Determine which video-level computer vision task you need to perform based on the insights you want to gain.

O,.o woah!

This instructs qsim to make use of its cuQuantum integration, which provides improved performance on NVIDIA GPUs. If you experience issues with this option, please file an issue on the qsim repository.

After you finish, don’t forget to stop or delete your VM on the Compute Instances dashboard to prevent further billing.

You are now ready to run your own large simulations on Google Cloud. For sample code of a large circuit, see the Simulate a large circuit tutorial.

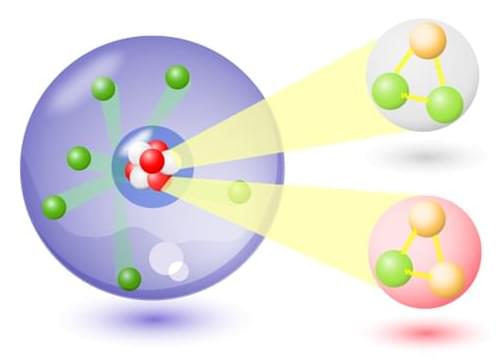

A team of researchers led by an Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC) faculty member performed the first-ever simulation of baryons—fundamental quantum particles—on a quantum computer.

With their results, the team has taken a step towards more complex quantum simulations that will allow scientists to study neutron stars, learn more about the earliest moments of the universe, and realize the revolutionary potential of quantum computers.

“This is an important step forward—it is the first simulation of baryons on a quantum computer ever,” Christine Muschik, an IQC faculty member, said. “Instead of smashing particles in an accelerator, a quantum computer may one day allow us to simulate these interactions that we use to study the origins of the universe and so much more.”

Cobalt has been getting a lot of attention lately because it is one of the most expensive materials found in lithium-ion batteries, which power everything from laptops and cell phones to electric vehicles. Cobalt extraction is largely concentrated in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where it is linked to human rights abuses and child labor, while cobalt refinement is almost exclusively done in China, making cobalt part of a tenuous supply chain. These are some of the reasons why battery manufacturers like Samsung and Panasonic and car makers like Tesla and VW, along with a number of startups are working to eliminate cobalt from lithium-ion batteries completely.

» Subscribe to CNBC: https://cnb.cx/SubscribeCNBC

» Subscribe to CNBC TV: https://cnb.cx/SubscribeCNBCtelevision.

» Subscribe to CNBC Classic: https://cnb.cx/SubscribeCNBCclassic.

About CNBC: From ‘Wall Street’ to ‘Main Street’ to award winning original documentaries and Reality TV series, CNBC has you covered. Experience special sneak peeks of your favorite shows, exclusive video and more.

Connect with CNBC News Online.

Get the latest news: https://www.cnbc.com/

Follow CNBC on LinkedIn: https://cnb.cx/LinkedInCNBC

Follow CNBC News on Facebook: https://cnb.cx/LikeCNBC

Follow CNBC News on Twitter: https://cnb.cx/FollowCNBC

Follow CNBC News on Instagram: https://cnb.cx/InstagramCNBC

#CNBC

How removing cobalt from batteries can make evs cheaper.

Apple has been talking for years about the role it wants to play in human health, led by the Apple Watch and its array of health-related features. With the Apple Watch maturing and Apple increasing its integration of health-focused hardware and software, several pieces of evidence suggest the company is positioning itself for an even bigger expansion in that direction.

According to trends compiled by Linkedin and seen by MacRumors, over the past year, Apple’s open job listings in health-related fields have increased by over 220%, with a significant portion of the increase coming in just the last several months. Apple’s health-focused hiring has been the fastest-growing segment for the company over the past year, followed most closely by sales and IT specialists, such as in cloud computing and security, according to the data.

Japanese startup Diver-X is looking to launch a SteamVR-compatible headset that seems to be taking a few ideas from popular anime Sword Art Online, which prominently features a fully immersive metaverse. While it’s not a brain-computer interface like the “full dive” NerveGear featured in the show, the heavy-weight hardware presents a pretty interesting approach to VR headset design.

Called HalfDive, the Tokyo-based company says its taking advantage of the sleeping position to “enabl[e] human activity in its lowest energetic state.”

Since it’s worn laying down, the creators say they’re freed from many of the design constraints that conventional VR headset makers are used to pursuing with the introduction of things like pancake optics and microdisplays. Since the weight isn’t on your neck, it doesn’t have to be light or slim.

Yekaterina “Kate” Shulgina was a first year student in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, looking for a short computational biology project so she could check the requirement off her program in systems biology. She wondered how genetic code, once thought to be universal, could evolve and change.

That was 2016 and today Shulgina has come out the other end of that short-term project with a way to decipher this genetic mystery. She describes it in a new paper in the journal eLife with Harvard biologist Sean Eddy.

The report details a new computer program that can read the genome sequence of any organism and then determine its genetic code. The program, called Codetta, has the potential to help scientists expand their understanding of how the genetic code evolves and correctly interpret the genetic code of newly sequenced organisms.