A research team has unveiled a crucial mechanism that helps regulate DNA damage repair, with important implications for improving cancer treatment outcomes.

The result was published in Cell Death & Differentiation. The team was led by Professor Zhao Guoping at the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

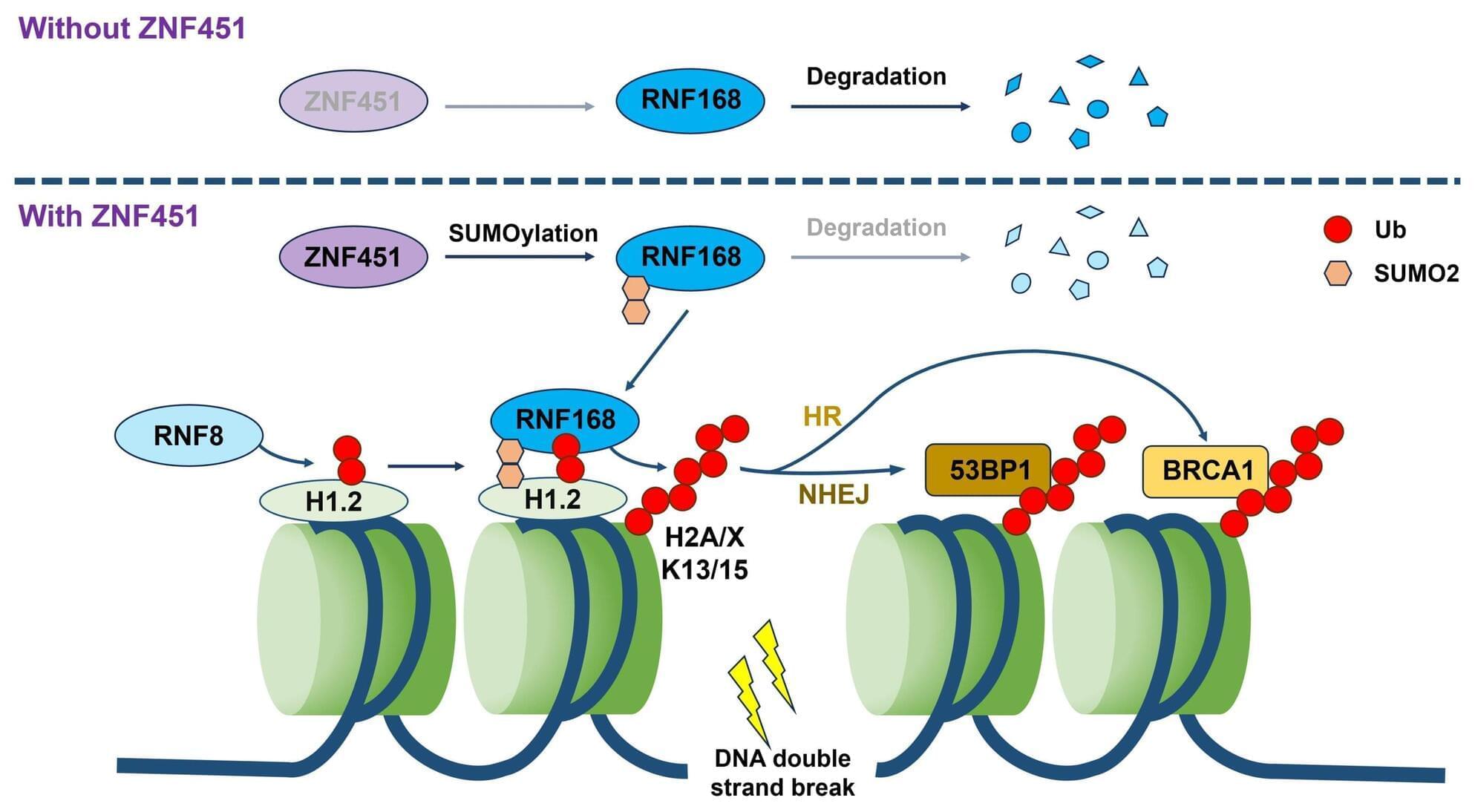

The efficacy of radiotherapy is largely limited by the DNA damage repair capacity of tumor cells. When ionizing radiation induces DNA double-strand breaks—the primary lethal damage—tumor cells often exhibit abnormal overexpression of DNA repair proteins, establishing a robust damage response system that drives clinical radioresistance. To address this challenge, the team deciphered the regulatory network of epigenetic modifications in DNA damage repair.