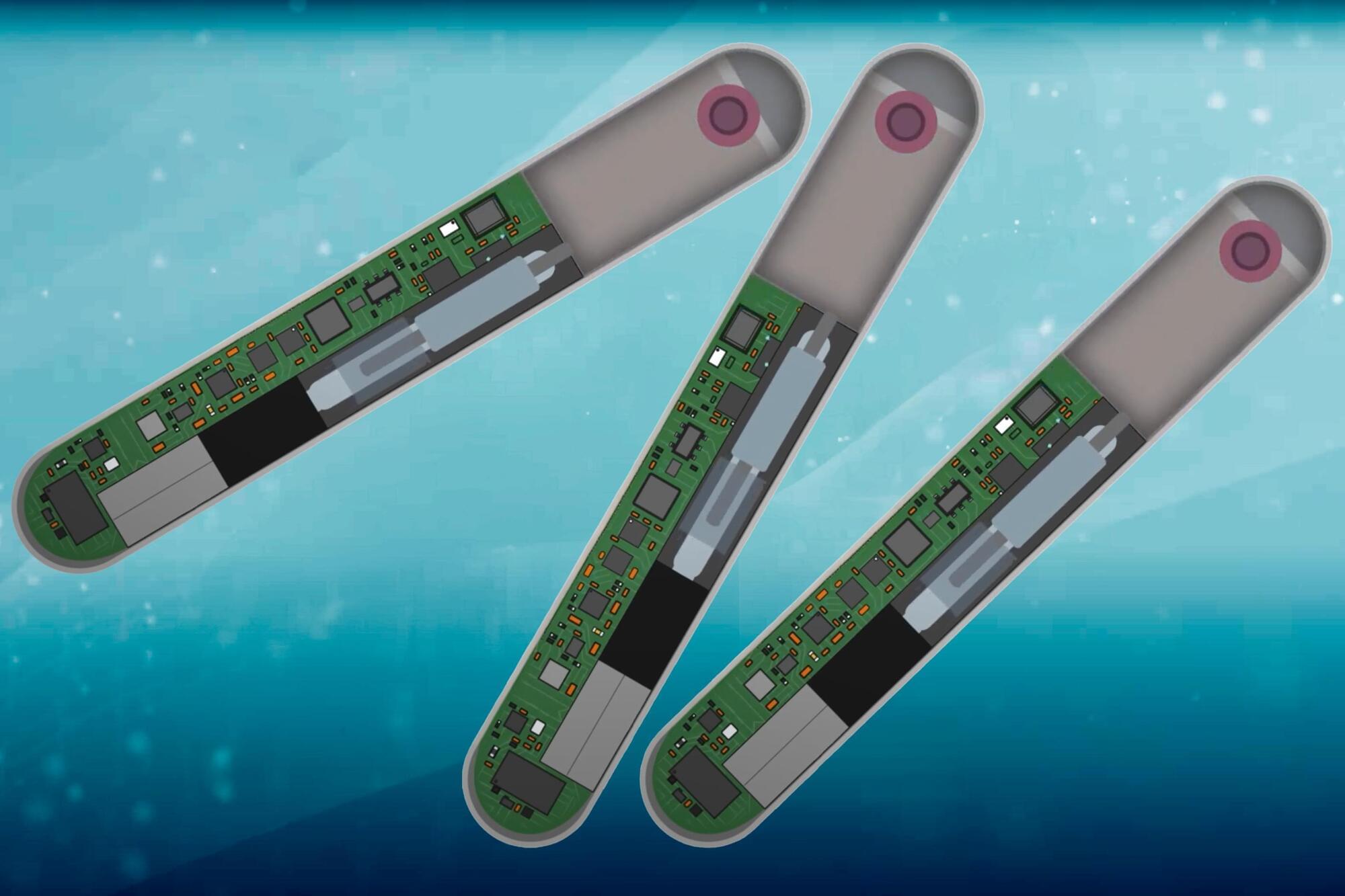

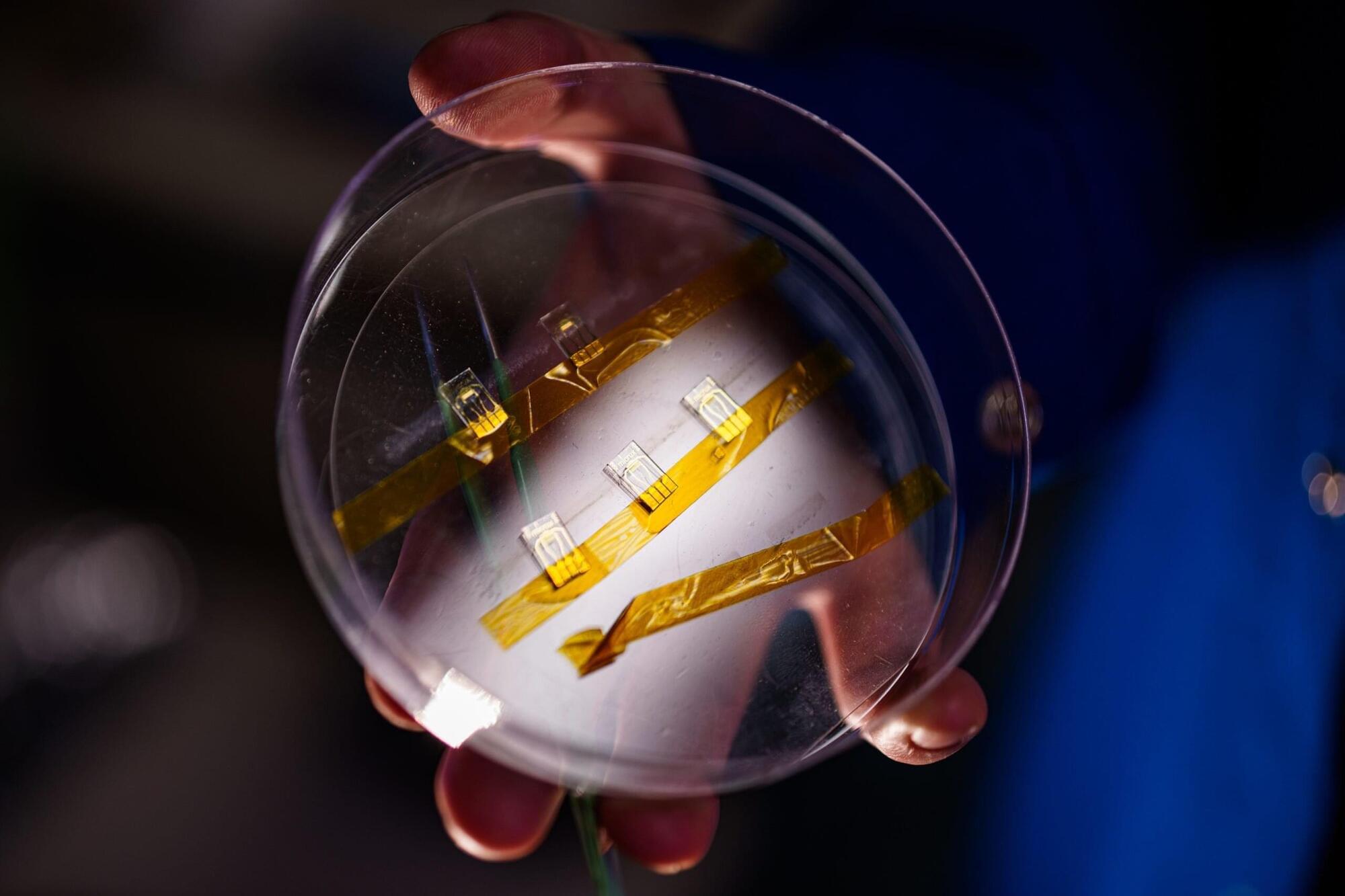

A new implantable sensor could reverse opioid overdoses. The device, developed at MIT and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, rapidly releases naloxone when an overdose is detected.

