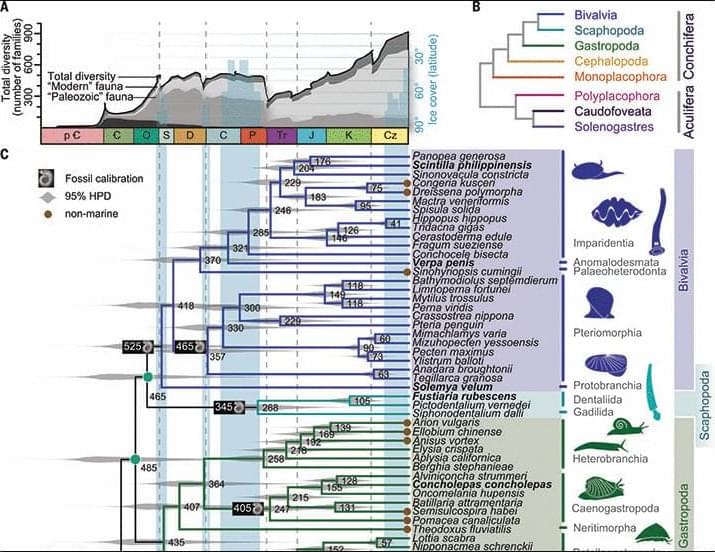

Extreme morphological disparity within Mollusca has long confounded efforts to reconstruct a stable backbone phylogeny for the phylum. Familiar molluscan groups—gastropods, bivalves, and cephalopods—each represent a diverse radiation with myriad morphological, ecological, and behavioral adaptations. The phylum further encompasses many more unfamiliar experiments in animal body-plan evolution. In this work, we reconstructed the phylogeny for living Mollusca on the basis of metazoan BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) genes extracted from 77 (13 new) genomes, including multiple members of all eight classes with two high-quality genome assemblies for monoplacophorans. Our analyses confirm a phylogeny proposed from morphology and show widespread genomic variation.