He Jiankui, who went to prison for three years for making the world’s first gene-edited babies, talked to MIT Technology Review about his new research plans.

Researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have traced the domestication of maize back to its origins 9,000 years ago, highlighting its crossbreeding with teosinte mexicana for cold adaptability.

The discovery of a genetic mechanism known as Teosinte Pollen Drive by Professor Rob Martienssen provides a critical link in understanding maize’s rapid adaptation and distribution across America, shedding light on evolutionary processes and potential agricultural applications.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) scientists have begun to unravel a mystery millennia in the making. Our story begins 9,000 years ago. It was then that maize was first domesticated in the Mexican lowlands. Some 5,000 years later, the crop crossed with a species from the Mexican highlands called teosinte mexicana. This resulted in cold adaptability. From here, corn spread across the continent, giving rise to the vegetable that is now such a big part of our diets. But how did it adapt so quickly? What biological mechanisms allowed the highland crop’s traits to take hold? Today, a potential answer emerges.

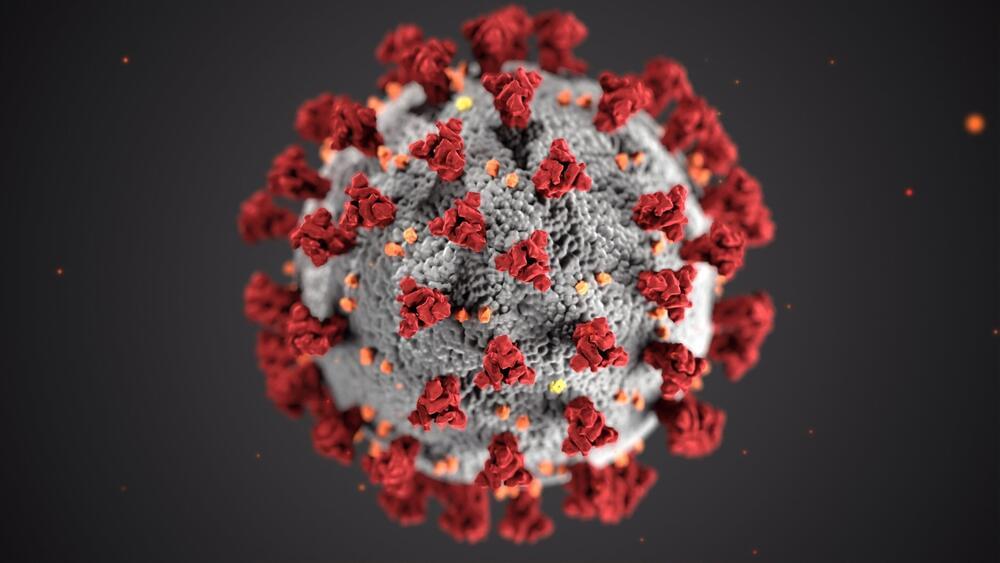

Building upon groundbreaking research demonstrating how the SARS-CoV-2 virus disrupts mitochondrial function in multiple organs, researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) demonstrated that mitochondrially-targeted antioxidants could reduce the effects of the virus while avoiding viral gene mutation resistance, a strategy that may be useful for treating other viruses.

The preclinical findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Last year, a multi-institutional consortium of researchers found that the genes of the mitochondria, the energy producers of our cells, can be negatively impacted by the virus, leading to dysfunction in multiple organs beyond the lungs.

