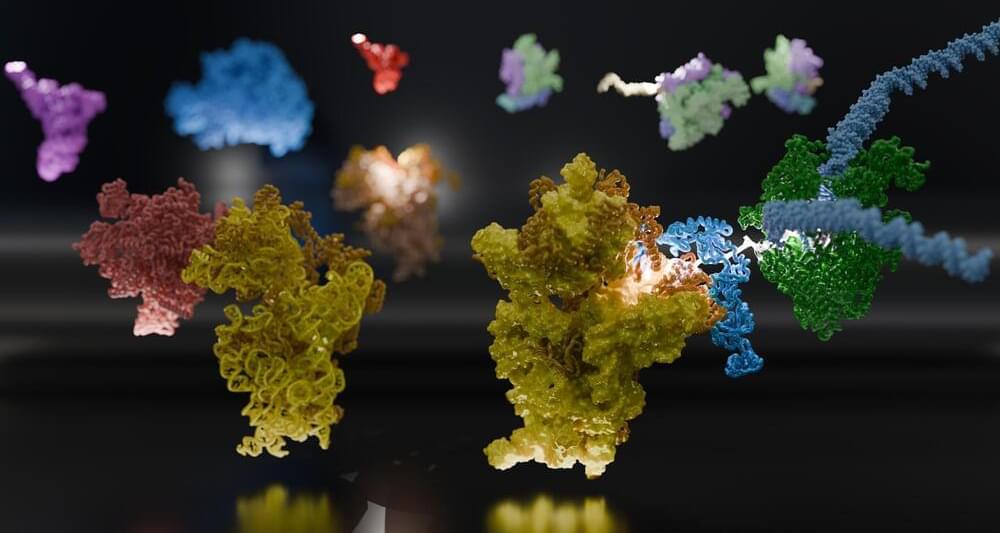

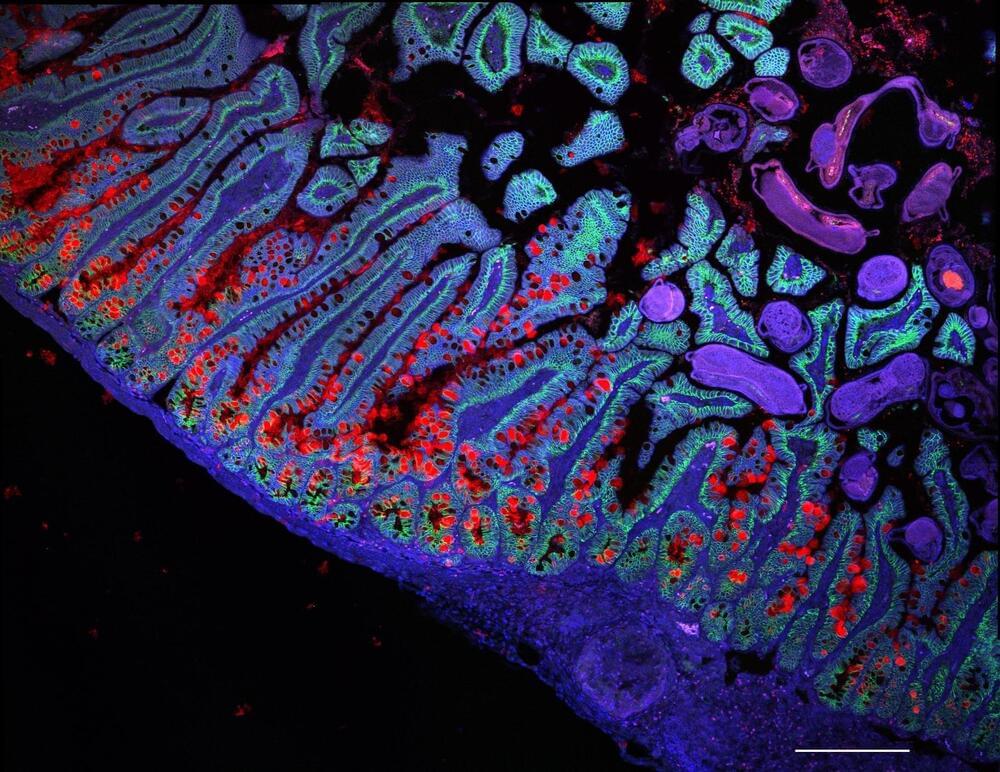

Within a cell, DNA carries the genetic code for building proteins. To build proteins, the cell makes a copy of DNA, called mRNA. Then, another molecule called a ribosome reads the mRNA, translating it into protein. But this step has been a visual mystery; scientists previously did not know how the ribosome attaches to and reads mRNA.

Now, a team of international scientists, including University of Michigan researchers, has used advanced microscopy to image how ribosomes recruit to mRNA while it’s being transcribed by an enzyme called RNA polymerase (RNAP). Their results, which examine the process in bacteria, are published in the journal Science.

“Understanding how the ribosome captures or ‘recruits’ the mRNA is a prerequisite for everything that comes after, such as understanding how it can even begin to interpret the information encoded in the mRNA,” said Albert Weixlbaumer, a researcher from Institut de génétique et de biologie moléculaire et cellulaire in France who co-led the study.