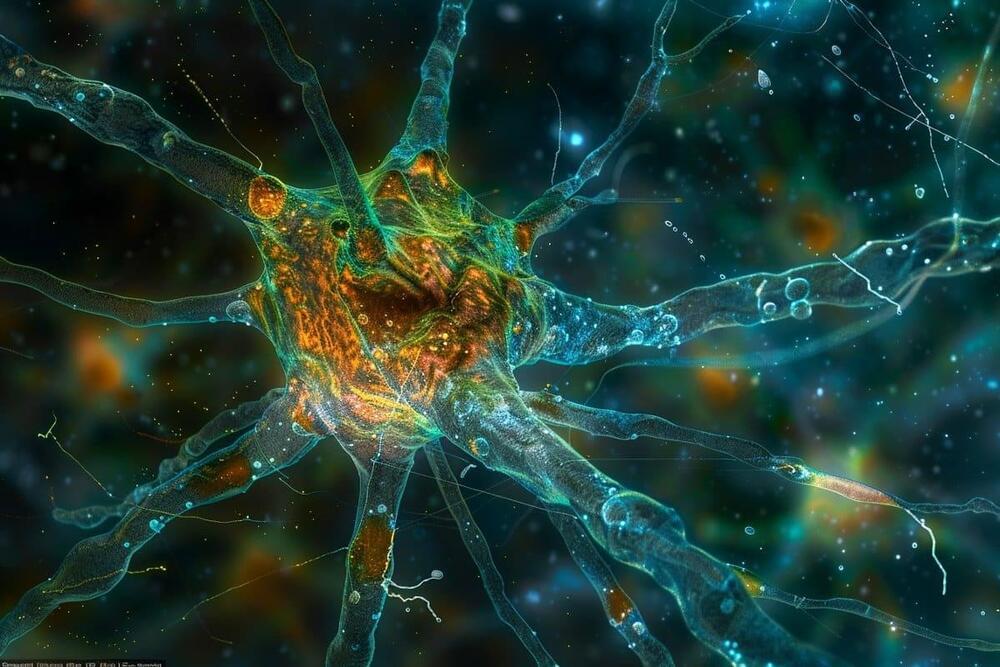

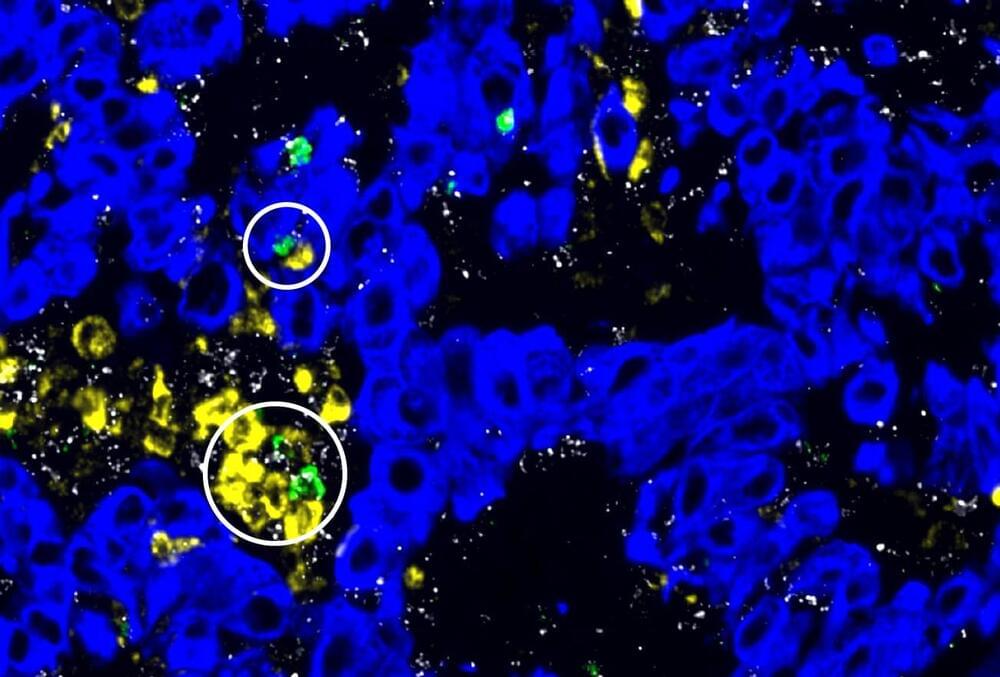

Results of DNA studies also seem to confirm the idea that optimism is an effective tool for slowing down cellular aging, of which telomere shortening is a biomarker. (Telomeres are the protective caps at the end of our chromosomes.) This research is still in progress, but the early results are informative. In 2012, Elizabeth Blackburn, who three years earlier shared a Nobel Prize for her work in discovering the enzyme that replenishes the telomere, and Elissa Epel at the University of California at San Francisco, in collaboration with other institutions, identified a correlation between pessimism and accelerated telomere shortening in a group of postmenopausal women. A pessimistic attitude, they found, may indeed be associated with shorter telomeres. Studies are moving toward larger sample sizes, but it already seems apparent that optimism and pessimism play a significant role in our health as well as in the rate of cellular senescence. More recently, in 2021, Harvard University scientists, in collaboration with Boston University and the Ospedale Maggiore in Milan, Italy, observed the telomeres of 490 elderly men in the Normative Health Study on U.S. veterans. Subjects with strongly pessimistic attitudes were associated with shorter telomeres — a further encouraging finding in the study of those mechanisms that make optimism and pessimism biologically relevant.

Optimism is thought to be genetically determined for only 25 percent of the population. For the rest, it’s the result of our social relationships or deliberate efforts to learn more positive thinking. In an interview with Jane Brody for the New York Times, Rozanski explained that “our way of thinking is habitual, unaware, so the first step is to learn to control ourselves when negative thoughts assail us and commit ourselves to change the way we look at things. We must recognize that our way of thinking is not necessarily the only way of looking at a situation. This thought alone can lower the toxic effect of negativity.” For Rozanski, optimism, like a muscle, can be trained to become stronger through positivity and gratitude, in order to replace an irrational negative thought with a positive and more reasonable one.

While the exact mechanisms remain under investigation, a growing body of research suggests that optimism plays a significant role in promoting both physical and mental well-being. Cultivating a positive outlook, then, can be a powerful tool for fostering resilience, managing stress, and potentially even enhancing longevity. By adopting practices that nurture optimism, we can empower ourselves to navigate life’s challenges with greater strength and live healthier, happier lives.