🏅 R&D 100 Award Winner 🏅

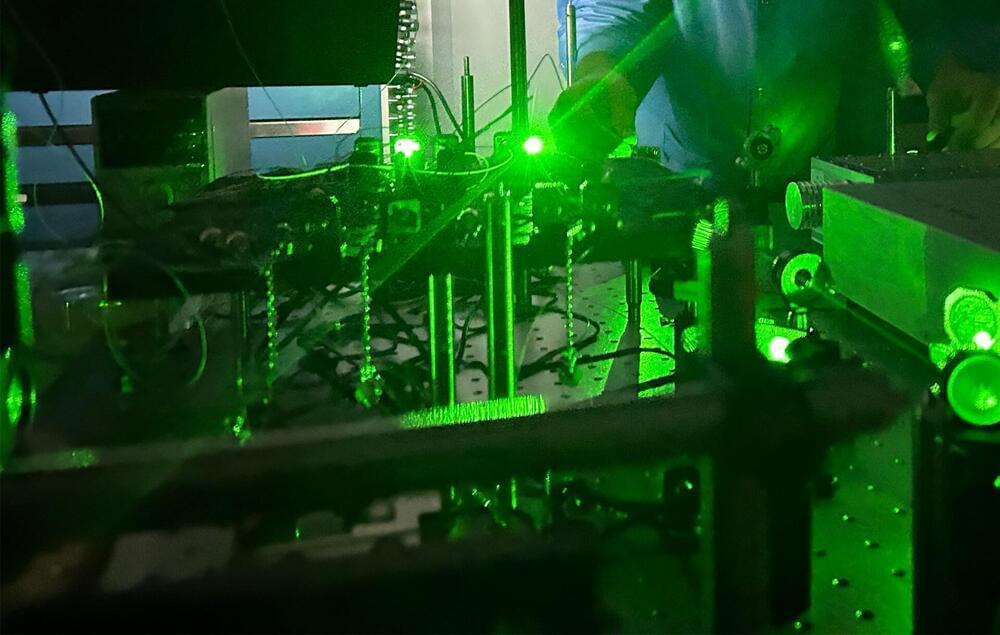

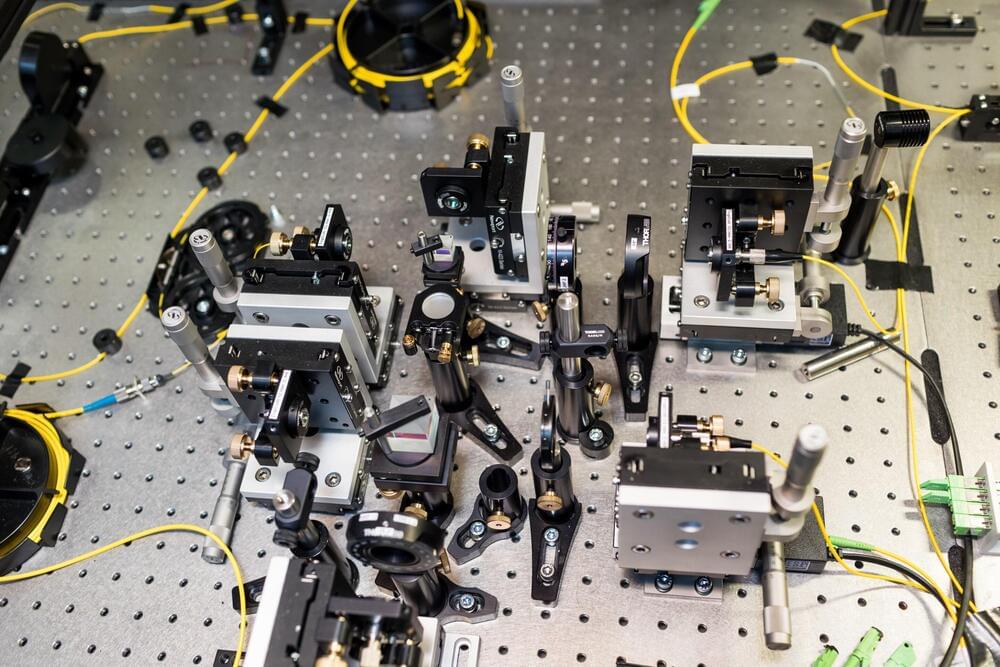

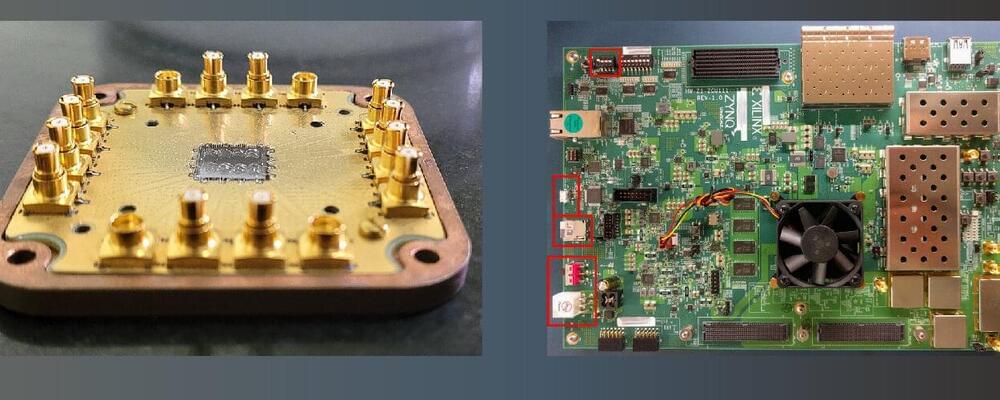

The Noncontact Laser Ultrasound (NCLUS) is a portable laser-based system that acquires ultrasound images of human tissue without touching a patient. It offers capabilities comparable to those of an MRI and CT but at vastly lower cost in an automated and portable platform.

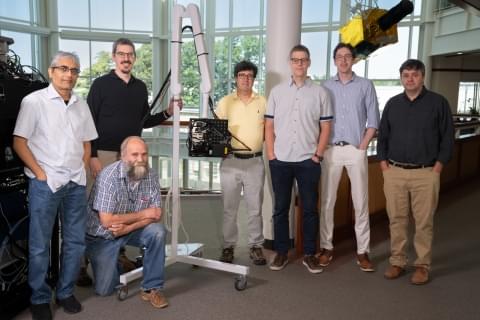

In addition to receiving an R&D 100 Award, NCLUS received the Silver Medal in the Special Recognition: Market Disruptor Products category. Congratulations to the NCLUS team!

Researchers from MIT Lincoln Laboratory and their collaborators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Ultrasound Research and Translation (CURT) have developed a new medical imaging device: the Noncontact Laser Ultrasound (NCLUS). This laser-based ultrasound system provides images of interior body features such as organs, fat, muscle, tendons, and blood vessels. The system also measures bone strength and may have the potential to track disease stages over time.

