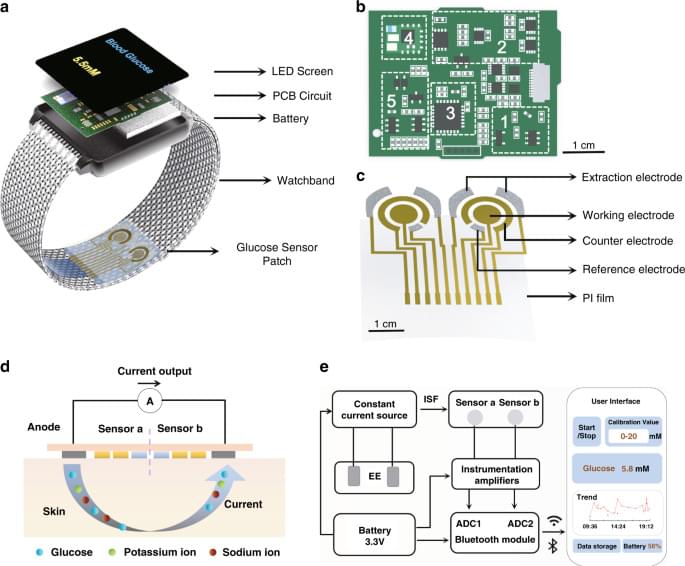

This article reports a highly integrated watch for noninvasive continual blood glucose monitoring. The watch employs a Nafion-coated flexible electrochemical sensor patch fixed on the watchband to obtain interstitial fluid (ISF) transdermally at the wrist. This reverse iontophoresis-based extraction method eliminates the pain and inconvenience that traditional fingerstick blood tests pose in diabetic patients’ lives, making continual blood glucose monitoring practical and easy. All electronic modules, including a rechargeable power source and other modules for signal processing and wireless transmission, are integrated onto a watch face-sized printed circuit board (PCB), enabling comfortable wearing of this continual glucose monitor. Real-time blood glucose levels are displayed on the LED screen of the watch and can also be checked with the smartphone user interface.