We could modify plants to grow in a day with the genetic dna mechanisms we find in bamboo.

Bamboo plant.

Proteins can communicate through DNA, conducting a long-distance dialogue that serves as a kind of genetic “switch,” according to Weizmann Institute of Science researchers. They found that the binding of proteins to one site of a DNA molecule can physically affect another binding site at a distant location, and that this “peer effect” activates certain genes. This effect had previously been observed in artificial systems, but the Weizmann study is the first to show it takes place in the DNA of living organisms.

A team headed by Dr. Hagen Hofmann of the Chemical and Structural Biology Department made this discovery while studying a peculiar phenomenon in the soil bacteria Bacillus subtilis. A small minority of these bacteria demonstrate a unique skill: an ability to enrich their genomes by taking up bacterial gene segments scattered in the soil around them. This ability depends on a protein called ComK, a transcription factor, which binds to the DNA to activate the genes that make the scavenging possible. However, it was unknown how exactly this activation works.

Because the brain responses in children with different forms of autism overlapped, future therapies that are effective for Phelan-McDermid syndrome could potentially help other autistic children with similar neural patterns, Siper says.

Brain responses to visual stimuli are smaller and weaker in children with Phelan-McDermid syndrome, an autism-linked genetic condition, than in non-autistic children, according to a new study. The difference in response is greater in children with larger genetic mutations.

Mutations or deletions in SHANK3, one of the genes most strongly linked to autism, cause Phelan-McDermid syndrome. More than 80 percent of people with the condition have autism; they also often have intellectual disability, developmental delays and other medical issues, though these traits and their severity can vary widely.

The new study is the first to use electroencephalography (EEG) to measure visual evoked potentials — brain responses that occur shortly after a person views a visual stimulus — in people with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. The team previously identified differences in these responses in people with ‘idiopathic’ autism, or autism with no known genetic cause. Other researchers have linked atypical visual evoked potentials to other single-gene causes of autism, such as Rett syndrome.

The human body can be genetically inclined to attack its own cells, destroying the beta cells in the pancreas that make insulin, which helps convert sugar into energy. Called Type 1 diabetes, this disorder can occur at any age and can be fatal if not carefully managed with insulin shots or an insulin pump to balance the body’s sugar levels.

But there may be another, personalized option on the horizon, according to Xiaojun “Lance” Lian, associate professor of biomedical engineering and biology at Penn State. For the first time, Lian and his team converted human embryonic stem cells into beta cells capable of producing insulin using only small molecules in the laboratory, making the process more efficient and cost-effective.

Stem cells can become other cell types through signals in their environment, and some mature cells can revert to stem cells—induced pluripotency. The researchers found that their approach worked for human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells, both derived from federally approved stem cell lines. According to Lian, the effectiveness of their approach could reduce or eliminate the need for human embryonic stem cells in future work. They published their results today (Aug. 26) in Stem Cell Reports.

In the fictional links he drew between immortal vampires and bats, Dracula creator Bram Stoker may have had one thing right.

“Maybe it’s all in the blood,” says Emma Teeling, a geneticist studying the exceptional longevity of bats in the hope of discovering benefits for humans.

The University College Dublin researcher works with the charity Bretagne Vivante to study bats living in rural churches and schools in Brittany, western France.

Studying Novel Plasma Fractions For Age-Related Diseases And Systemic Rejuvenation — Dr. Harold Katcher Ph.D., Chief Scientific Officer, Yuvan Research Inc.

Dr. Harold Katcher is the Chief Scientific Officer at Yuvan Research Inc., a biotech company exploring the development of novel, young plasma fraction rejuvenation treatments in mammals.

Most recently Dr. Katcher was the Academic Director for Natural Sciences for the Asian Division of the University of Maryland Global Campus and throughout his career, Dr. Katcher has been a pioneer in the field of cancer research, and in the development of modern aspects of gene hunting and sequencing (including as one of the discoverers of the breast cancer gene BRCA1) as part of Myriad Genetics, and carries expertise in bioinformatics, chronobiology, and biotechnology.

Dr. Katcher has thousands of citations in the scientific literature, with publications ranging from protein structure to bacteriology, biotechnology, bioinformatics and biochemistry.

Dr. Katcher is launching his new book “The Illusion of Knowledge” on September 4th, 2021.

Okay, maybe not as big as the one in the picture.

Potatoes are my favorite vegetable; you can turn them into fries, bake them for an exquisite dish or mash them and eat them as a side dish. There are endless possibilities to cook a potato and what can be better than adding human fat gene in them to make them bigger and juicier?

