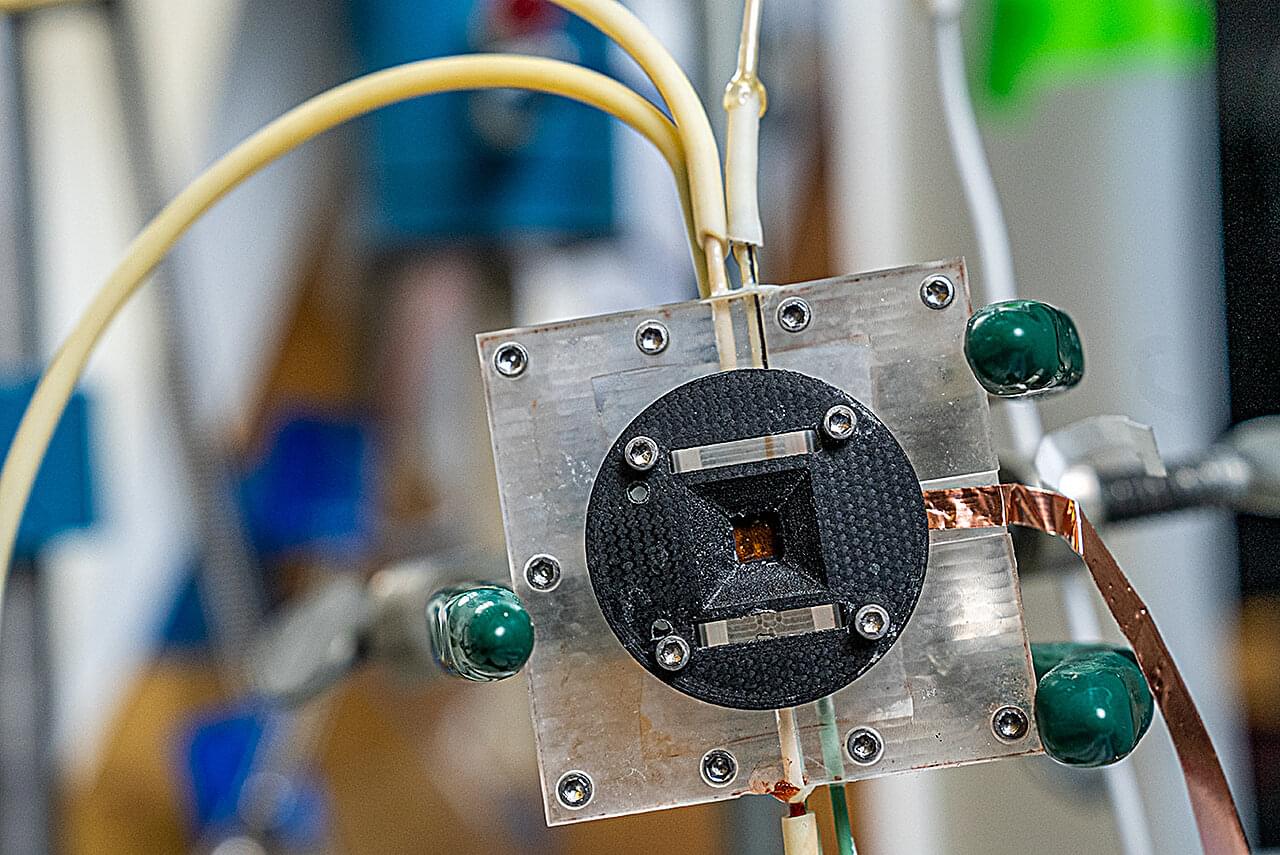

Electrolyzers are devices that can split water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity and via a process known as electrolysis. In the future, these devices could help to produce hydrogen gas from water, which is valuable for a wide range of applications and could also be used to power fuel cells and decarbonize energy systems.

At the core of the water electrolysis process are electrochemical reactions known as hydrogen evolution reactions (HERs). In basic (i.e., alkaline) conditions, these reactions tend to be slow, which in turn hinders the performance of electrolyzers.

