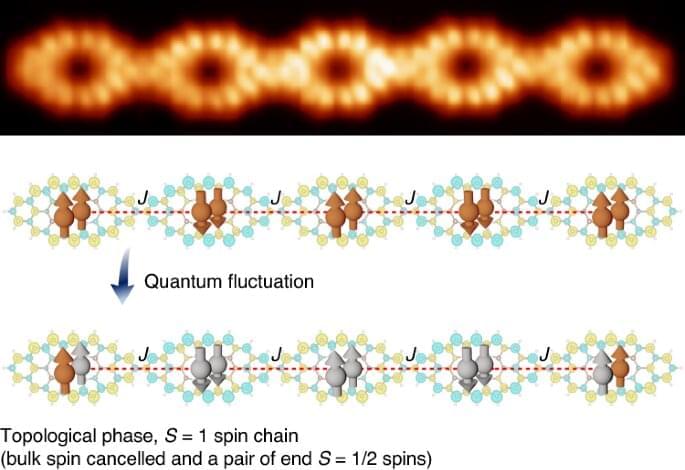

Topological materials are a special kind of material that have different functional properties on their surfaces than on their interiors. One of these properties is electrical. These materials have the potential to make electronic and optical devices much more efficient or serve as key components of quantum computers. But recent theories and calculations have shown that there can be thousands of compounds that have topological properties, and testing all of them to determine their topological properties through experiments will take years of work and analysis. Hence, there is a dire need for faster methods to test and study topological materials.

A team of researchers from MIT, Harvard University, Princeton University, and Argonne National Laboratory proposed a new approach that is faster at screening the candidate materials and can predict with more than 90 percent accuracy whether a material is topological or not. The traditional way of solving this problem is quite complicated and can be explained as follows: Firstly, a method called density functional theory is used to perform initial calculations, which are then followed by complex experiments that involve cutting a piece of material to atomic-level flatness and probing it with instruments under high vacuum.

The new proposed method is based on how the material absorbs X-rays, which is different from the old methods, which were based on photoemissions or tunneling electrons. There are certain significant advantages to using X-ray absorption data, which can be listed as follows: Firstly, there is no requirement for expensive lab apparatus. X-ray absorption spectrometers are used, which are readily available and can work in a typical environment, hence the low cost of setting up an experiment. Secondly, such measurements have already been done in chemistry and biology for other applications, so the data is already available for numerous materials.