Category: cryonics – Page 16

NBC & Phil Noyce Plan Cryonics Drama

NBC is developing an untitled cryonics-themed project which hails from writer and executive producer David Slack and filmmaker Phillip Noyce who will direct the pilot and executive produce.

Sony Television produces the series which follows an enigmatic billionaire who has gathered more than 250 people who attempt to cheat death by undergoing cryogenic suspension in hopes that a future breakthrough would someday allow them to be brought back to life.

However, as these people from different moments in time wake up, they soon realise you can’t cheat death without paying a price. Josh Berman and Chris King will also serve as executive producer. Noyce also helmed the pilots of and executive produced ABC’s “Revenge” and FOX’s “The Resident”.

Artifical-Death (maintaining a signal from the living person using MVT aware circuits) is possible using current technology

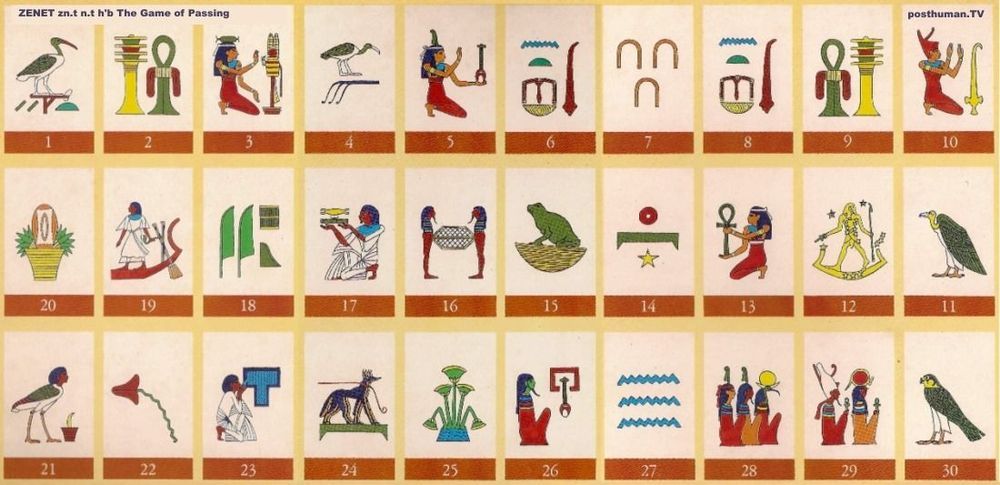

There are good technical reasons why prototypes use the ancient game of Zenet as the interface. Although I do not rule out alternative approaches using the underlying designs and principles, there are unique reasons to choose Zenet — the only method recorded in ancient Egypt whereby the dead and living could communicate. Notwithstanding my background in neural net and hybrid AI in game software development, especially active divination systems; Zenet is the most elegant solution to bridge the worlds (between living and dead) since the rules and objectives vary slightly between the two, and smooth transition between these perspectives can occur in real-time. An objection to Cryogenics is the dead take energy and resources from the living. By making the Zenet boxes solar powered this will not impact on resources of the living, and also will provide a more authentic experience of sun rise and solar changes, important in solar theology of Ra and in Zenet. The game concerns movement of the solar b(ark). On a pragmatic note — the range of awareness can extend just to events and moves in the Zenet game. Even this task is far from trivial using silicon technology, and I don’t envisage anything like “full resurrection” or retention of current memories and so on as feasible for some time.

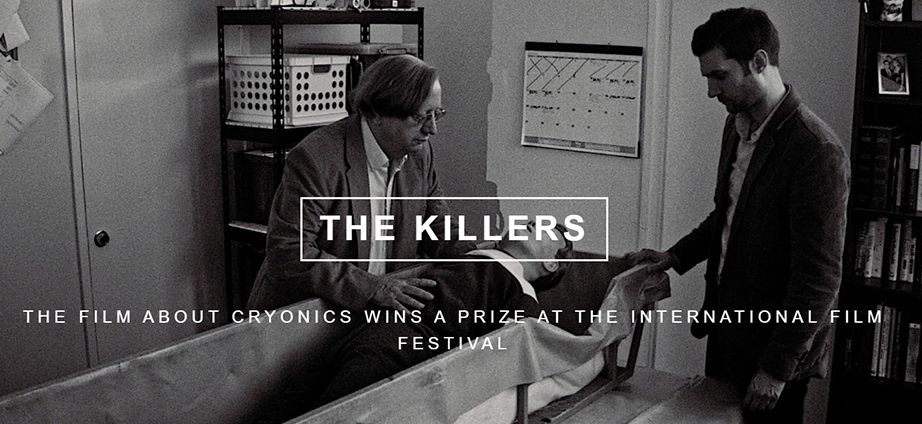

The film about cryonics wins a prize at the international film festival

The Killers, the short film about cryonics shot by Russian director Vlad Kozlov, who works in the USA, won a Best Director prize at the 37th Flickers: Rhode Island International Film Festival (RIIFF).

RIIFF is one of the most important international film festivals supporting independent filmmakers. The festival has been held annually since 1982 during the second week of August and lasts six days. Its main goal is to discover new talents of independent cinema. More than 5,426 independent films selected from more than 68,000 received applications were presented to the public during the time of existence of the festival. In 2019, 321 films from 51 countries were presented at the festival, which was held from August 6 to August 11 in Rhode Island, USA.

Cryonics as the central element of the plot was shown in a film of this level for the first time. The main roles in the film are played by world-famous actors such as Sherilyn Fenn (Twin Peaks) and Franco Nero (Django). The role of Max, the main character, was played by a young and promising American actor Jeff DuJardin, who had previously worked with Vlad Kozlov on the set of Silent Life, the film about the star of silent film Rudolf Valentino. The producers of the film are Vlad Kozlov, Natalia Dar, Yury Ponomarev, Dmitry Pristankov and David Roberson.