Cancer creates an immunosuppressive environment that hampers immune responses, allowing tumors to grow and resist therapy. One way the immune system fights back is by inducing ferroptosis, a type of cell death, in tumor cells through CD8 + T cells. This involves lipid peroxidation and enzymes like lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (Lpcat3), which makes cells more prone to ferroptosis. However, the mechanisms by which cancer cells avoid immunotherapy-mediated ferroptosis are unclear. Our study reveals how cancer cells evade ferroptosis and anti-tumor immunity through the upregulation of fatty acid-binding protein 7 (Fabp7).

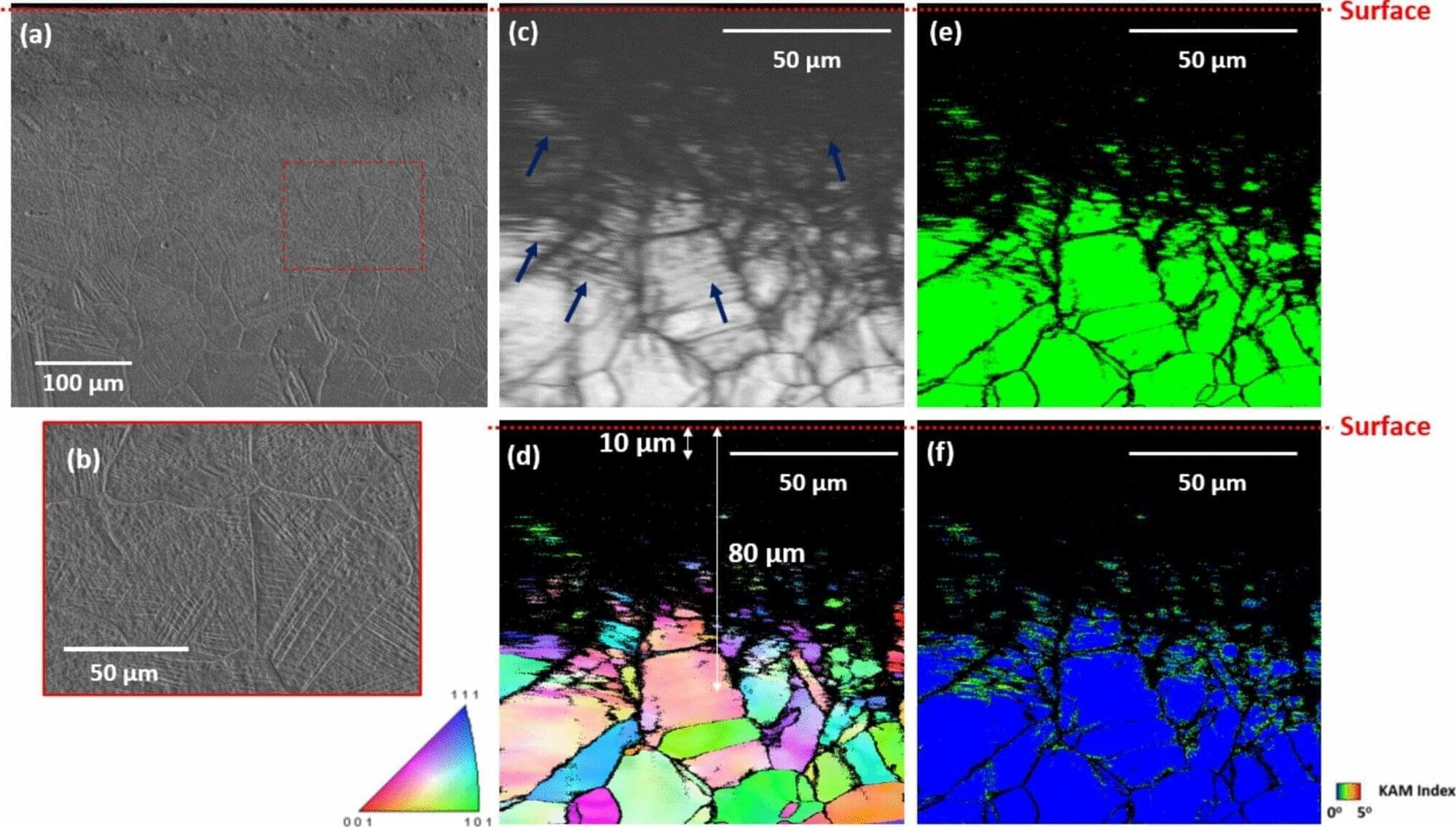

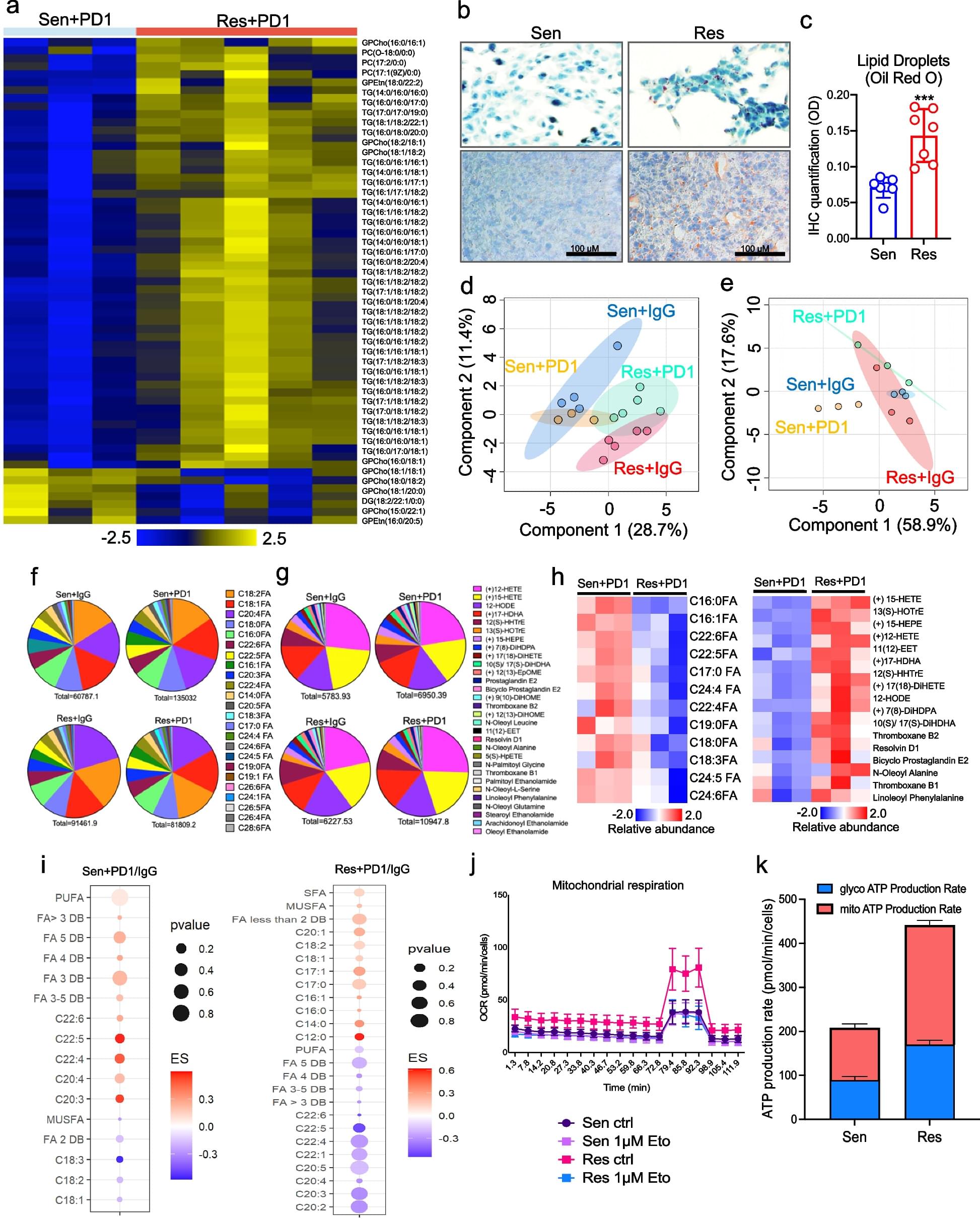

To explore how cancer cells resist immune cell-mediated ferroptosis, we used a comprehensive range of techniques. We worked with cell lines including PD1-sensitive, PD1-resistant, B16F10, and QPP7 glioblastoma cells, and conducted in vivo studies in syngeneic 129 Sv/Ev, C57BL/6, and conditional knockout mice with Rora deletion specifically in CD8+ T cells, Cd8 cre; Rorafl mice. Methods included mass spectrometry-based lipidomics, targeted lipidomics, Oil Red O staining, Seahorse analysis, quantitative PCR, immunohistochemistry, PPARγ transcription factor assays, ChIP-seq, untargeted lipidomic analysis, ROS assay, ex vivo co-culture of CD8+ T cells with cancer cells, ATAC-seq, RNA-seq, Western blotting, co-immunoprecipitation assay, flow cytometry and Imaging Mass Cytometry.

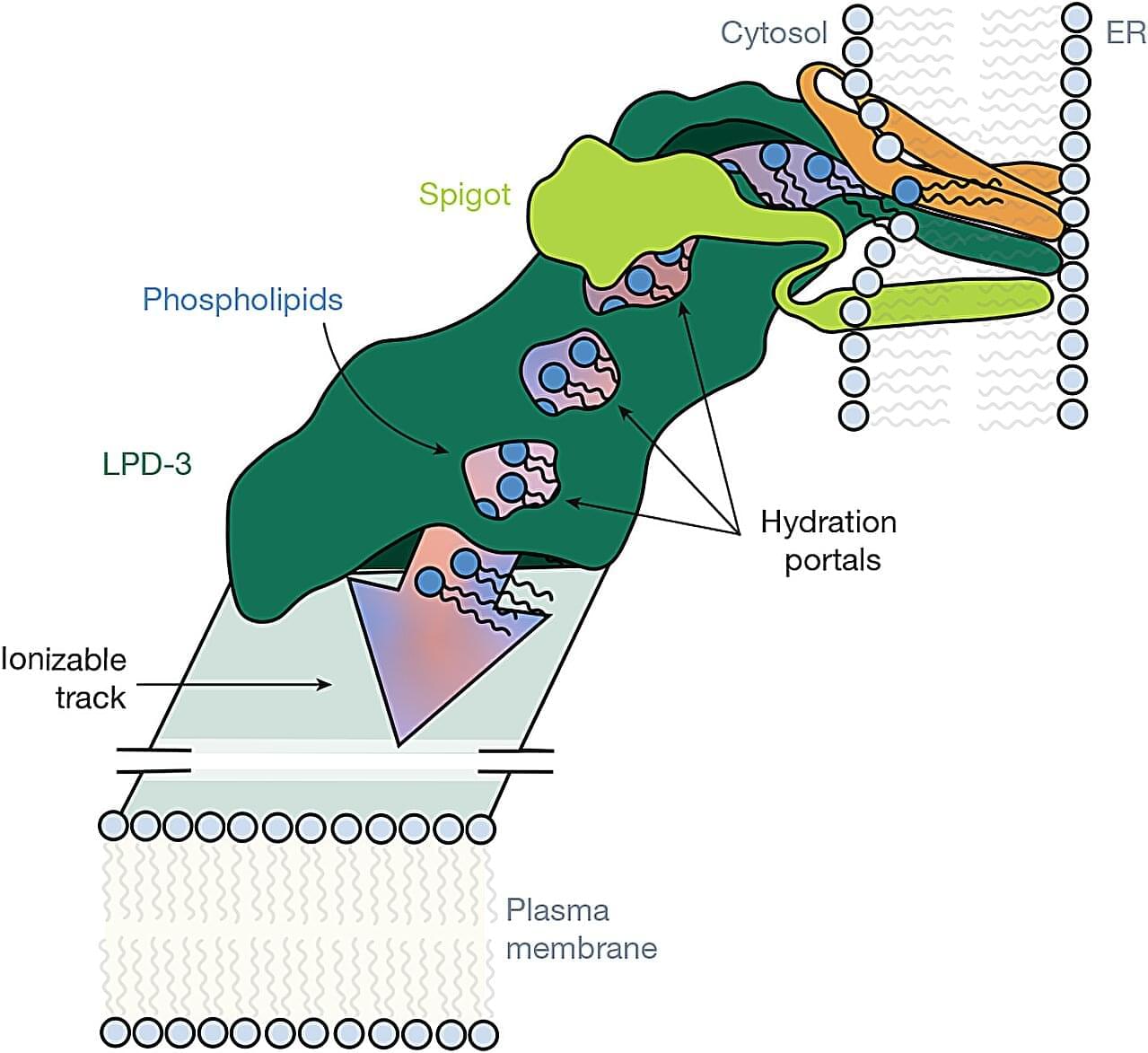

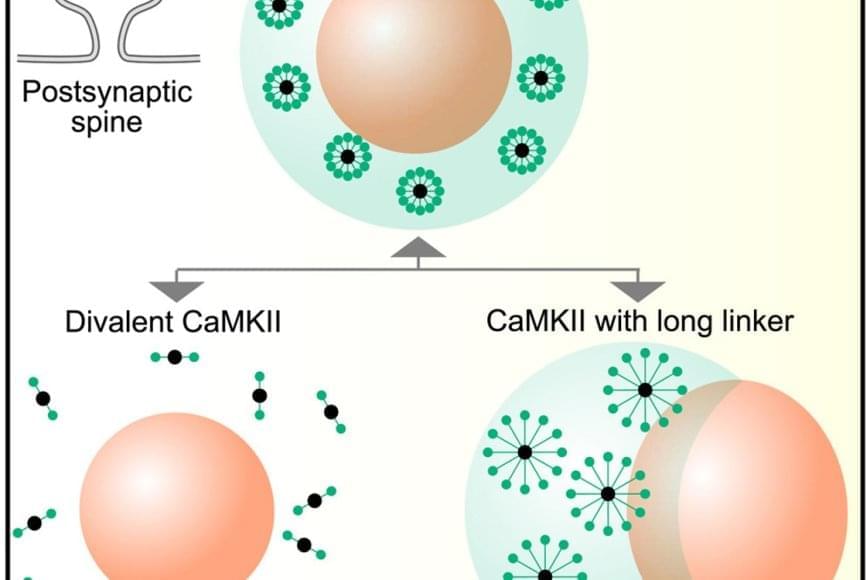

PD1-resistant tumors upregulate Fabp7, driving protective metabolic changes that shield cells from ferroptosis and evade anti-tumor immunity. Fabp7 decreases the transcription of ferroptosis-inducing genes like Lpcat3 and increases the transcription of ferroptosis-protective genes such as Bmal1 through epigenetic reprogramming. Lipidomic profiling revealed that Fabp7 increases triglycerides and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), which impede lipid peroxidation and ROS generation. Fabp7 also improves mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation (FAO), enhancing cancer cell survival. Furthermore, cancer cells increase Fabp7 expression in CD8+ T cells, disrupting circadian clock gene expression and triggering apoptosis through p53 stabilization. Clinical trial data revealed that higher FABP7 expression correlates with poorer overall survival and progression-free survival in patients undergoing immunotherapy.