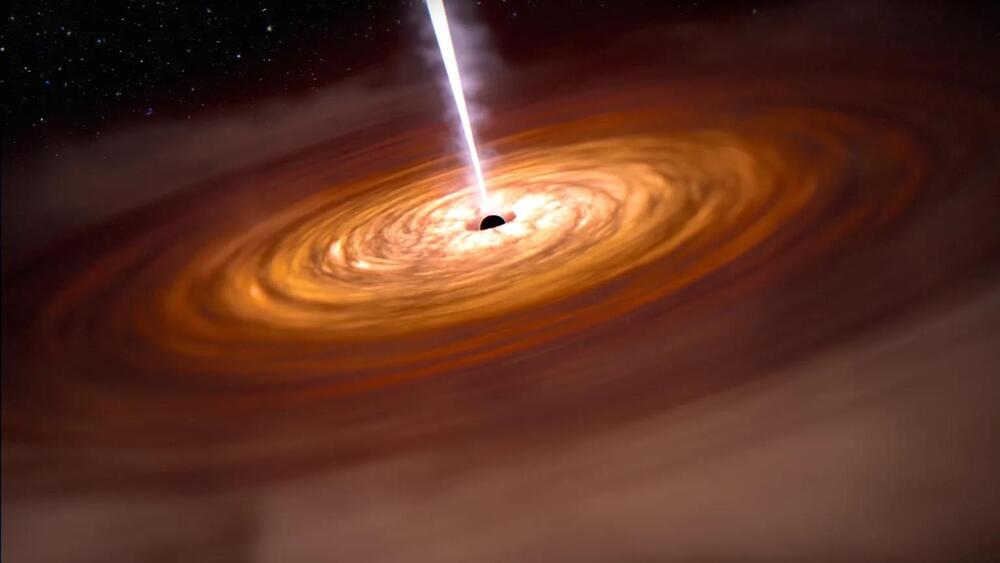

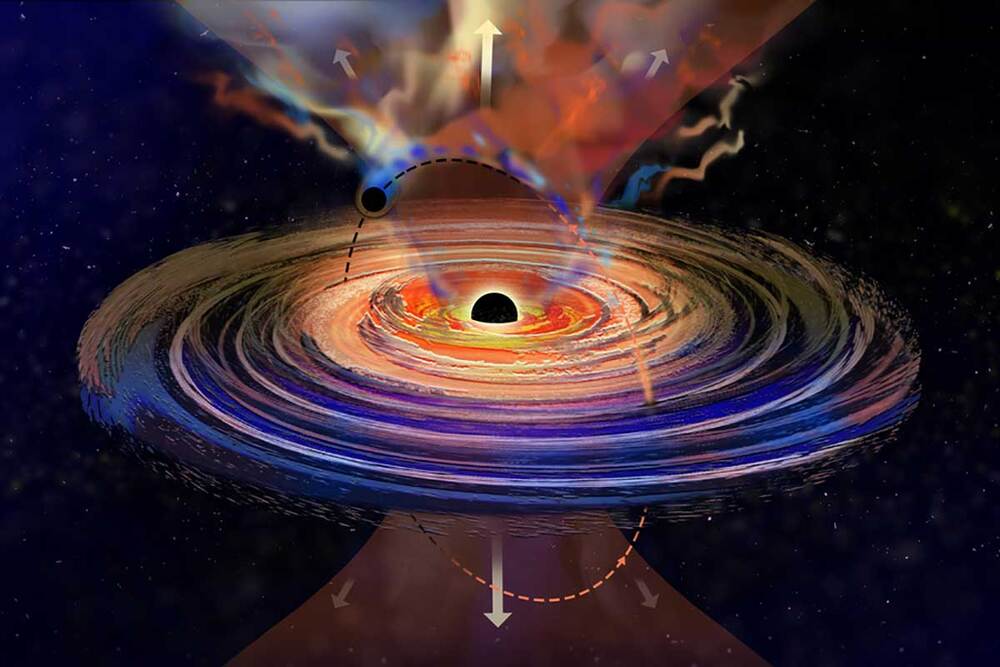

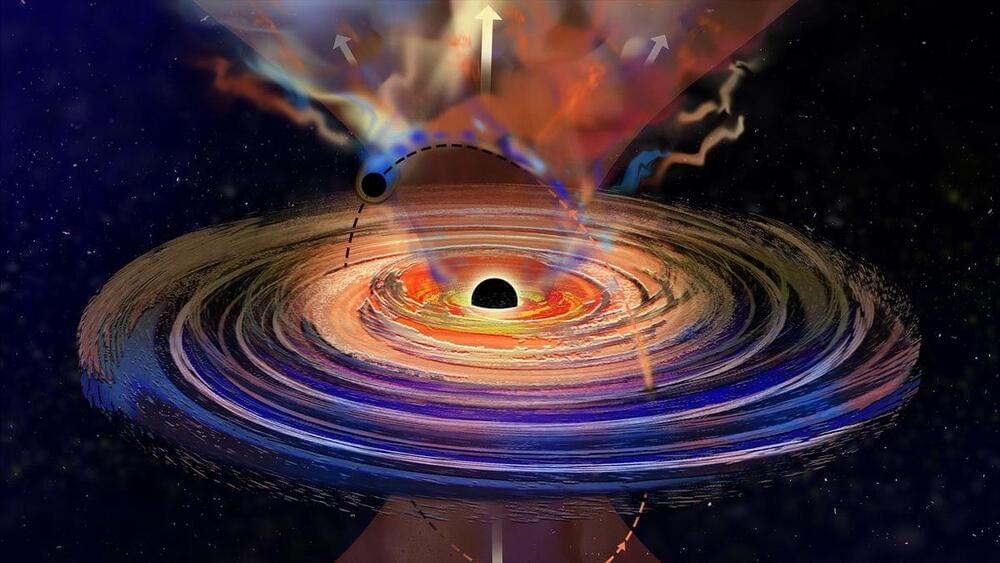

Ever wonder where all the active supermassive black holes are in the universe? Now, with the largest quasar catalog yet, you can see the locations of 1.3 million quasars in 3D.

The catalog, Quaia, can be accessed here.

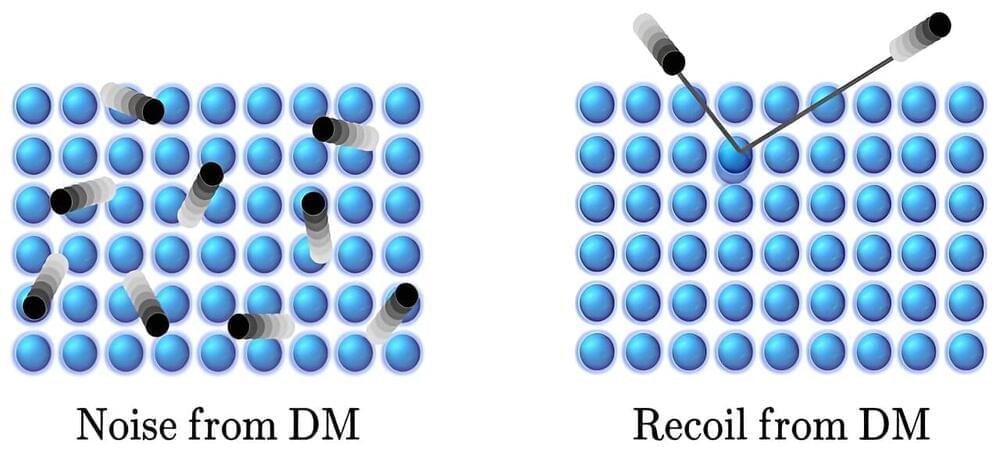

“This quasar catalog is a great example of how productive astronomical projects are,” says David Hogg, study co-author and computational astrophysicist at the Flatiron Institute, in a press release. “Gaia was designed to measure stars in our galaxy, but it also found millions of quasars at the same time, which give us a map of the entire universe.” By mapping and seeing where quasars are across the universe, astrophysicists can learn more about how the universe evolved, insights into how supermassive black holes grow, and even how dark matter clumps together around galaxies. Researchers published the study this week in The Astrophysical Journal.