The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a global impact on all aspects of health care, including surgical procedures. For urologists, it has affected and will continue to influence how we approach the care of patients preoperatively, intraoperatively, and postoperatively. A risk-benefit assessment of each patient undergoing surgery should be performed during the COVID-19 pandemic based on the urgency of the surgery and the risk of viral illness and transmission. Patients with advanced age and comorbidities have a higher incidence of mortality. Routine preoperative testing and symptom screening is recommended to identify those with COVID-19. Adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) for the surgical team is essential to protect health care workers and ensure an adequate workforce. For COVID-19 positive or suspected patients, the use of N95 respirators is recommended if available. The anesthesia method chosen should attempt to minimize aerosolization of the virus. Negative pressure rooms are strongly preferred for intubation/extubation and other aerosolizing procedures for COVID-19 positive patients or when COVID status is unknown. Although transmission has not yet been shown during laparoscopic and robotic procedures, efforts should be made to minimize the risk of aerosolization. Ultra-low particulate air filters are recommended for use during minimally invasive procedures to decrease the risk of viral transmission. Thorough cleaning and sterilization should be performed postoperatively with adequate time allowed for the operating room air to be cycled after procedures. COVID-19 patients should be separated from noninfected patients at all levels of care, including recovery, to decrease the risk of infection. Future directions will be guided by outcomes and infection rates as social distancing guidelines are relaxed and more surgical procedures are reintroduced. Recommendations should be adapted to the local environment and will continue to evolve as more data become available, the shortage of testing and PPE is resolved, and a vaccine and therapeutics for COVID-19 are developed.

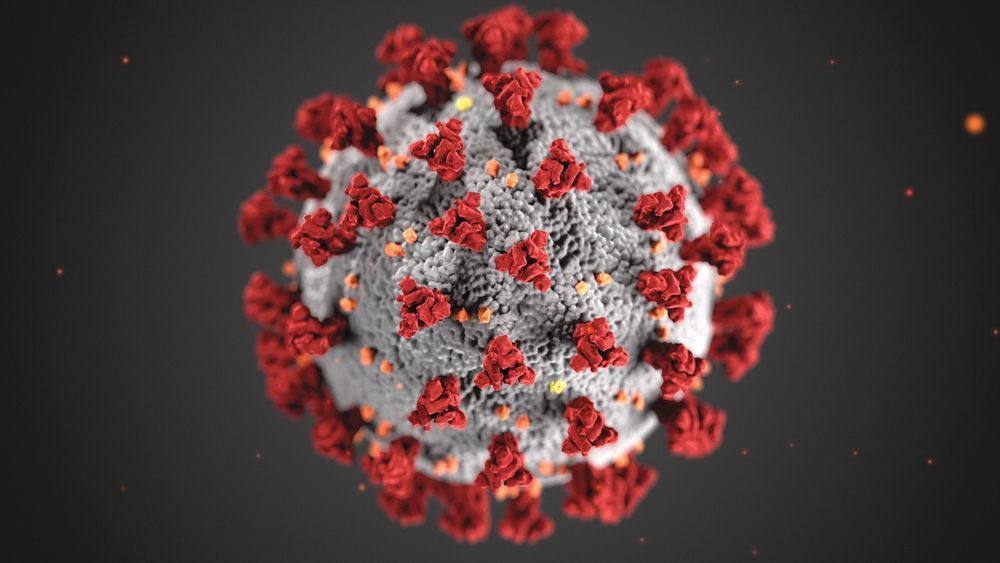

The first reported cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), originated in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China in December 2019. This respiratory disease spread outside of China, leading to outbreaks in Korea, Iran, Italy, and, eventually, the United States and the rest of the world. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak to be a pandemic. At the time of this writing, there are currently more than 1.3 million confirmed cases worldwide, with the total deaths numbering more than 74,000.1 This pandemic is unlike anything that has been seen in recent history.

From a urologic surgery perspective, many questions arise regarding the immediate and long-term care of our patients. The goal of this article is to summarize some of the current information available on preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care. As we gain more knowledge about how the virus behaves, this body of literature will inevitably change.