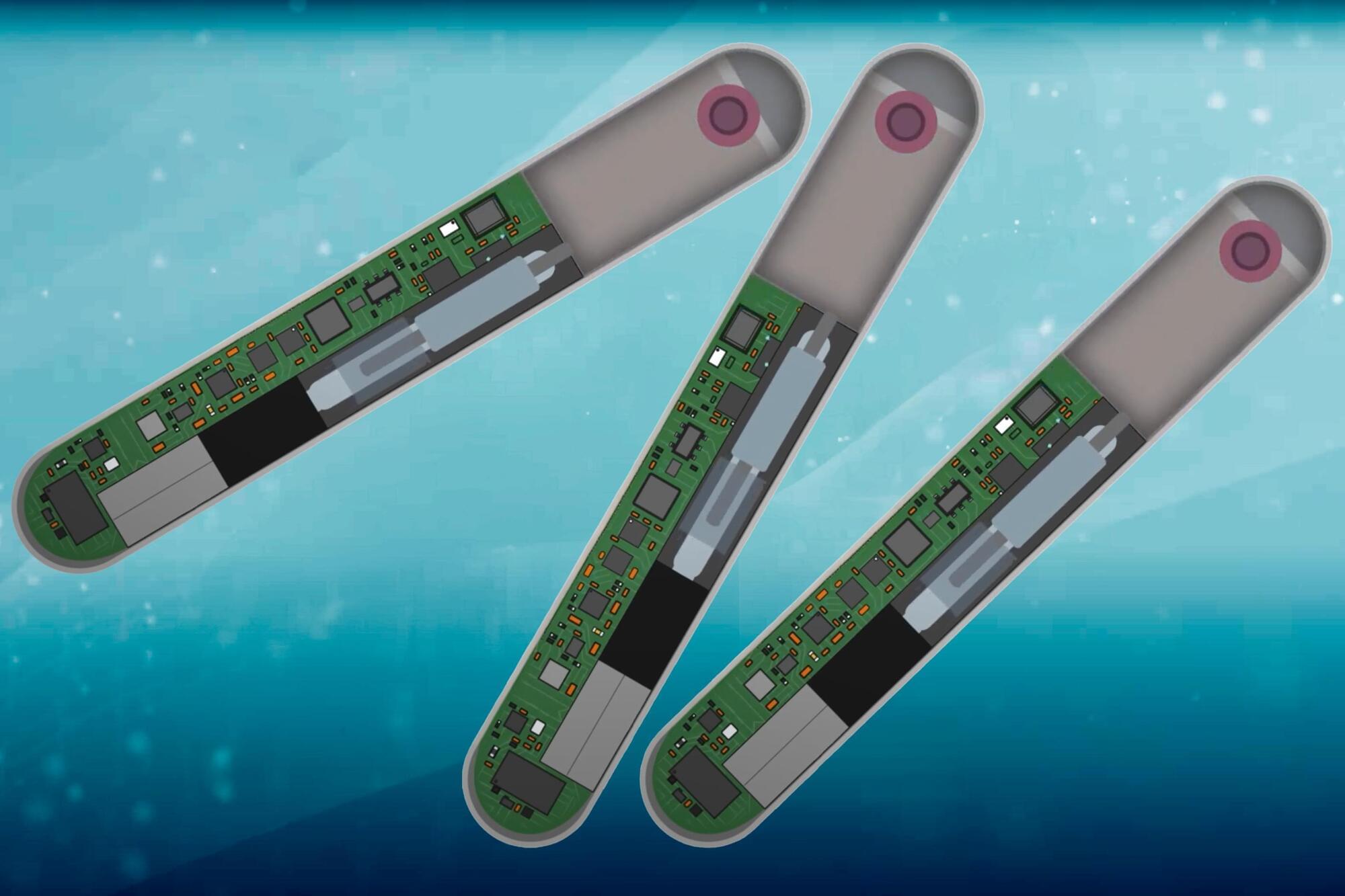

For the first time, a research team has successfully produced one of the most neutron-rich isotopes, hydrogen-6, in an electron scattering experiment.

