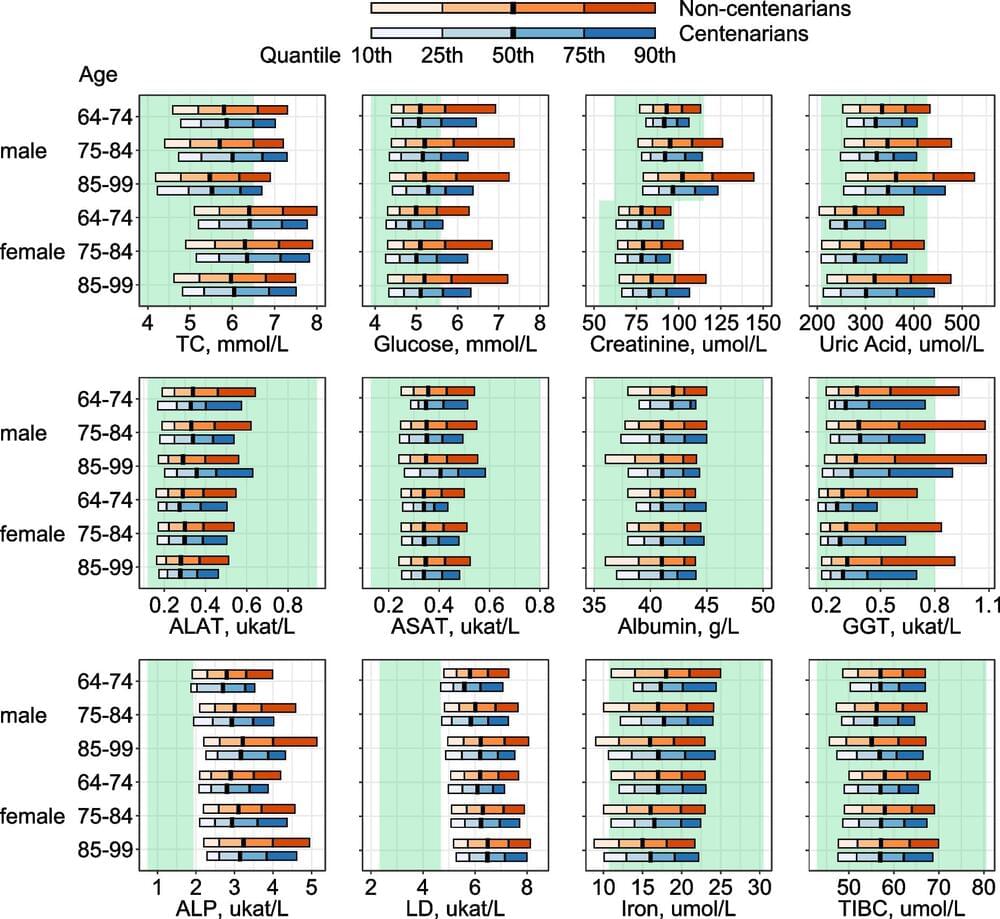

During aging, the human methylome undergoes both differential and variable shifts, accompanied by increased entropy. The distinction between variably methylated positions (VMPs) and differentially methylated positions (DMPs), their contribution to epigenetic age, and the role of cell type heterogeneity remain unclear.

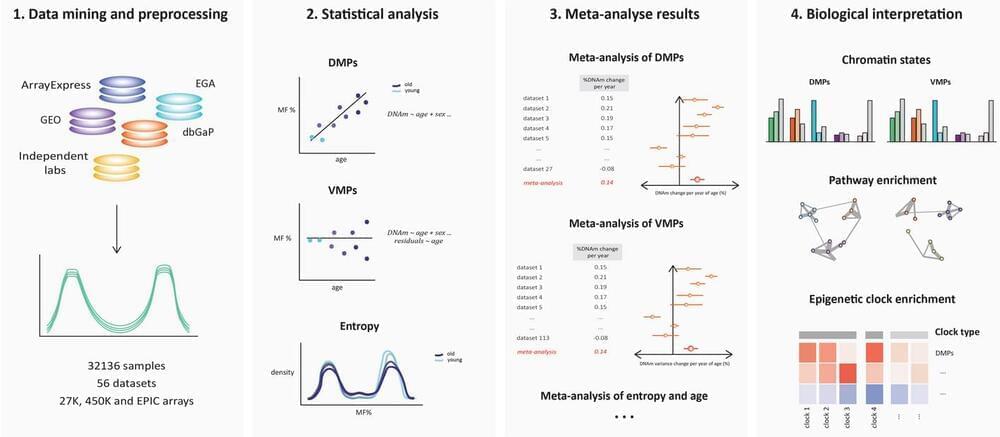

We conduct a comprehensive analysis of 32,000 human blood methylomes from 56 datasets (age range = 6–101 years). We find a significant proportion of the blood methylome that is differentially methylated with age (48% DMPs; FDR 0.005) and variably methylated with age (37% VMPs; FDR 0.005), with considerable overlap between the two groups (59% of DMPs are VMPs). Bivalent and Polycomb regions become increasingly methylated and divergent between individuals, while quiescent regions lose methylation more uniformly. Both chronological and biological clocks, but not pace-of-aging clocks, show a strong enrichment for CpGs undergoing both mean and variance changes during aging. The accumulation of DMPs shifting towards a methylation fraction of 50% drives the increase in entropy, smoothening the epigenetic landscape. However, approximately a quarter of DMPs exhibit anti-entropic effects, opposing this direction of change.