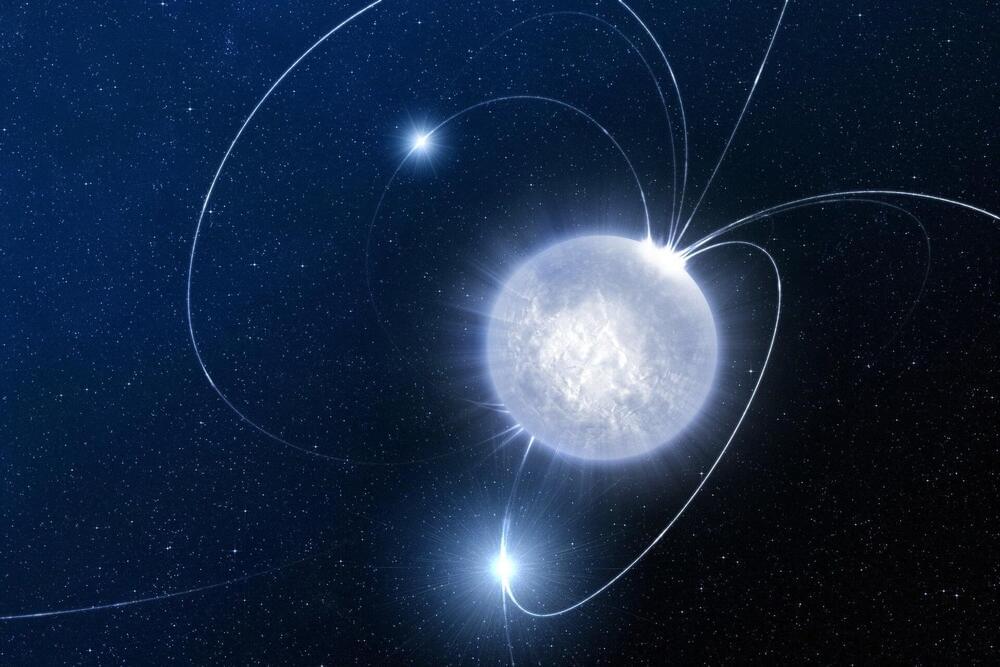

Scientists may be one step closer to unlocking one of the great mysteries of the universe after calculating that neutron stars might hold a key to helping us understand elusive dark matter.

If you were to throw a message in a bottle into a black hole, all of the information in it, down to the quantum level, would become completely scrambled. Because in black holes this scrambling happens as quickly and thoroughly as quantum mechanics allows. They are generally considered nature’s ultimate information scramblers.

Stephen Hawking and Jacob Bekenstein calculated the entropy of a black hole in the 1970s, but it took physicists until now to figure out the quantum effects that make the formula work.

By Leah Crane

But when it comes to the origin of the Universe, we don’t know what forces are at play. We actually can’t know, since to know such force (or better, such fields and their interactions) would necessitate knowledge of the initial state of the Universe. And how could we possibly glean information from such a state in some uncontroversial way? In more prosaic terms, it would mean that we could know what the Universe was like as it came into existence. This would require a god’s eye view of the initial state of the Universe, a kind of objective separation between us and the proto-Universe that is about to become the Universe we live in. It would mean we had a complete knowledge of all the physical forces in the Universe, a final theory of everything. But how could we ever know if what we call the theory of everything is a complete description of all that exists? We couldn’t, as this would assume we know all of physical reality, which is an impossibility. There could always be another force of nature, lurking in the shadows of our ignorance.

At the origin of the Universe, the very notion of cause and objectivity get entangled into a single unknowable, since we can’t possibly know the initial state of the Universe. We can, of course, construct models and test them against what we can measure of the Universe. But concordance is not a criterion for certainty. Different models may lead to the same concordance — the Universe we see — but we wouldn’t be able to distinguish between them since they come from an unknowable initial state. The first cause — the cause that must be uncaused and that unleashed all other causes — lies beyond the reach of scientific methodology as we know it. This doesn’t mean that we must invoke supernatural causes to fill the gap of our ignorance. A supernatural cause doesn’t explain in the way that scientific theories do; supernatural divine intervention is based on faith and not on data. It’s a personal choice, not a scientific one. It only helps those who believe.

