If smoke indicates a fire, nitric oxide signals inflammation. The chemical mediator promotes inflammation, but researchers suspect it can do its job too well after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures and related injuries and initiate early onset osteoarthritis. Typically, the degenerative disease is only diagnosed after progressive symptoms, but it potentially could be identified much earlier through nitric oxide monitoring, according to Huanyu “Larry” Cheng, James E. Henderson Jr. Memorial Associate Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics at Penn State.

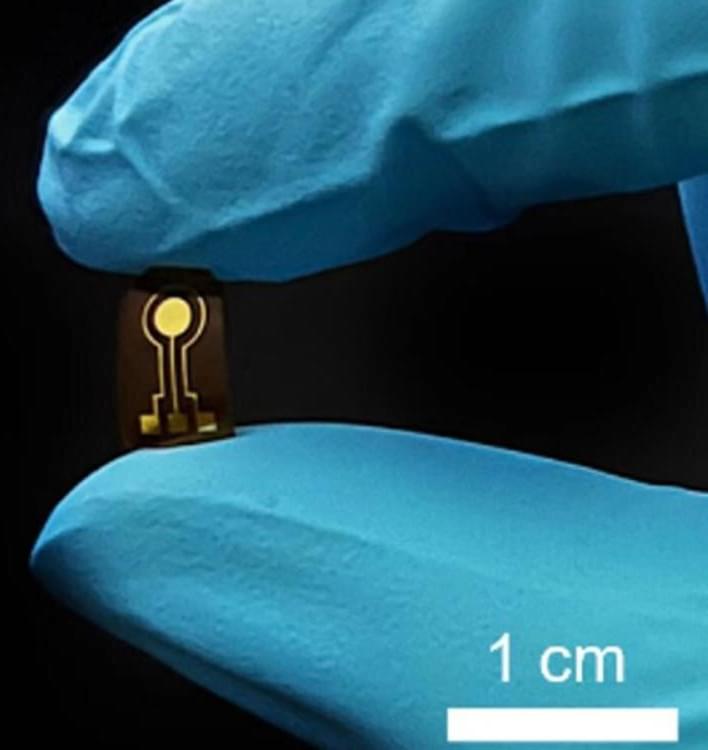

Cheng and his student, Shangbin Liu, who earned a master’s degree in engineering science and mechanics at Penn State this year, collaborated with researchers based in China to develop a flexible biosensor capable of continuous and wireless nitric oxide detection in rabbits. They published their approach in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Real-time assessment of biomarkers associated with inflammation, such as nitric oxide in the joint cavity, could indicate pathological evolution at the initial development of osteoarthritis, providing essential information to optimize therapies following traumatic knee injury,” Cheng said.