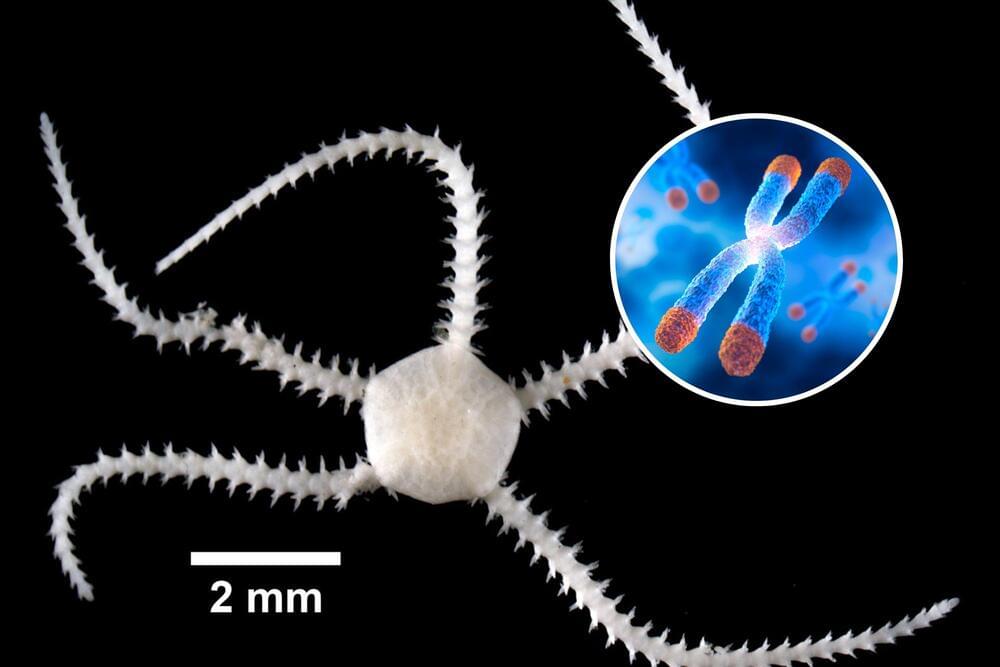

This is because the species undergoes a process called polyploidization, which is when a single chromosome is duplicated multiple times.

“It has amazing genetic diversity,” study co-author Tim O’Hara, a senior marine curator at Museums Victoria in Australia, told Newsweek.

“Instead of evolving into separate species over time, lineages readily hybridize with each other, so building up a great amount of genetic diversity. But not only that, they sometimes add their genomes together, so end up with four or more copies of each gene,” O’Hara said.

