Femoral head avascular necrosis (AVN) is a debilitating condition that prevents the thighbone from repairing itself at the portion closest to the hip, leading to possible collapse.

In a new study in Arthoplasty Today, a team including Yale Department of Orthopaedics & Rehabilitation’s Daniel Wiznia,…

In a paper published in the journal Arthroplasty Today, Daniel Wiznia, MD, assistant professor of orthopaedics & rehabilitation and co-director of Yale Medicine’s Avascular Necrosis Program, presents a new surgical technique designed to prevent or delay hip collapse in patients with femoral head avascular necrosis (AVN). Thanks to 3D innovations and novel applications of intraoperative navigation technology developed at Yale, Wiznia is leading a multidisciplinary approach to optimizing clinical outcomes.

Femoral AVN, otherwise known as osteonecrosis, is a debilitating condition associated with compromised blood supply to the portion of the thighbone closest to the hip. It particularly impacts the head of the bone. When the small vessels there are injured, the bone can no longer repair itself. Upwards of 20,000 new cases of femoral AVN are diagnosed each year in the United States, and those with the condition face a range of potential complications, such as collapse of the femoral head.

AVN is commonly diagnosed in people between the ages of 30 and 65. For some patients, there are no symptoms, which results in the condition being discovered incidentally. Up to 67 percent of patients with femoral AVN progress to symptomatic disease. A total hip arthroplasty (THA), otherwise known as a total hip replacement, is the current best treatment when the femoral head ultimately collapses. However, THA in younger patients has an increased risk of mechanical failure due to a higher level of physical activity and the length of time that the hip implant will be utilized. Therefore, there is a need for therapeutic strategies that effectively delay and prevent hip collapse, reducing the likelihood of requiring a THA.

/ anastasiintech Support me at Patreon ➜

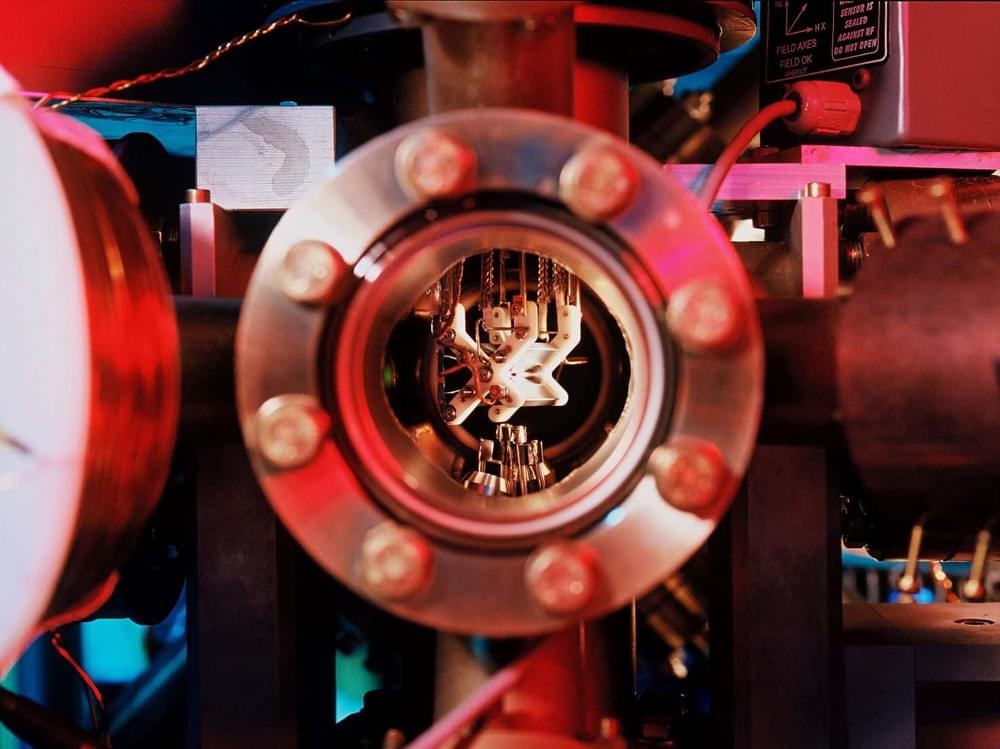

/ anastasiintech Sign up for my Deep In Tech Newsletter for free! ➜ https://anastasiintech.substack.com Timestamps: 00:00 — Intro 03:16 — Lithium Niobate 05:56 — How does this chip work? 08:23 — Critics.