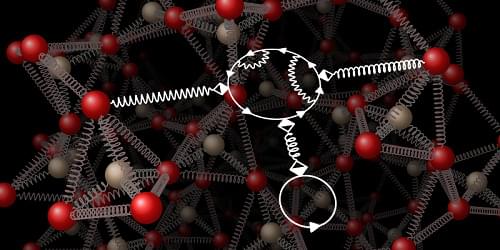

A new set of equations captures the dynamical interplay of electrons and vibrations in crystals and forms a basis for computational studies.

Although a crystal is a highly ordered structure, it is never at rest: its atoms are constantly vibrating about their equilibrium positions—even down to zero temperature. Such vibrations are called phonons, and their interaction with the electrons that hold the crystal together is partly responsible for the crystal’s optical properties, its ability to conduct heat or electricity, and even its vanishing electrical resistance if it is superconducting. Predicting, or at least understanding, such properties requires an accurate description of the interplay of electrons and phonons. This task is formidable given that the electronic problem alone—assuming that the atomic nuclei stand still—is already challenging and lacks an exact solution. Now, based on a long series of earlier milestones, Gianluca Stefanucci of the Tor Vergata University of Rome and colleagues have made an important step toward a complete theory of electrons and phonons [1].

At a low level of theory, the electron–phonon problem is easily formulated. First, one considers an arrangement of massive point charges representing electrons and atomic nuclei. Second, one lets these charges evolve under Coulomb’s law and the Schrödinger equation, possibly introducing some perturbation from time to time. The mathematical representation of the energy of such a system, consisting of kinetic and interaction terms, is the system’s Hamiltonian. However, knowing the exact theory is not enough because the corresponding equations are only formally simple. In practice, they are far too complex—not least owing to the huge number of particles involved—so that approximations are needed. Hence, at a high level, a workable theory should provide the means to make reasonable approximations yielding equations that can be solved on today’s computers.