The experiment at the spectrometer facility at the Mainz Microtron (MAMI) particle accelerator was a joint effort among the A1 Collaboration at the Institute of Nuclear Physics at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) and scientists from China and Japan. The team presents a new method for investigating light, neutron-rich nuclei and challenges our current understanding of multi-nucleon interactions.

“This measurement could only be carried out thanks to the unique combination of the excellent quality of the MAMI electron beam and the three high-resolution spectrometers of the A1 Collaboration,” emphasized Professor Josef Pochodzalla from the JGU Institute of Nuclear Physics. Researchers from Fudan University in Shanghai in China as well as from Tohoku University Sendai and the University of Tokyo in Japan were involved in the experiment.

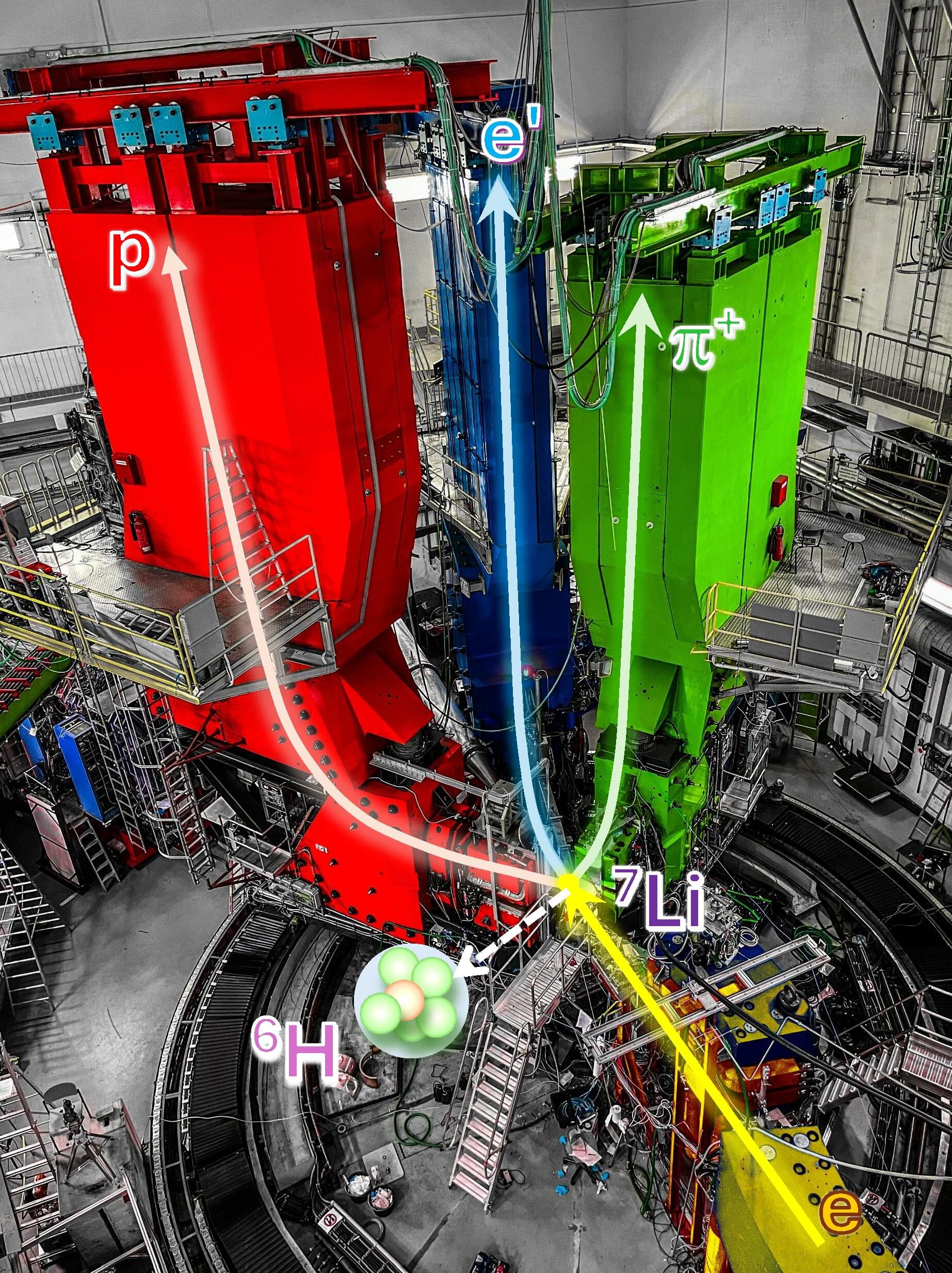

Lucid dreaming (LD) is a state of conscious awareness of the ongoing oneiric state, predominantly linked to REM sleep. Progress in understanding its neurobiological basis has been hindered by small sample sizes, diverse EEG setups, and artifacts like saccadic eye movements. To address these challenges in the characterization of the electrophysiological correlates of LD, we introduced an adaptive multi-stage preprocessing pipeline, applied to human data (male and female) pooled across laboratories, allowing us to explore sensor-and source-level markers of LD. We observed that, while sensor-level differences between LD and non-lucid REM sleep were minimal, mixed-frequency analysis revealed broad low-alpha to gamma power reductions during LD compared to wakefulness. Source-level analyses showed significant beta power (12−30 Hz) reductions in right central and parietal areas, including the temporo-parietal junction, during LD. Moreover, functional connectivity in the alpha band (8−12 Hz) increased during LD compared to non-lucid REM sleep. During initial LD eye signaling compared to baseline, source-level gamma1 power (30−36 Hz) increased in right temporo-occipital regions, including the right precuneus. Finally, functional connectivity analysis revealed increased inter-hemispheric and inter-regional gamma1 connectivity during LD, reflecting widespread network engagement. These results suggest