Quantum computers may be the next big thing in the tech world. Here are some ways to learn more about these devices.

France’s Sorbonne University plans to leave the Times Higher Education (THE) Rankings, adding its name to a growing number of universities rejecting lists that play one institution off against another. According to its president, most of these rankings are “black boxes” whose methods not only raise ethical questions but also fail to cover the breadth and diversity of university contributions.

“By deciding to stop sending our data to THE, we are leaving this specific ranking, but our criticism of major international university rankings is global,” Nathalie Drach-Temam, president of Sorbonne University, told Science|Business. “These rankings, built on selected quantitative indicators amalgamated into a single score, are not designed to evaluate research nor reflect the breadth and depth of the missions of research and higher education institutions.”

From the UK-based Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) ranking to the US News and World Report (USWR), university rankings set out to measure how well a higher education institution performs and how its performance and quality compare to its peers. Prospective students turn to them for guidance, and governments and investors base their research funding decisions on them.

Brian Cory Dobbs’s documentary promotes the baseless idea that Mars was once inhabited by an advanced civilisation. But there’s some value in how it inadvertently documents a generation of otherwise-sensible scientists, says Simon Ings

By Simon Ings

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is approximately two times higher in African Americans (AA) compared to white/European-ancestry (EA) individuals living in the U.S. Some of this is due to social determinants of health such as disparities in health care access and quality of education, biases in testing and higher rates of AD risk factors such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes in those who identify as African American.

Although many studies have examined differences in gene expression (a measure of the amount of protein encoded by a gene) in brain tissue from AD cases and controls in EA or mixed ancestry cohorts, the number of AA individuals in these studies was unspecified or too small to identify significant findings within this group alone.

In the largest AD study conducted in brain tissue from AA donors, researchers from Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine have identified many genes, a large portion of which had not previously been implicated in AD by other genetic studies, to be significantly more or less active in tissue from AD cases compared to controls. The most notable finding was a 1.5 fold higher level of expression of the ADAMTS2 gene in brain tissue from those with autopsy-confirmed AD.

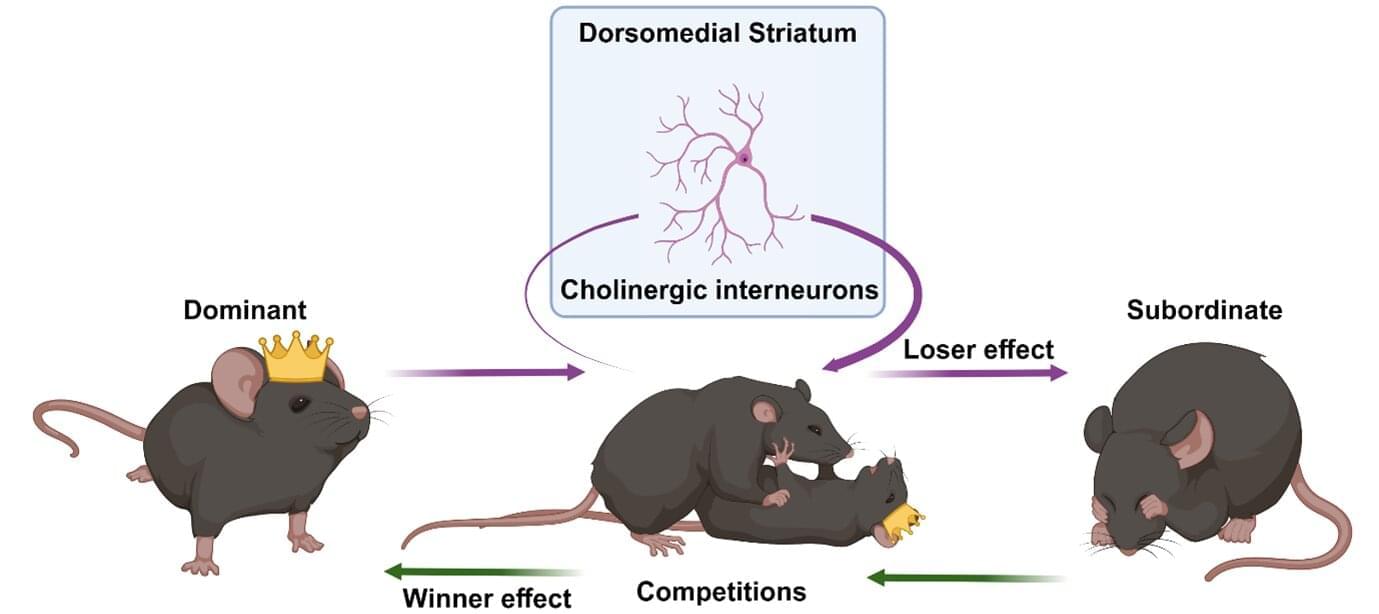

Social hierarchies are everywhere—think of high school dramas, where the athletes are portrayed as the most popular, or large companies, where the CEO makes the important decisions. Such hierarchies aren’t just limited to humans, but span the animal kingdom, with dominant individuals getting faster food access, higher mating priority, and bigger or better territories. While it’s long been thought that winning or losing can influence the position of an individual within a social hierarchy, the brain mechanisms behind these social dynamics have remained a mystery.

