Gauging whether or not we dwell inside someone else’s computer may come down to advanced AI research—or measurements at the frontiers of cosmology.

Category: cosmology – Page 156

How are extreme “blue supergiant” stars born? Astronomers may finally know

The team of scientists set about investigating this by analyzing 59 early B-type blue supergiants located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way, and creating novel stellar simulations.

“We simulated the mergers of evolved giant stars with their smaller stellar companions over a wide range of parameters, taking into account the interaction and mixing of the two stars during the merger,” study leader and IAC researcher Athira Menon said in a statement. “The newly born stars live as blue supergiants throughout the second-longest phase of a star’s life, when it burns helium in its core.”

The team’s findings suggest that blue supergiants slip into an evolutionary gap in conventional stellar physics — a phase of stellar evolution where astronomers would not expect to see stars. The question is, Can this explain the remarkable properties of blue supergiant stars? It seems the answer is yes.

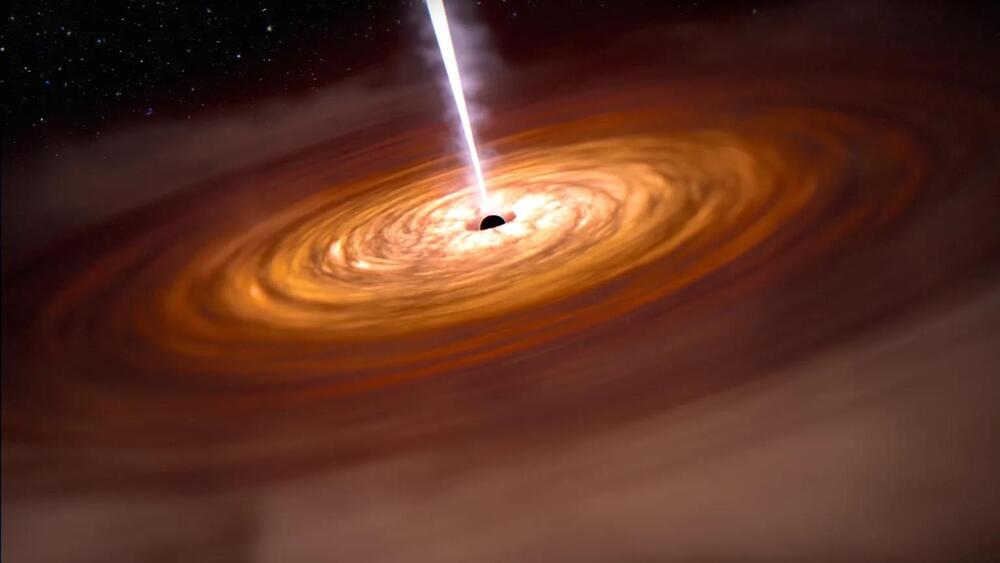

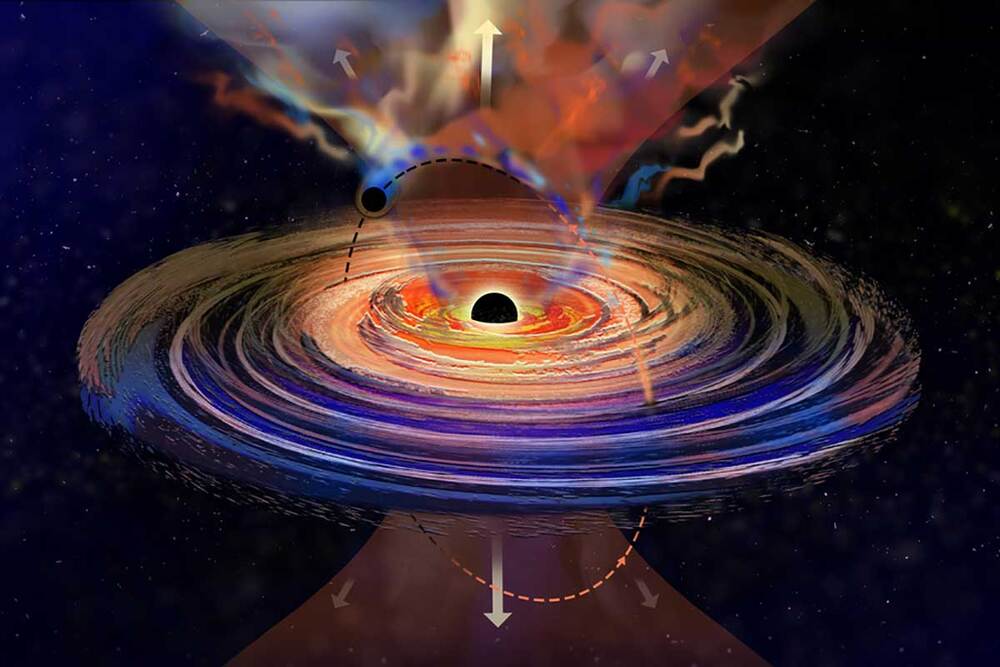

Was Our Universe Created Inside the Quantum Chaos of a Black Hole from Another Universe?

Black holes are renowned and frightening phenomena—areas characterized by infinite gravitational force, rendering escape impossible. The process of forming a black hole is relatively uncomplicated: it involves compressing a sufficient amount of mass below a specific size threshold. Once this threshold is surpassed, gravity prevails over all other forces, resulting in the creation of a black hole.

The critical threshold varies depending on the quantity of mass being condensed. For an average human, this threshold is comparable to the size of an atomic nucleus. Conversely, for the Earth, compressing its entirety into the volume of a chickpea would generate a black hole of comparable size. Similarly, for a typical star with several times the mass of the Sun, the resulting black hole would span a few miles—a dimension akin to an average city.