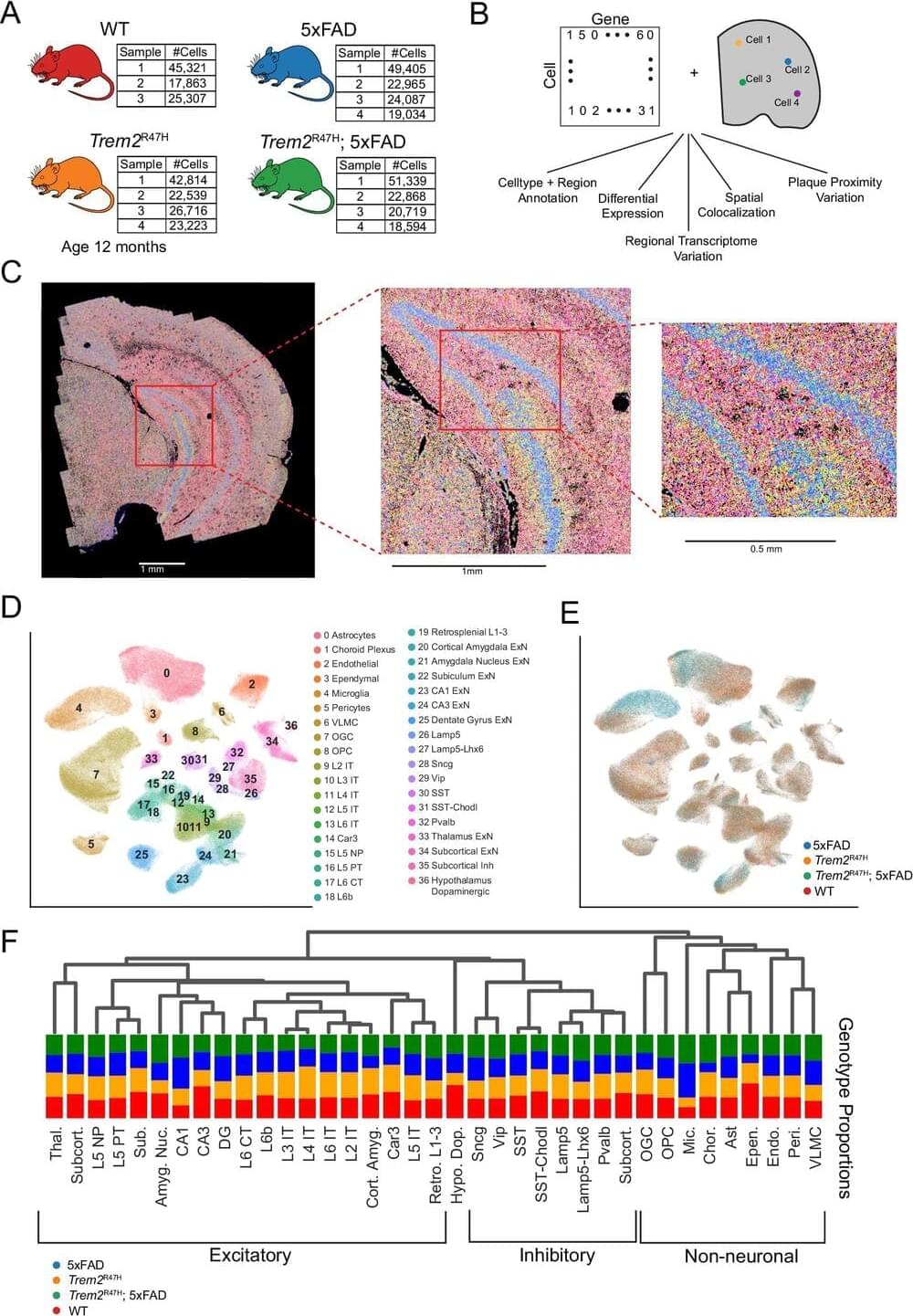

Researchers led by the University of California, Irvine have discovered how the TREM2 R47H genetic mutation causes certain brain areas to develop abnormal protein clumps, called beta-amyloid plaques, associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Leveraging single-cell Merfish spatial transcriptomics technology, the team was able to profile the effects of the mutation across multiple cortical and subcortical brain regions, offering first-of-their-kind insights at the single-cell level.

The study, published in Molecular Psychiatry, compared the brains of normal mice and special mouse models that undergo changes like those in humans with Alzheimer’s.

Findings revealed that the TREM2 mutation led to divergent patterns of beta-amyloid plaque accumulation in various parts of the brain involved in higher-level functions such as memory, reasoning and speech. It also affected certain cell types and their gene expression near the plaques.

Chromosomes are threadlike structures composed entirely of DNA that reside in the cells of all living things. Each one of these biological databanks contains a wealth of genetic information that scientists can use to glean insights into the history and evolution of life on Earth. Normally, the remains of dead creatures degrade over time, causing DNA to fragment. Most ancient animal DNA discovered to date has been incomplete, often comprised of fewer than 100 base pairs out of the billions that once made up the full sequence of the organism.

However, the 52,000-year-old skin sample at the heart of this research was taken from behind the ear of a mammoth discovered in Northern Siberia in 2018. An intensive analysis of the sample revealed the presence of complete fossil chromosomes. These chromosomes, each measuring billionths of a meter in length, had seemingly been frozen in a glass-like state for tens of thousands of years. Knowing the shape of an organism’s chromosomes can help researchers to assemble entire DNA sequences of extinct creatures, a task previously deemed nearly impossible due to DNA degradation over time.