that distinct source-level power and connectivity patterns characterize the dynamic neural processes underlying LD, including shifts in network communication and regional activation that may underlie the specific changes in perception, memory processing, self-awareness, and cognitive control. Taken together, these findings illuminate the electrophysiological correlates of LD, laying the groundwork for decoding the mechanisms of this intriguing state of consciousness.

Significance statement Lucid dreaming (LD) is a unique state of oneiric awareness, where individuals recognize they are dreaming while still in the dream. LD neural correlates remain elusive, as it is very rare and difficult to reproduce in the laboratory. Using an advanced preprocessing pipeline, we harmonized diverse EEG datasets to analyze the largest LD sample to date. We observed gamma power increases in the precuneus during initial eye lucidity signaling, beta power reductions in parietal areas, including the temporo-parietal junction, and enhanced alpha and gamma connectivity during LD over non-lucid REM sleep. These findings shed light on how the brain generates self-referential awareness and volitional action even during sleep.

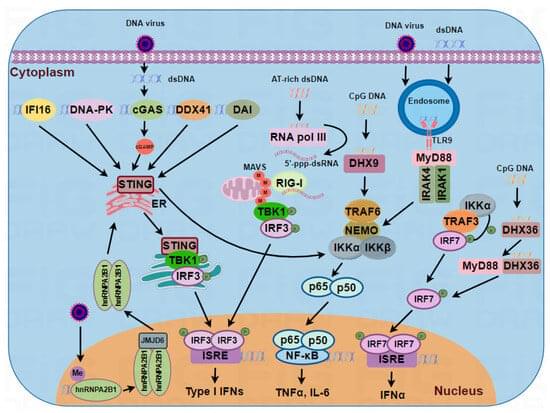

During viral infection, the innate immune system utilizes a variety of specific intracellular sensors to detect virus-derived nucleic acids and activate a series of cellular signaling cascades that produce type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is an oncogenic double-stranded DNA virus that has been associated with a variety of human malignancies, including Kaposi’s sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Infection with KSHV activates various DNA sensors, including cGAS, STING, IFI16, and DExD/H-box helicases. Activation of these DNA sensors induces the innate immune response to antagonize the virus. To counteract this, KSHV has developed countless strategies to evade or inhibit DNA sensing and facilitate its own infection. This review summarizes the major DNA-triggered sensing signaling pathways and details the current knowledge of DNA-sensing mechanisms involved in KSHV infection, as well as how KSHV evades antiviral signaling pathways to successfully establish latent infection and undergo lytic reactivation.

