space by recording directionally tuned neurons from the retrosplenial cortex of rats exploring single-or multicompartment environments having onefold, twofold, or fourfold rotational symmetry. We found that many cells expressed a symmetry in their head direction tuning curves that matched the corresponding global environment symmetry, indicating plasticity of their directional tuning. They were also electrophysiologically distinct from canonical head directional cells. Notably, following exploration of the global space, many multidirectionally tuned neurons encoded global environment symmetry, even in local subcompartments. Our results suggest that multidirectional head direction codes contribute to the cognitive mapping of the complex structure of multicompartmented spaces.