Carl knox / ozgrav, ARC centre of excellence for gravitational wave discovery, swinburne university of technology.

The specific event they observed and analyzed is so rare that it has only been seen three other times throughout history.

Carl knox / ozgrav, ARC centre of excellence for gravitational wave discovery, swinburne university of technology.

The specific event they observed and analyzed is so rare that it has only been seen three other times throughout history.

NASA’s Discover supercomputer simulated the extreme conditions of the distant cosmos.

A team of scientists from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center used the U.S. space agency’s Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS) Discover supercomputer to run 100 simulations of jets emerging from supermassive black holes.

The scientists set out to better understand these jets — massive beams of energetic particles shooting out into the cosmos — as they play a crucial role in the evolution of the universe.

This could help us probe into the lesser-known field of quantum gravity.

A collaborative team of researchers in the U.S. created a holographic wormhole and sent a message through it. This is the first known report of a quantum simulation of a holographic wormhole on a quantum processor.

However, the two theories are fundamentally incompatible and the holographic principle is a guide that can help us combine the two.

Metamorworks/iStock.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity helps us to understand the physical world such as astronomical objects with high energies or matter densities. Quantum mechanics on the other hand, describes matter at atomic and subatomic scales.

An older universe existed before the Big Bang, and proof for its existence can still be found in black holes, according to a Nobel Prize-winning physicist. Sir Roger Penrose made the assertion after receiving the award for advances in Einstein’s general theory of relativity and proof of black hole existence. Sir Roger contends that inexplicable regions of electromagnetic radiation in the sky, known as ‘Hawking Points,’ represent vestiges of an earlier universe.

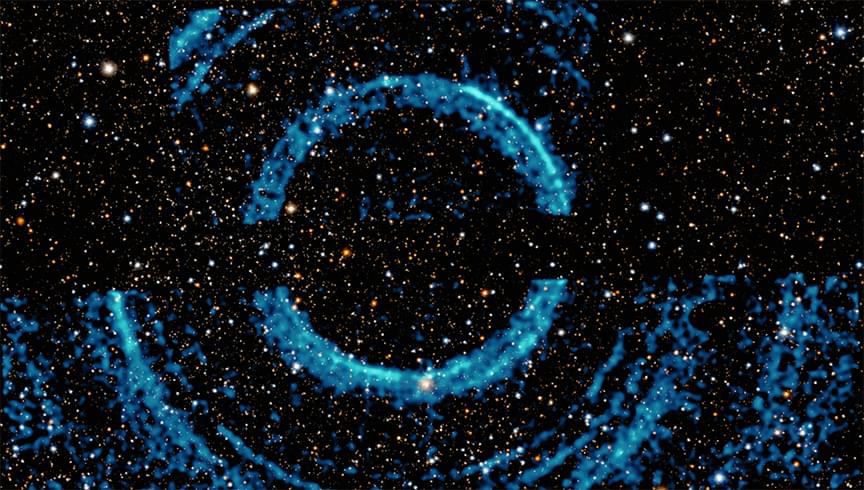

Scientists have made it possible to listen to the light echoes of a black hole by turning astronomical data into souns.

An international team of researchers are suggesting that our understanding of the origins of our universe may need some updates.

As detailed in a new paper published this week in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, they say the universe may have begun with a “Big Bounce” rather than a Big Bang.

In other words, the cosmos may have been born following of the end of a previous cosmological phase — a bounce — and not the result of space-time inflating exponentially into existence.

As well as admiring beautiful pictures of space, you can also listen to those pictures via sonifications. These take images and translate them into eerie sounds to illustrate the wonderful and strange phenomena of our universe. NASA’s latest sonification illustrates the rings of X-rays that have been observed echoing around a black hole in the V404 Cygni system.

The sonification was made using data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, both of which look in the X-ray wavelength. The data from the optical wavelength come from the Pan-STARRS telescope in Hawaii. Taken together, you can see how the X-ray bursts propagate outward from a central point which is the black hole. The black hole itself remains invisible, as it absorbs all light.

However, even though black holes are themselves invisible, the material around them can glow brightly. As material like dust and gas is attracted to the black hole due to gravity, it joins into a swirling disk around the black hole called an accretion disk. This material rubs together and creates heat due to friction, and can become so hot that it glows.