Interestingly, amalgamating all the matter in the universe in an attempt to create the largest possible black hole would yield a black hole roughly the size of the universe itself.

Astronomers map 1.3 million supermassive black holes

Ever wonder where all the active supermassive black holes are in the universe? Now, with the largest quasar catalog yet, you can see the locations of 1.3 million quasars in 3D.

The catalog, Quaia, can be accessed here.

“This quasar catalog is a great example of how productive astronomical projects are,” says David Hogg, study co-author and computational astrophysicist at the Flatiron Institute, in a press release. “Gaia was designed to measure stars in our galaxy, but it also found millions of quasars at the same time, which give us a map of the entire universe.” By mapping and seeing where quasars are across the universe, astrophysicists can learn more about how the universe evolved, insights into how supermassive black holes grow, and even how dark matter clumps together around galaxies. Researchers published the study this week in The Astrophysical Journal.

Is The Universe 26.7 Billion Years Old? Brian Cox on The Big Bang

#jwst Subscribe to Science Time: https://www.youtube.com/sciencetime24Div…

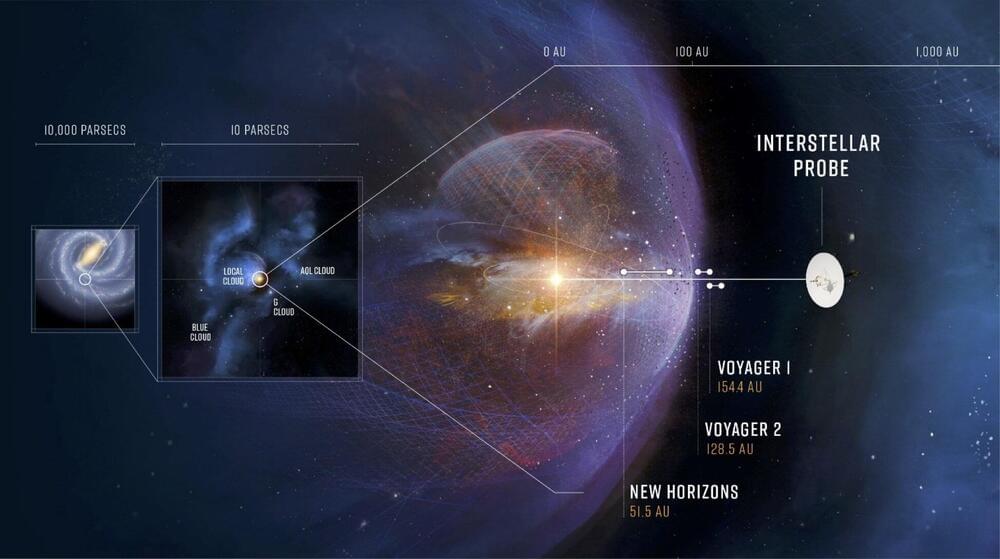

Mapping the best route for a spacecraft traveling beyond the sun’s sphere of influence

The heliosphere—made of solar wind, solar transients, and the interplanetary magnetic field—acts as our solar system’s personal shield, protecting the planets from galactic cosmic rays. These extremely energetic particles accelerated outwards from events like supernovas and would cause a huge amount of damage if the heliosphere did not mostly absorb them.

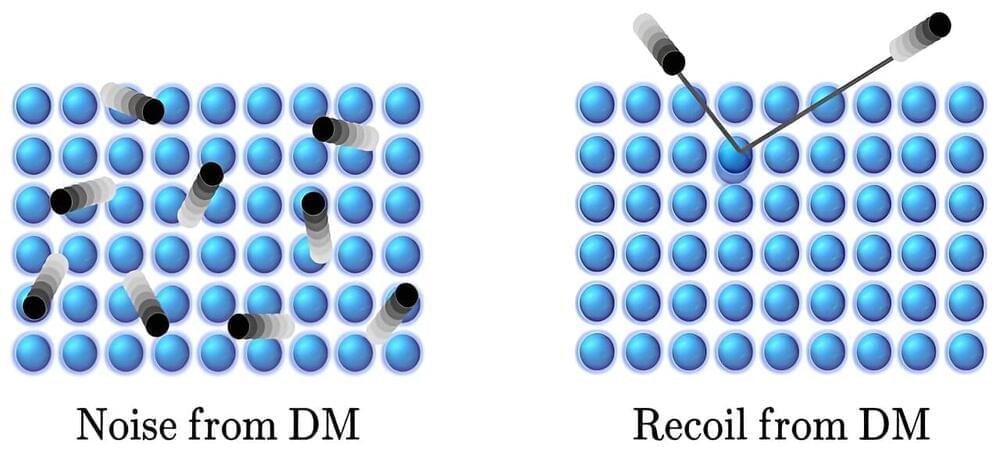

Physicists propose new way to search for dark matter: Small-scale solution could be key to solving large-scale mystery

Ever since its discovery, dark matter has remained invisible to scientists despite the launch of multiple ultra-sensitive particle detector experiments around the world over several decades.

Now, physicists at the Department of Energy’s (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory are proposing a new way to look for dark matter using quantum devices, which might be naturally tuned to detect what researchers call thermalized dark matter.

Most dark matter experiments hunt for galactic dark matter, which rockets into Earth directly from space, but another kind might have been hanging around Earth for years, said SLAC physicist Rebecca Leane, who was an author of the new study.

Kugelblitz Black Holes

Learn more about the game and see it in action at https://upperstory.com/turingtumble/?utm_source=YouTube&utm_medium=XXXXUse the coupon code ISAACARTHUR for…