“This is a new type of fossil, and its scale dwarfs that of individual ancient DNA fragments — a million times more sequence,” explained Erez Lieberman Aiden, a corresponding author on the study and director of the Center for Genome Architecture at the Baylor College of Medicine.

(THE CONVERSATION) Racism steals time from people’s lives – possibly because of the space it occupies in the mind.

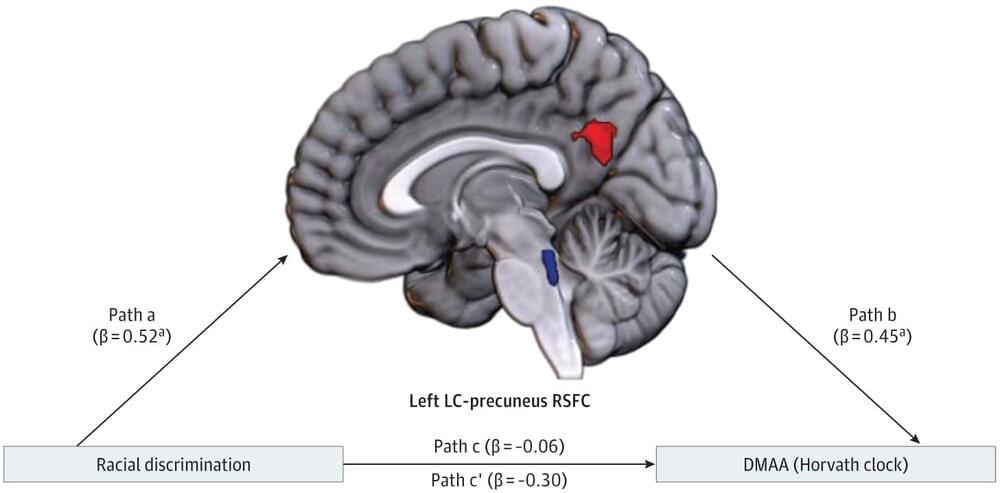

Question Is racial discrimination associated with brain connectivity, and are alterations in deep brain functional connectivity associated with accelerated epigenetic aging?

Findings In this cohort study of 90 Black women in the US, higher self-reported racial discrimination was associated with greater resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) between the locus coeruleus (LC) and precuneus. Significant indirect effects were observed for the association between racial discrimination frequency and DNA methylation age acceleration.

Meaning These findings suggest that racial discrimination is associated with greater connectivity in pathways involved with rumination, which may increase vulnerability to stress-related disorders and neurodegenerative disease via epigenetic age acceleration.

The ability to accurately quantify biological age could help monitor and control healthy aging. Epigenetic clocks have emerged as promising tools for estimating biological age, yet so far, most of these clocks have been developed from heterogeneous bulk tissues, and are thus composites of two aging processes, one reflecting the change of cell-type composition with age and another reflecting the aging of individual cell-types. There is thus a need to dissect and quantify these two components of epigenetic clocks, and to develop epigenetic clocks that can yield biological age estimates at cell-type resolution. Here we demonstrate that in blood and brain, approximately 35% of an epigenetic clock’s accuracy is driven by underlying shifts in lymphocyte and neuronal subsets, respectively. Using brain and liver tissue as prototypes, we build and validate neuron and hepatocyte specific DNA methylation clocks, and demonstrate that these cell-type specific clocks yield improved estimates of chronological age in the corresponding cell and tissue-types. We find that neuron and glia specific clocks display biological age acceleration in Alzheimer’s Disease with the effect being strongest for glia in the temporal lobe. The hepatocyte clock is found accelerated in liver under various pathological conditions. In contrast, non-cell-type specific clocks do not display biological age-acceleration, or only do so more marginally. In summary, this work highlights the importance of dissecting epigenetic clocks and quantifying biological age at cell-type resolution.

The authors have declared no competing interest.

The Illumina DNA methylation datasets analyzed here are all freely available from GEO (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).