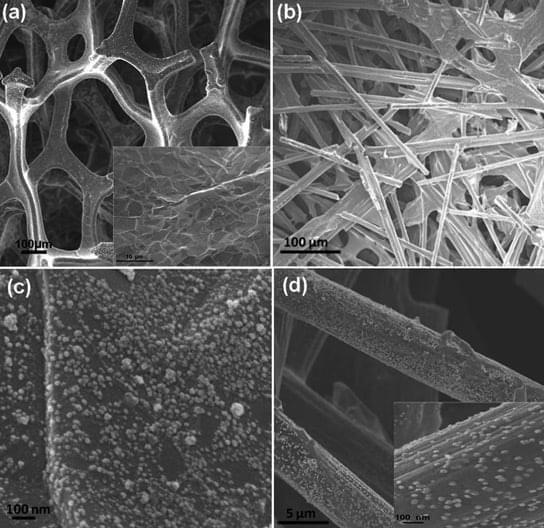

Graphene can support 50,000 times its own weight and can spring back into shape after being compressed by up to 80%. Graphene also has a much lower density than comparable metal-based materials. A new super-elastic, three-dimensional form of graphene can conduct electricity, and will probably pave t

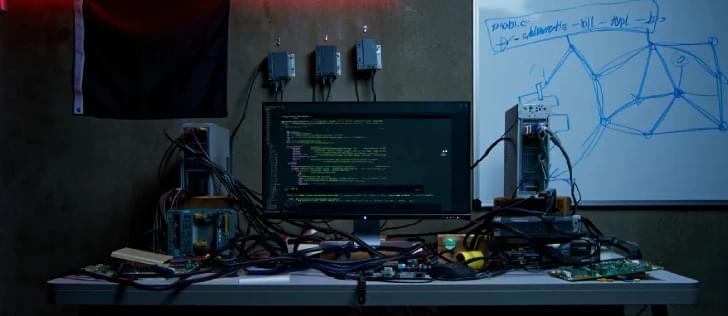

Cybersecurity researchers have flagged a new malicious campaign related to the North Korean state-sponsored threat actor known as Kimsuky that exploits a now-patched vulnerability impacting Microsoft Remote Desktop Services to gain initial access.

The activity has been named Larva-24005 by the AhnLab Security Intelligence Center (ASEC).

“In some systems, initial access was gained through exploiting the RDP vulnerability (BlueKeep, CVE-2019–0708),” the South Korean cybersecurity company said. “While an RDP vulnerability scanner was found in the compromised system, there is no evidence of its actual use.”

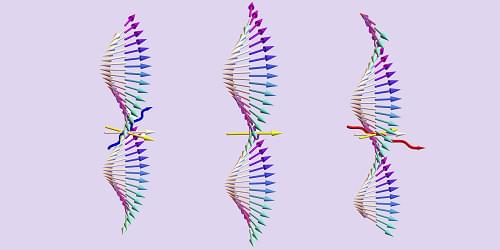

Scientists discovered a new Hall effect driven by spin currents in noncollinear antiferromagnets, offering a path to more efficient and resilient spintronic devices.

A research team led by Colorado State University graduate student Luke Wernert and Associate Professor Hua Chen has identified a previously unknown type of Hall effect that could lead to more energy-efficient electronic devices.

Their study, published in Physical Review Letters.

