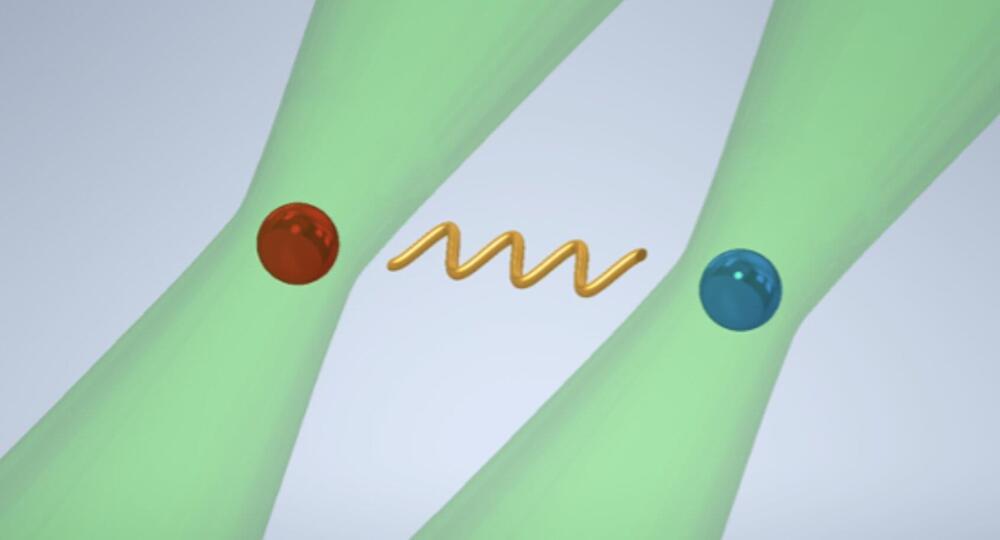

Symmetry plays a crucial role in understanding fundamental phenomena such as conservation laws, the classification of phases of matter, and their transitions. Recently, researchers have been exploring ways to manipulate symmetries in quantum many-body systems with time-dependent driving protocols and, in particular, engineering new symmetries that do not naturally occur. This significantly enriches the toolbox for quantum simulation and computation, and has led to many exciting discoveries of nonequilibrium phases such as discrete time crystals. However, controlling multiple symmetries—especially in a simple and experimentally friendly way—has remained a challenge. In this work, we propose a novel method to engineer hierarchical symmetries by time-dependent protocols.

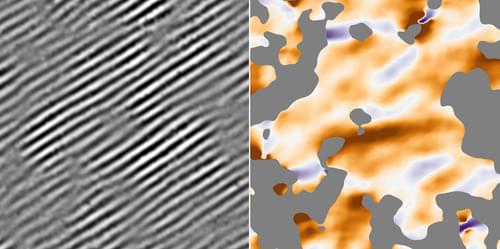

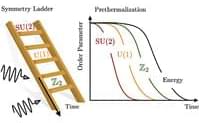

By carefully controlling how symmetry-indicating observables evolve over time, we show how to create a sequence of symmetries that emerge one after another, each with distinct properties. Our method relies on a recursive construction that hierarchically minimizes the effects of symmetry-breaking processes. This leads to a corresponding sequence of prethermal steady states with controllable lifetimes, each exhibiting a lower symmetry than the preceding one. We illustrate this protocol with several examples, demonstrating how different types of order can emerge through hierarchical symmetry breaking.

This toolbox of hierarchical symmetries opens a new path to stabilizing quantum states and controlling unwanted symmetry-breaking effects, which can be particularly useful in quantum computing and quantum simulation. The construction applies to classical and quantum, fermionic and bosonic, interacting and noninteracting systems. The underlying mechanism generalizes state-of-the-art dynamical decoupling techniques and is implementable on present-day quantum simulation platforms.