Still, through a sequence of spectacular scientific discoveries, we have pieced together a cosmic history of exquisite detail and complexity. There are still many open gaps in our knowledge, and we shouldn’t expect otherwise. The next decades will see us making great progress in understanding many of the open cosmological questions of our time, such as the nature of dark matter and dark energy, and whether gravitational waves can tell us more about primordial inflation. But the problem of the first cause will remain open, as it doesn’t fit with the way we do science. This fact must, as Einstein wisely remarked, “fill a thinking person with a feeling of humility.” Not all questions need to be answered to be meaningful.

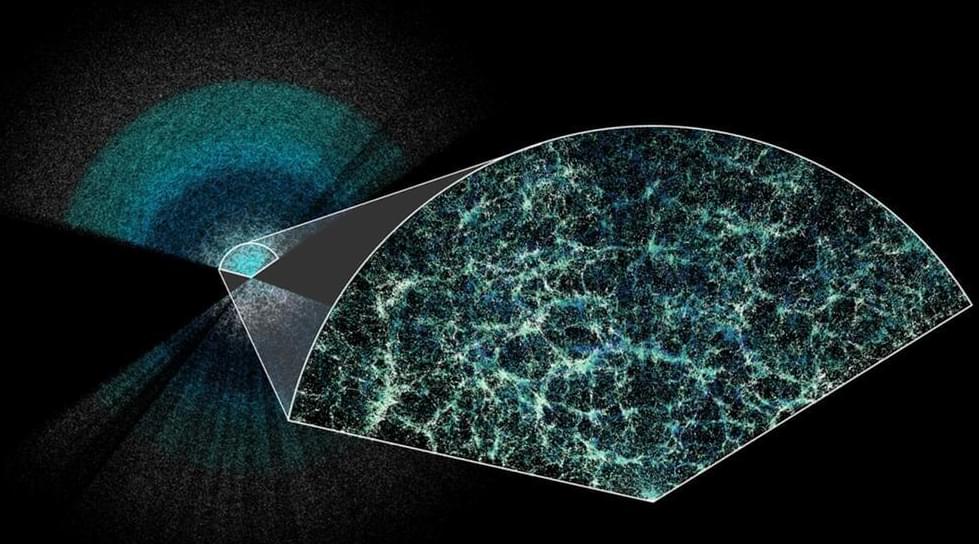

DESI Survey announces the most precise measurements of our expanding #universe using the BAO signal in 6.1 Million #galaxies and #Quasars from Year 1, tracing dark energy through cosmic time.