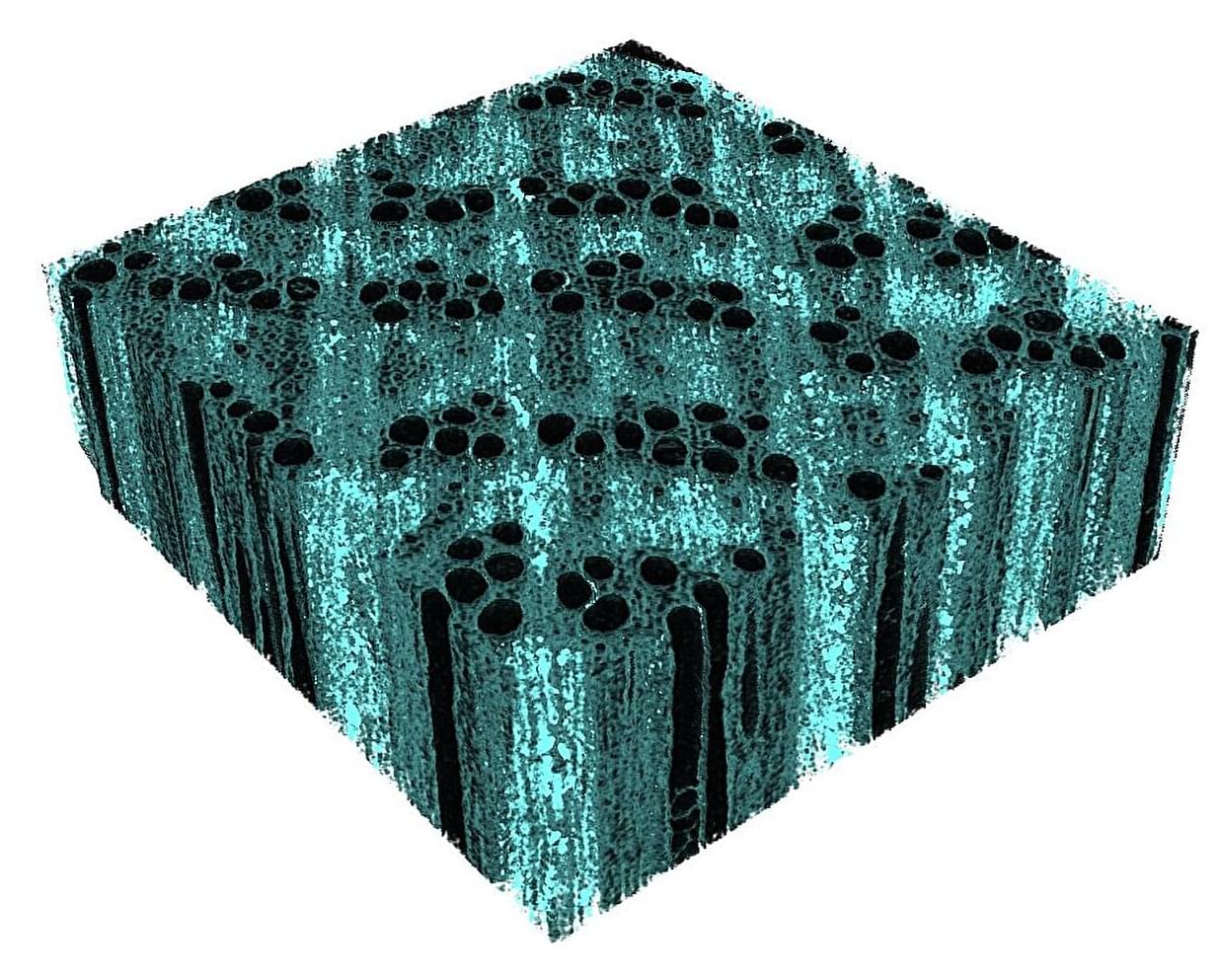

In recent years, energy researchers have been trying to design new electrode-aqueous interfaces or identify new catalysts that could speed up HERs and thus enhance the ability of electrolyzers to produce hydrogen. One of the HER catalysts most employed to date is platinum, yet its performance is limited by a process known as hydrogen binding. This process entails the strong adherence of hydrogen atoms to its surface, which can block reaction sites and slow down HERs.