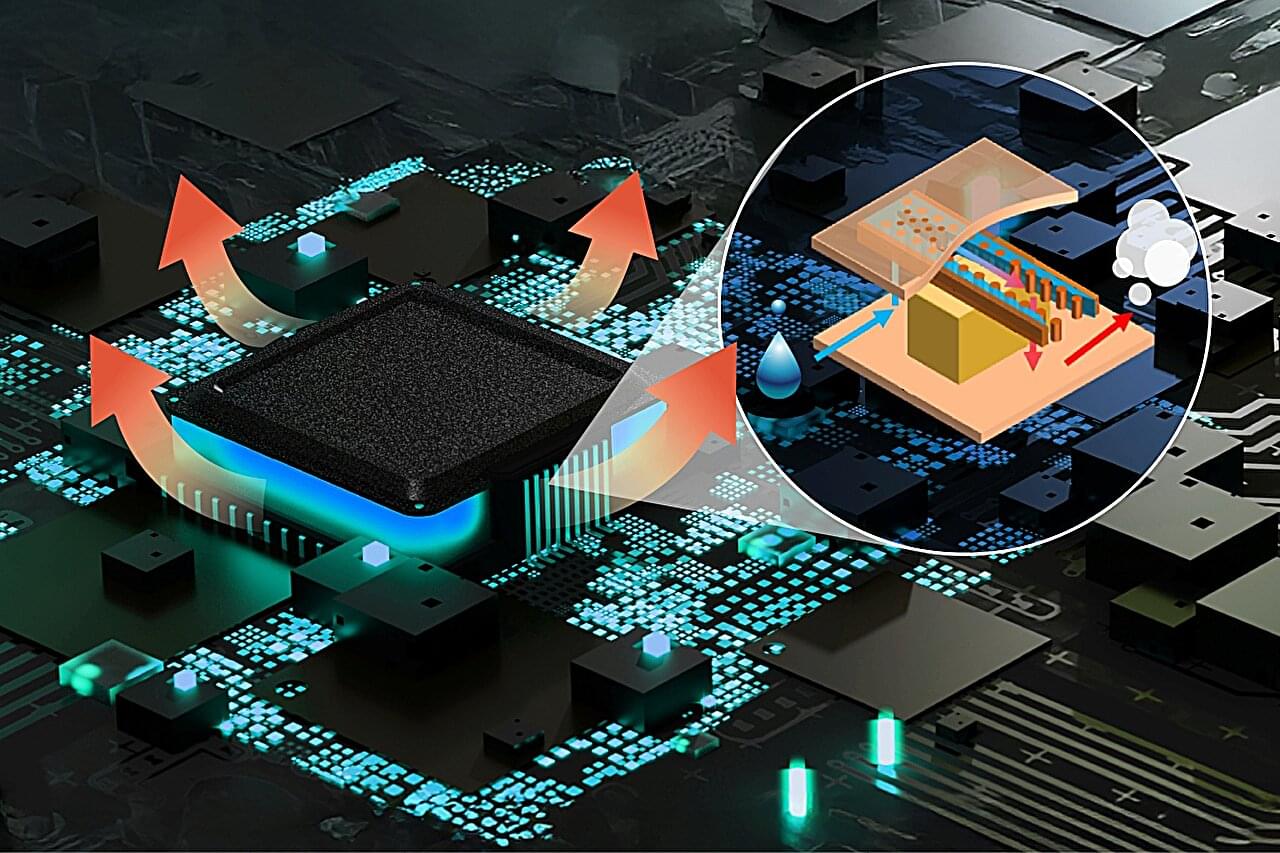

The exponential miniaturization of electronic chips over time, described by Moore’s law, has played a key role in our digital age. However, the operating power of small electronic devices is significantly limited by the lack of advanced cooling technologies available.

Aiming to tackle this problem, a study published in Cell Reports Physical Science, led by researchers from the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, describes a significant increase in performance for the cooling of electronic chips.

The most promising modern methods for chip cooling involve using microchannels embedded directly into the chip itself. These channels allow water to flow through, efficiently absorbing and transferring heat away from the source.