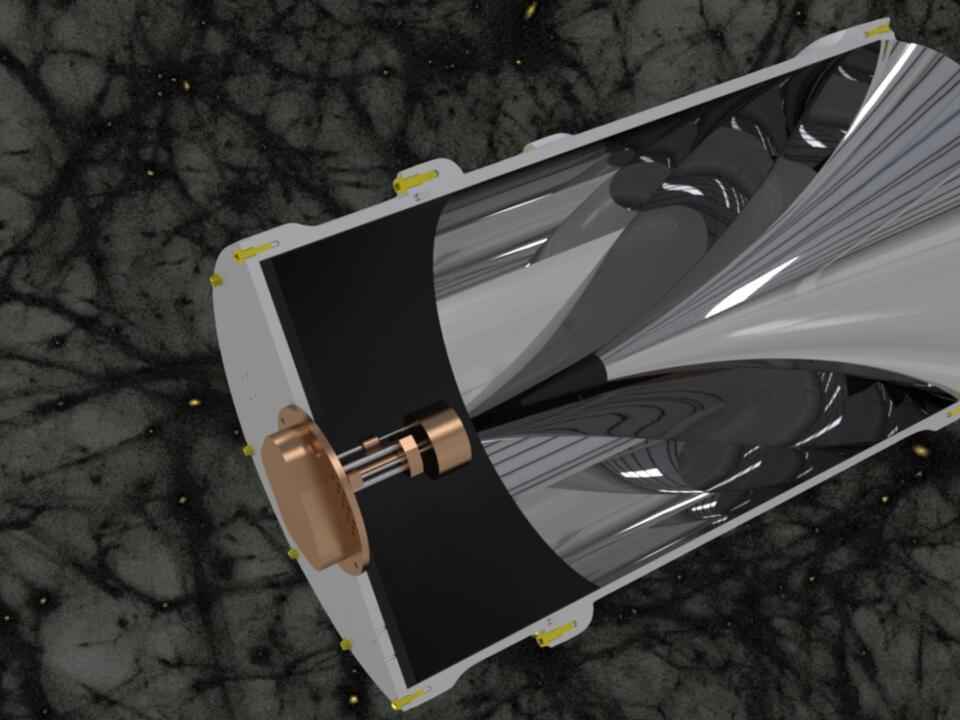

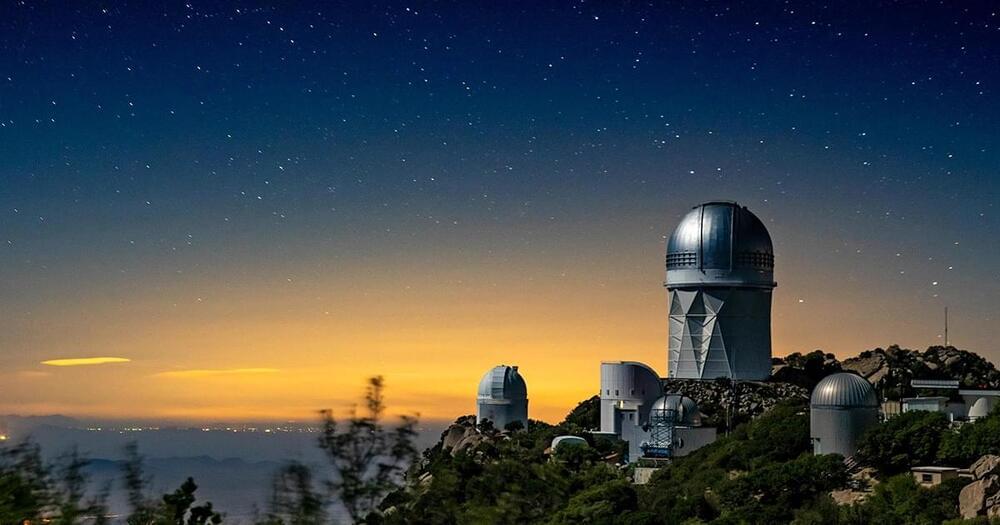

With 5,000 tiny robots in a mountaintop telescope, researchers can look 11 billion years into the past. The light from far-flung objects in space is just now reaching the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), enabling us to map our cosmos as it was in its youth and trace its growth to what we see today. Understanding how our universe has evolved is tied to how it ends, and to one of the biggest mysteries in physics: dark energy, the unknown ingredient causing our universe to expand faster and faster.

To study dark energy’s effects over the past 11 billion years, DESI has created the largest 3D map of our cosmos ever constructed, with the most precise measurements to date. This is the first time scientists have measured the expansion history of the young universe with a precision better than 1%, giving us our best view yet of how the universe evolved.

“Gravity pulls matter together, so that when we throw a ball in the air, the Earth’s gravity pulls it down toward the planet,” Mustapha Ishak-Boushaki, a professor of physics in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics (NSM) at UT Dallas, and member of the DESI collaboration, said in a statement. “But at the largest scales, the universe acts differently. It’s acting like there is something repulsive pushing the universe apart and accelerating its expansion. This is a big mystery, and we are investigating it on several fronts. Is it an unknown dark energy in the universe, or is it a modification of Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity at cosmological scales?”

DESI’s data, however, shows that the universe may have evolved in a way that isn’t quite consistent with the Lambda CDM model, indicating that the effects of dark energy on the universe may have changed since the early days of the cosmos.

“Our results show some interesting deviations from the standard model of the universe that could indicate that dark energy is evolving over time,” Ishak-Boushaki said. “The more data we collect, the better equipped we will be to determine whether this finding holds. With more data, we might identify different explanations for the result we observe or confirm it. If it persists, such a result will shed some light on what is causing cosmic acceleration and provide a huge step in understanding the evolution of our universe.”