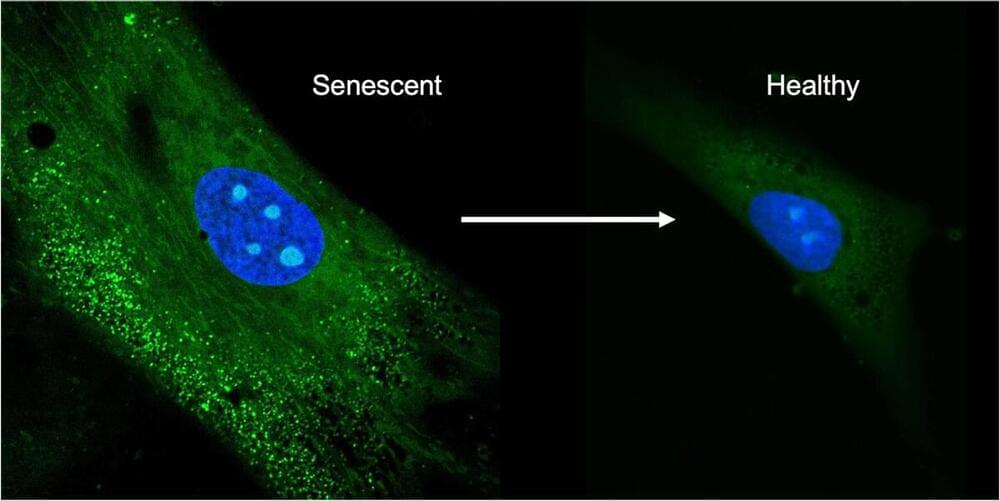

As we age, our bodies change and degenerate over time in a process called senescence. Stem cells, which have the unique ability to change into other cell types, also experience senescence, which presents an issue when trying to maintain cell cultures for therapeutic use. The biomolecules produced by these cell cultures are important for various medicines and treatments, but once the cells enter a senescent state they stop producing them, and worse, they instead produce biomolecules antagonistic to these therapeutics.

While there are methods to remove older cells in a culture, the capture rate is low. Instead of removing older cells, preventing the cells from entering senescence in the first place is a better strategy, according to Ryan Miller, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Hyunjoon Kong (M-CELS leader/EIRH/RBTE), a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

“We work with mesenchymal stem cells, that are derived from fat tissue, and produce biomolecules that are essential for therapeutics, so we want to keep the cell cultures healthy. In a clinical setting, the ideal way to prevent senescence would be to condition the environment that these stem cells are in, to control the oxidative state,” said Miller. “With antioxidants, you can pull them the cells out of this senescent state and make them behave like a healthy stem cell.”