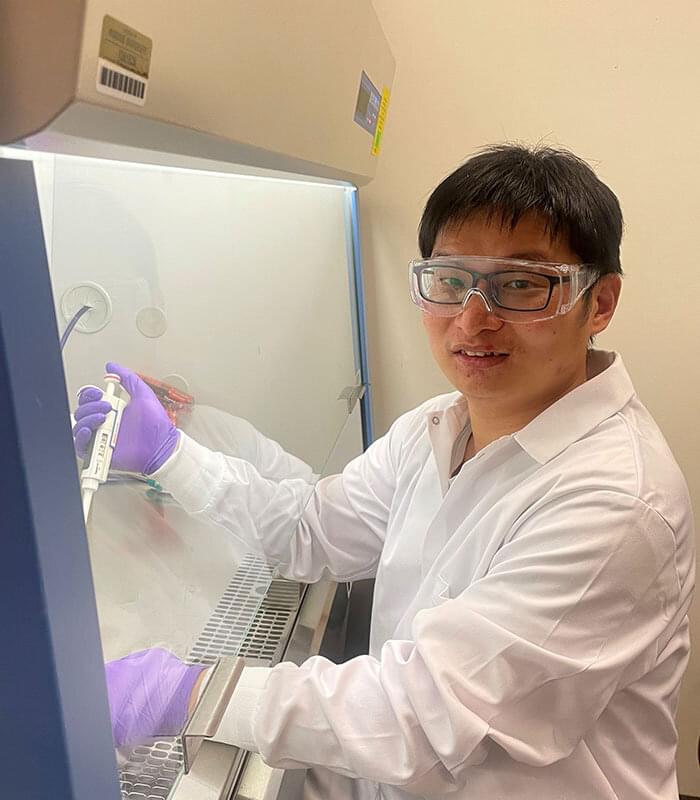

A Purdue University chemical engineer has improved upon traditional methods to produce off-the-shelf human immune cells that show strong antitumor activity, according to a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Cell Reports.

Xiaoping Bao, a Purdue University assistant professor from the Davidson School of Chemical Engineering, said CAR-neutrophils, or chimeric antigen receptor neutrophils, and engraftable HSCs, or hematopoietic stem cells, are effective types of therapies for blood diseases and cancer. Neutrophils are the most abundant white cell blood type and effectively cross physiological barriers to infiltrate solid tumors. HSCs are specific progenitor cells that will replenish all blood lineages, including neutrophils, throughout life.

“These cells are not readily available for broad clinical or research use because of the difficulty to expand ex vivo to a sufficient number required for infusion after isolation from donors,” Bao said. “Primary neutrophils especially are resistant to genetic modification and have a short half-life.”