In iScience, researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) investigate the neurological basis of social hierarchy in male mice, pinpointing the neurons they believe crucial in determining these social hierarchy dynamics.

“You may think that being dominant in the animal kingdom is all about physical attributes, like size. But interestingly, we’ve found that it seems to be a choice, based on previous experience,” said Professor Jeffery Wickens, head of the Neurobiology Research Unit at OIST and co-author on this study. “The brain circuitry involved in these decisions is well conserved between mice and humans, so there are likely useful parallels to be drawn.”

Researchers at UCL Institute of Education, King’s College London, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and UCLA report that perceived social threats in early adolescence are associated with altered connectivity in default mode, dorsal attention, frontoparietal, and cingulo-opercular networks and with higher mental health symptom scores months later.

Adolescence is a difficult age, a time of rapid neurobiological and psychological change amidst shifting social standing. In 2021, CDC reported that 40% of U.S. high school students struggled with persistent sadness or hopelessness, and more than one in six had made a suicide plan.

Perceived threats in a child’s social environment, within the family, at school, and in the neighborhood, are known risk factors for adolescent psychopathology.

Scientists have found a nanoparticle-inspired solution to the age-old strength issue of polymer glasses. Seasoning the polymer glass recipe with single-chain nanoparticles, which are tiny, folded-up polymer strands, can make the glass stronger, tougher, and easier to process by acting as reinforcements.

In a study published in Physical Review Letters, researchers from China overcame these issues by using nanoparticles made from balled-up single-chain polymers (SCNPs). According to the researchers, their approach opens a new pathway for creating advanced polymer glasses that combine strength, toughness, and processability in ways previously thought to be incompatible.

Polymer glass, also known as plexiglass, is widely used for making eyeglasses and enclosures for aquariums and museums. For decades, researchers have been seeking ways to enhance the mechanical properties of plexiglass, with a primary focus on improving its strength and toughness.

This is one of the Royal Institute of Philosophy’s 15-minute Philosophy Briefings, a series in which eminent philosophers provide their own view of a key philosophical topic, in straightforward and accessible language.

Each one is designed to be a resource for anyone who wants to know more about these questions, whether you are covering them at A-level, teaching them at A-level, studying Philosophy at university, or are simply curious to know more.

David Chalmers, Professor of Philosophy and Neural Science at New York University and co-director of NYU’s Center for Mind, Brain, and Consciousness, looks at whether there exist philosophical zombies.

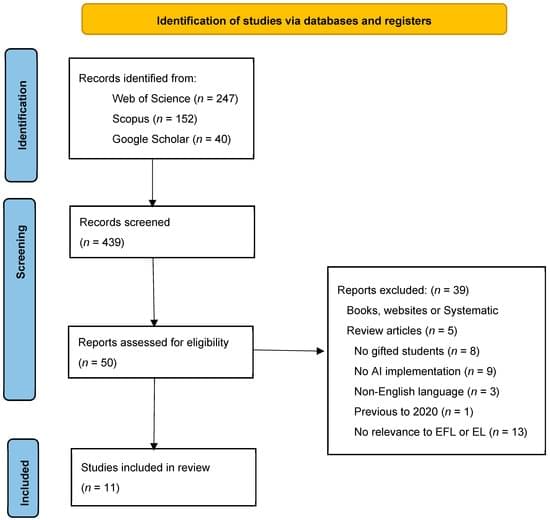

There is a growing body of literature that focuses on the applicability of artificial intelligence (AI) in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and English Language (EL) classrooms; however, educational application of AI in the EFL and EL classroom for gifted students presents a new paradigm. This paper explores the existing research to highlight current practices and future possibilities of AI for teaching EFL and EL to address gifted students’ special needs. In general, the uses of AI are being established for class instruction and intervention; nevertheless, there is still uncertainty about practitioner use of AI with gifted students in EFL and EL classrooms. This review identifies 42 examples of GenAI Models that can be used in gifted EFL and EL classrooms.