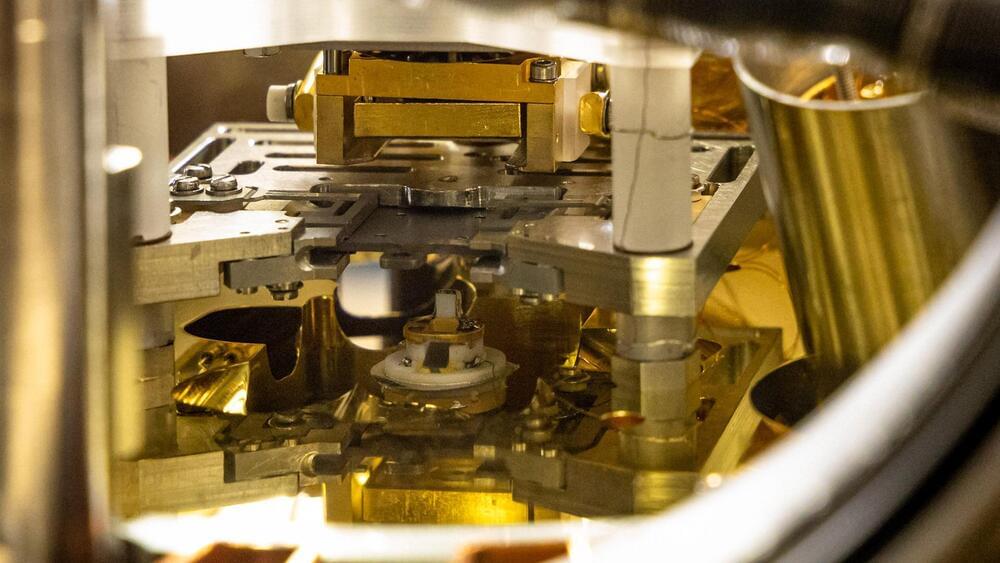

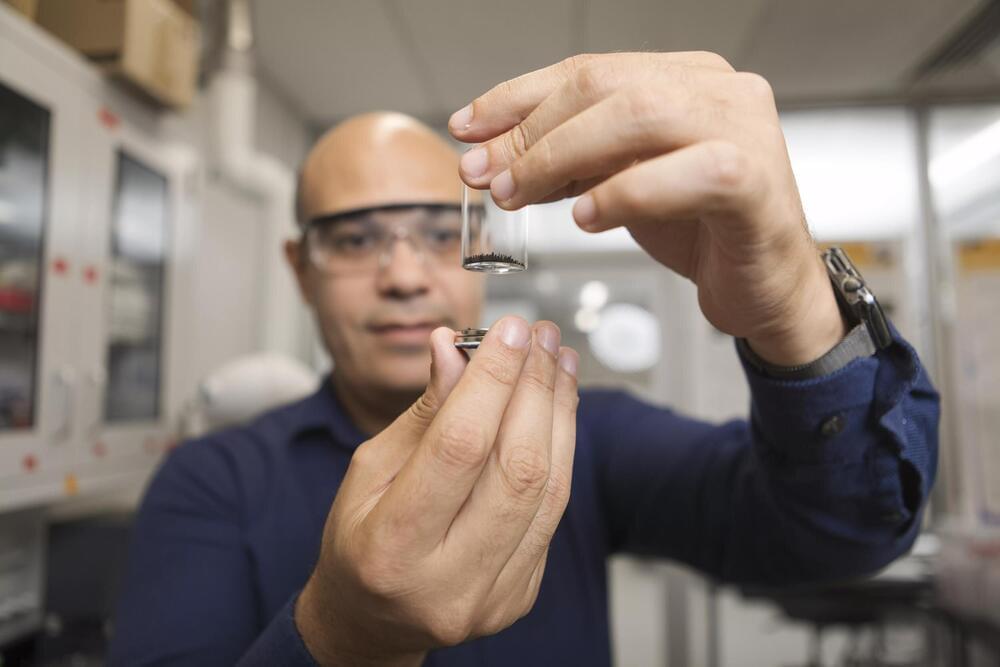

“Our patented skin-safe laser system concept seeks to transform medical ultrasound by overcoming the limitations associated with traditional contact probes,” explains principal investigator Robert Haupt, a senior staff member in Lincoln Laboratory’s Active Optical Systems Group. Haupt and senior staff member Charles Wynn are co-inventors of the technology, with assistant group leader Matthew Stowe providing technical leadership and oversight of the NCLUS program. Rajan Gurjar is the system integrator lead, with Jamie Shaw, Bert Green, Brian Boitnott (now at Stanford University), and Jake Jacobsen collaborating on optical and mechanical engineering and construction of the system.

Medical ultrasound in practice