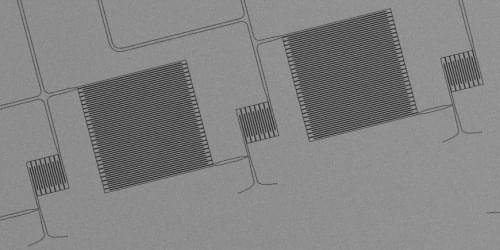

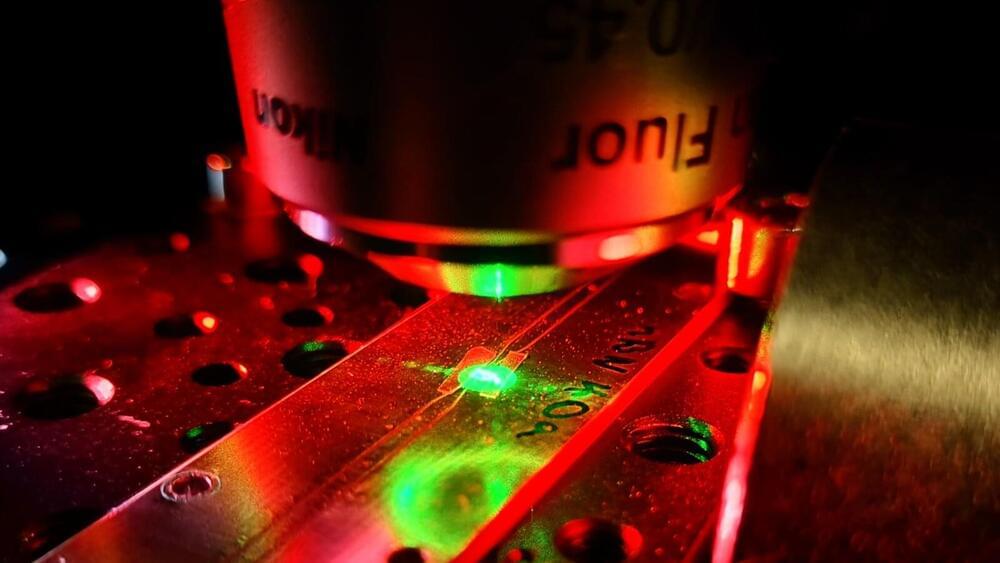

Single-photon detectors built from superconducting nanowires have become a vital tool for quantum information processing, while their superior speed and sensitivity have made them an appealing option for low-light imaging applications such as space exploration and biophotonics. However, it has proved difficult to build high-resolution cameras from these devices because the cryogenically cooled detectors must be connected to readout electronics operating at room temperature. Now a research team led by Karl Berggren at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has demonstrated a superconducting electronics platform that can process the single-photon signals at ultracold temperatures, providing a scalable pathway for building megapixel imaging arrays [1].

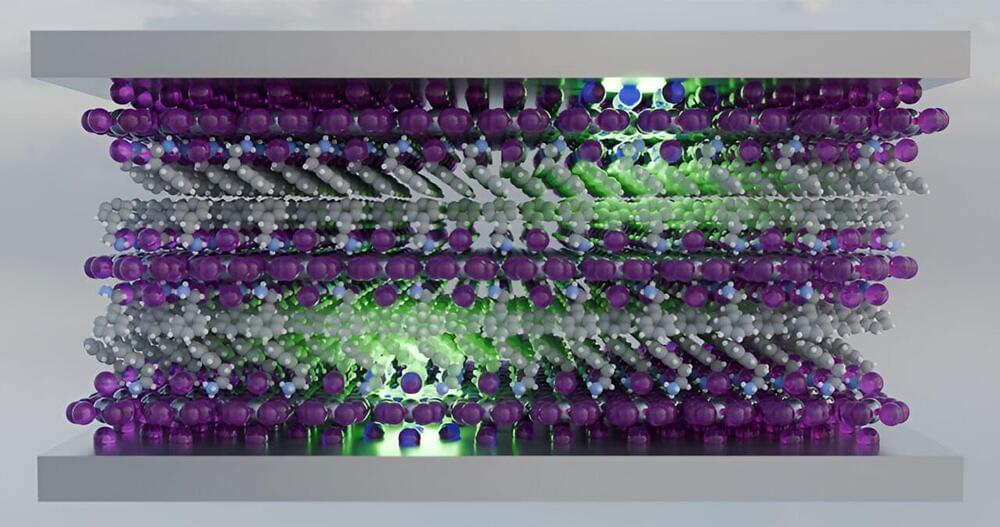

The key problem with designing high-resolution cameras based on these superconducting detectors is that each of the sensors requires a dedicated readout wire to record the single-photon signals, which adds complexity and heat load to the cryogenic system. Researchers have explored various multiplexing techniques to reduce the number of connections to individual detectors, yielding imaging arrays in the kilopixel range, but further scaling will likely require a signal-processing solution that can operate at ultralow temperatures.

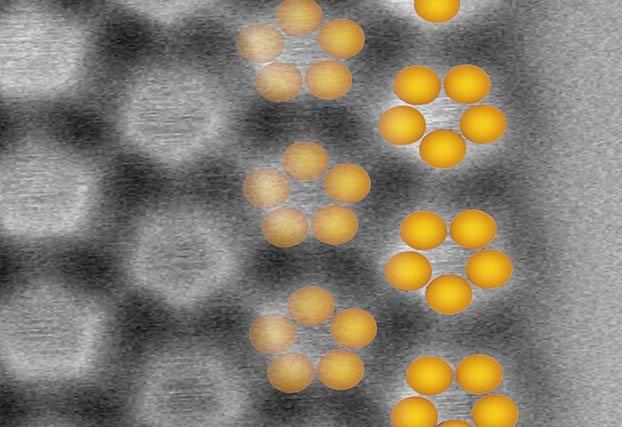

Berggren and his collaborators believe that the answer lies in devices called nanocryotrons (nTrons), which are three-terminal structures made from superconducting nanowires, just like the single-photon detectors are. Although nTrons do not deliver the same speed and power of superconducting electronics based on Josephson junctions, the researchers argue that these shortcomings are not a critical problem in photon-sensing applications, where the detectors are similarly limited in speed and power. The nTrons also offer several advantages over Josephson junctions: they operate over a wider range of cryogenic temperatures, they don’t require magnetic shielding, and they exploit the same fabrication process as that used for the detectors, allowing for easy on-chip integration.