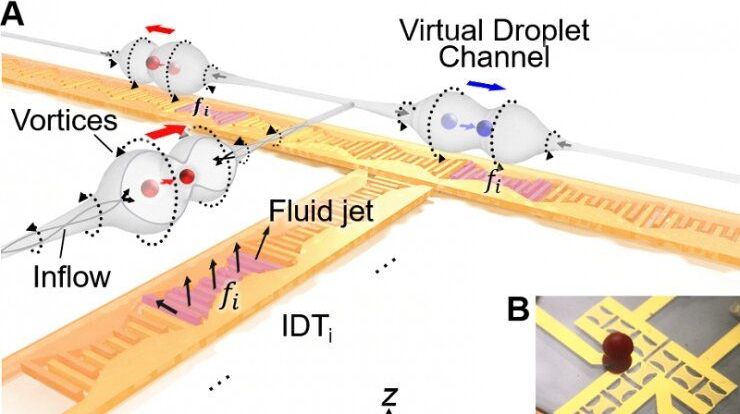

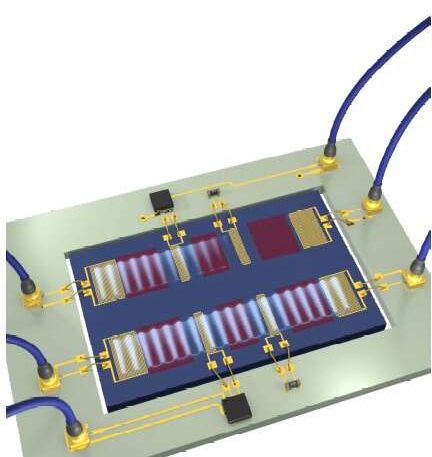

Engineers at Duke University have demonstrated a versatile microfluidic lab-on-a-chip that uses sound waves to create tunnels in oil to touchlessly manipulate and transport droplets. The technology could form the basis of a small-scale, programmable, rewritable biomedical chip that is completely reusable to enable on-site diagnostics or laboratory research.

The results appear online on June 10 in the journal Science Advances.

“Our new system achieves rewritable routing, sorting and gating of droplets with minimal external control, which are essential functions for the digital logic control of droplets,” said Tony Jun Huang, the William Bevan Distinguished Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science at Duke. “And we achieve it with less energy and a simpler setup that can control more droplets simultaneously than previous systems.”