Scientists have been experimenting with growing larger crops and it seems like they found the perfect solution; adding the human gene related to obesity and fat mass into the plants to yield super crops. The potato plants were inserted with a fat-regulating protein called FTO which changed the genetic code into producing extra proteins which resulted in large potatoes that were almost twice the size of regular ones grown from the same plant crop. “It [was] really a bold and bizarre idea. To be honest, we were probably expecting some catastrophic effects,” said Chuan He, a chemist at University of Chicago.

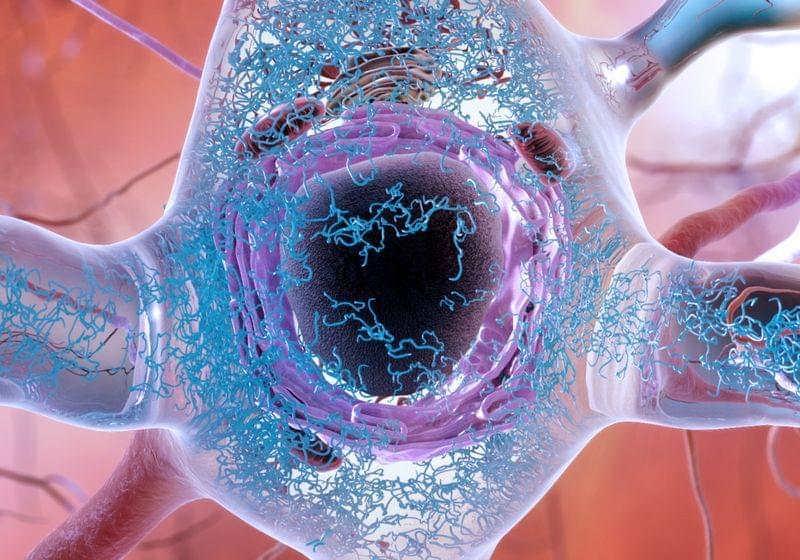

ABOVE: MAPT, one of the genes linked to both heavy drinking and neurodegenerative diseases, codes for the protein tau (blue in this illustration) inside a neuron. NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON AGING/ NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

Some genetic risk factors for alcohol use disorder overlap with those for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, scientists reported in Nature Communications on August 20. The study, which relied on a combination of genetic, transcriptomic, and epigenetic data, also offers insight into the molecular commonalities among these disorders, and their connections to immune disfunction.

“By meshing findings from genome wide association studies… ith gene expression in brain and other tissues, this new study has prioritized genes likely to harbor regulatory variants influencing risk of Alcohol Use Disorder,” writes David Goldman, a neurogenetics researcher at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), in an email to The Scientist. “Several of these genes are also associated with neurodegenerative disorders—an intriguing connection because of alcohol’s ability to prematurely age the brain.”

A team at Penn’s medical school discovered that an epigenetic regulatory protein called ZMYND8 governs the expression of genes that are critical for the growth and survival of AML cells. Inhibiting ZMYND8 in mouse models shrank tumors. The researchers also found a biomarker that they believe could predict which patients are likely to respond to ZMYND8 inhibition, they reported in the journal Molecular Cell.

AML is one of the hardest leukemias to treat, with a five-year survival rate of about 27% in adults. The Penn team had been searching for precision medicine approaches that could improve the prognosis for adults with AML, and they turned to CRISPR for help.

ZMYND8 is known as a “histone reader” in cancer that can recognize epigenetic changes and influence gene expression involved in metastasis.

What we’ll soon see is the ultimate self-directed evolution fueled forward by gene editing, genetic engineering, reproduction assisted technology, neuro-engineering, mind uploading and creation of artificial life. Our success as a technological species essentially created what might be called our species-specific “success formula.” We devised tools and instruments, created new methodologies and processes, and readjusted ecological niches to suit our needs. And our technology shaped us back by shaping our minds. In a very real sense, we have co-evolved with our technology. As an animal species among many other species competing for survival, this was our unique passage to success.

#TECHNOCULTURE : #TheRiseofMan #CyberneticTheoryofMind

Technology has always been a “double-edged sword” since fire, which has kept us warm and cooked our food but also burned down our huts. Today, we surely enjoy the fruits of modern civilization when we fly halfway around the globe on an airbus, when we extend our mental functionality with a whole array of Internet-enabled devices, when our cities and dwellings become icons of technological sophistication.