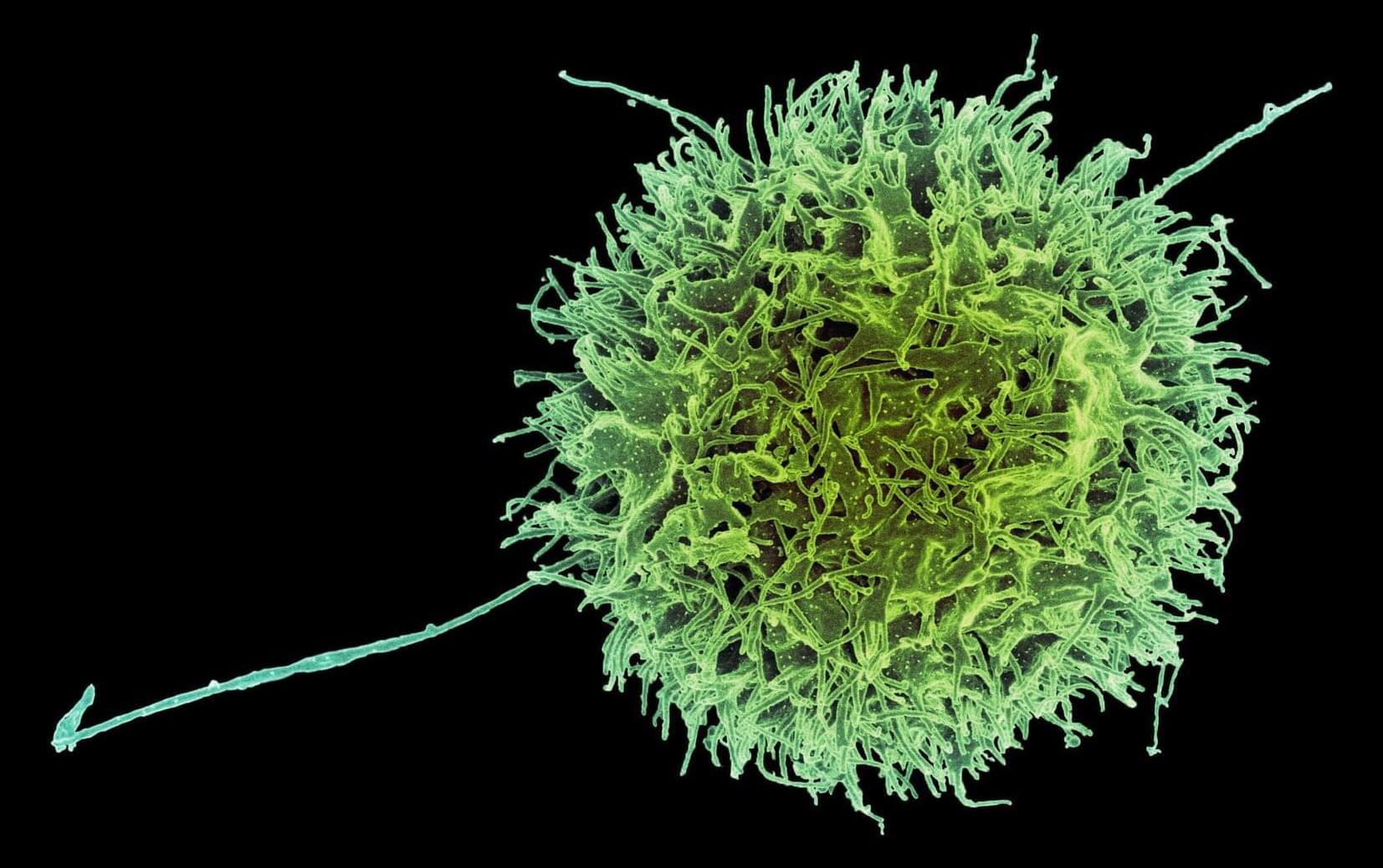

In nature, random fiber networks such as some of the tissues in the human body, are strong and tough with the ability to hold together but also stretch a lot before they fail. Studying this structural randomness—that nature seems to replicate so effortlessly—is extremely difficult in the lab and is even more difficult to accurately reproduce in engineering applications.

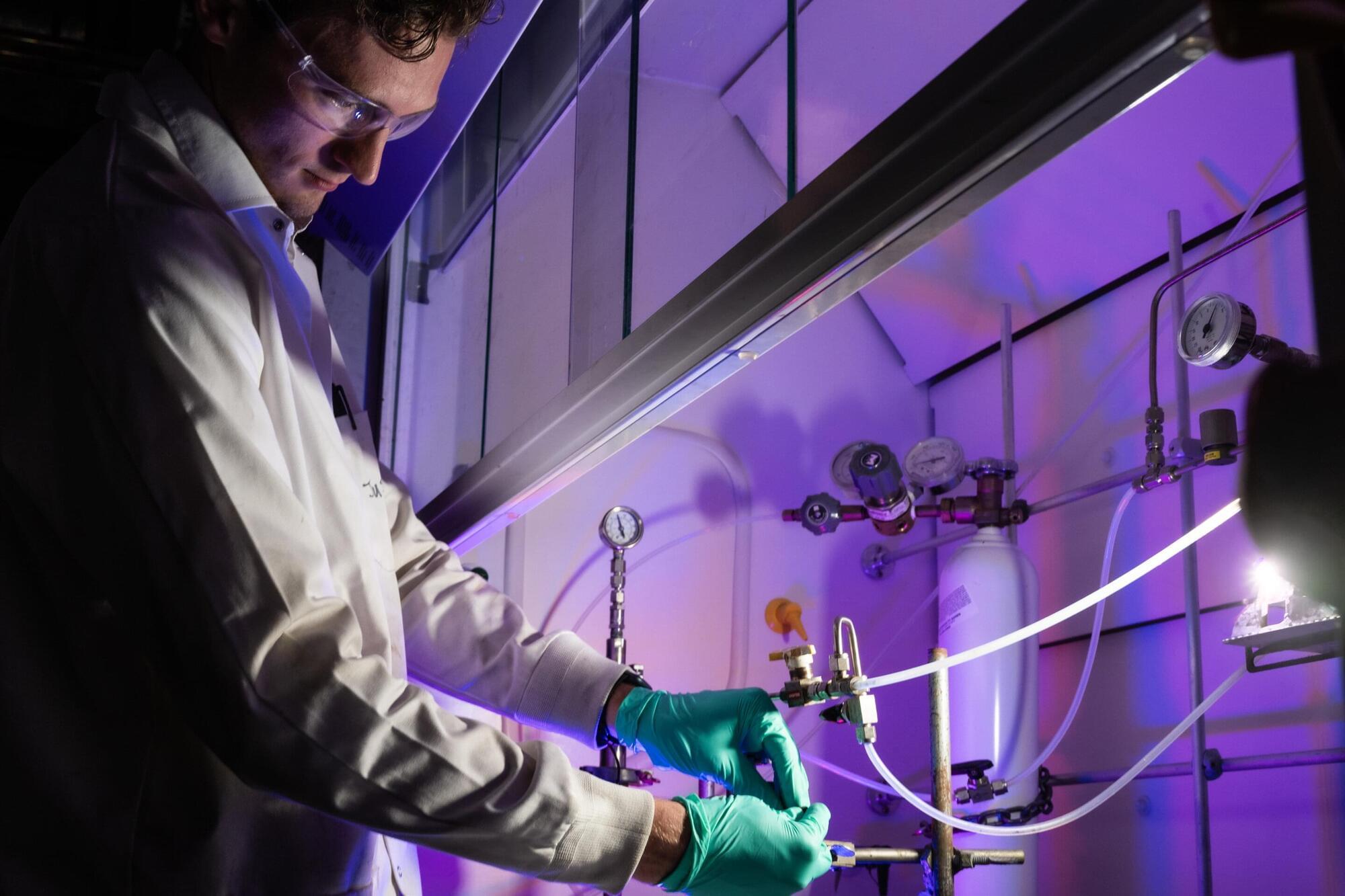

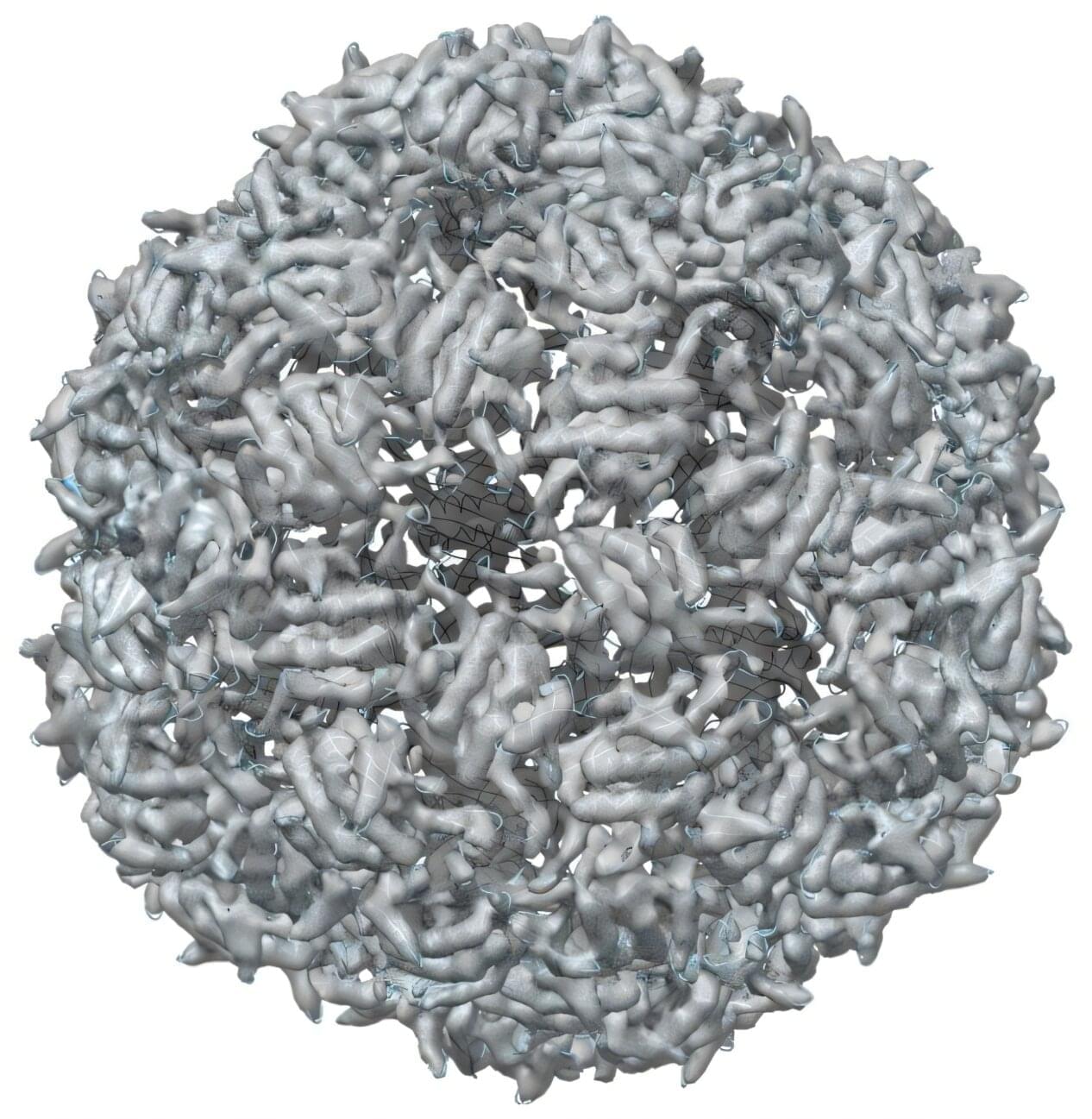

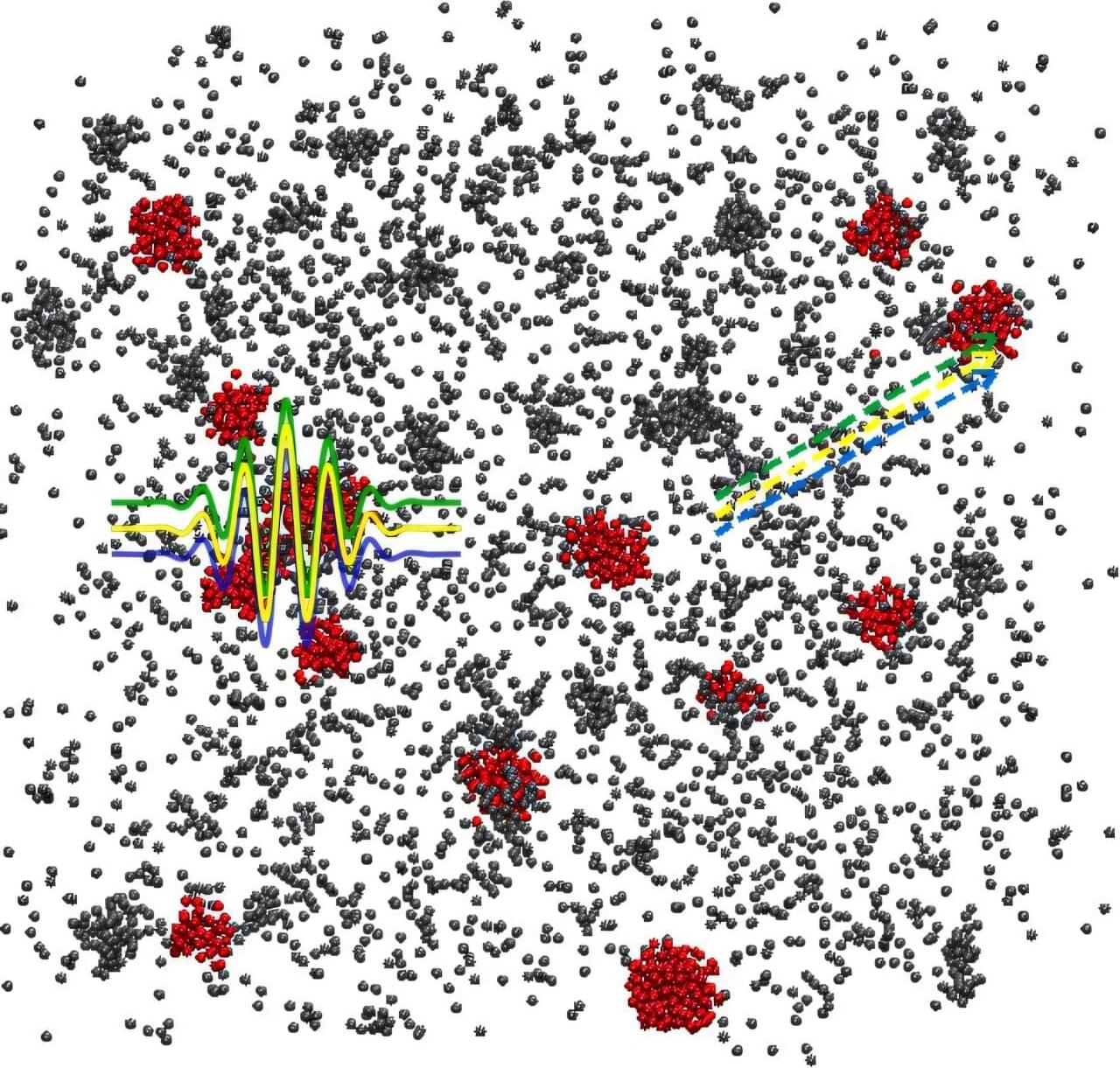

Recently, researchers at The Grainger College of Engineering, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute devised a method to repeatedly print random polymer nanofiber networks with desired characteristics and use computer simulations to tune the random network characteristics for improved strength and toughness.

“This is a big leap in understanding how nanofiber networks behave,” said Ioannis Chasiotis, a professor in the Department of Aerospace Engineering. “Now, for the first time, we can reproduce randomness with desirable underlying structural parameters in the lab, and with the companion computer model, we can optimize the network structure to find the network parameters, such as nanofiber density, that produce simultaneously higher network strength, stiffness and toughness.”