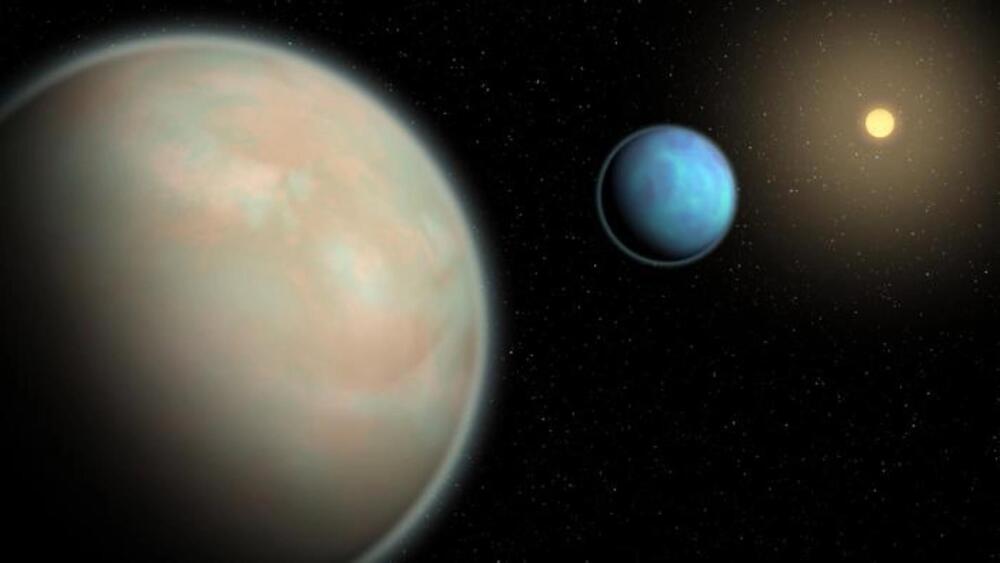

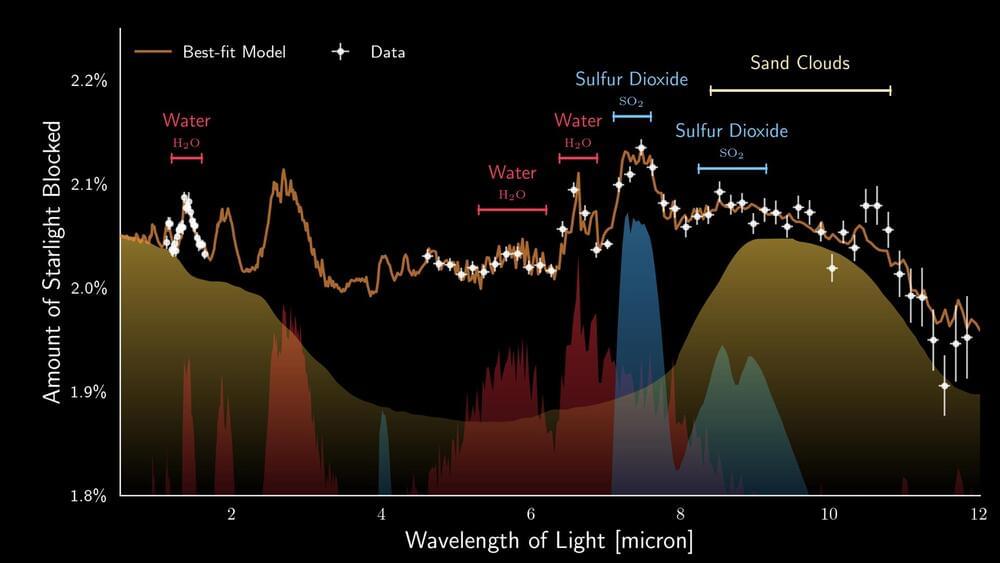

European astronomers, co-led by researchers from the Institute of Astronomy, KU Leuven, used recent observations made with the James Webb Space Telescope to study the atmosphere of the nearby exoplanet WASP-107b. Peering deep into the fluffy atmosphere of WASP-107b they discovered not only water vapour and sulfur dioxide, but even silicate sand clouds. These particles reside within a dynamic atmosphere that exhibits vigorous transport of material.

Astronomers worldwide are harnessing the advanced capabilities of the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) aboard the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to conduct groundbreaking observations of exoplanets – planets orbiting stars other than our own Sun. One of these fascinating worlds is WASP-107b, a unique gaseous exoplanet that orbits a star slightly cooler and less massive than our Sun. The mass of the planet is similar to that of Neptune but its size is much larger than that of Neptune, almost approaching the size of Jupiter. This characteristic renders WASP-107b rather ‘fluffy’ when compared to the gas giant planets within our solar system. The fluffiness of this exoplanet enables astronomers to look roughly 50 times deeper into its atmosphere compared to the depth of exploration achieved for a solar-system giant like Jupiter.

The team of European astronomers took full advantage of the remarkable fluffiness of this exoplanet, enabling them to look deep into its atmosphere. This opportunity opened a window into unravelling the complex chemical composition of its atmosphere. The reason behind this is quite straightforward: the signals, or spectral features, are far more prominent in a less dense atmosphere compared to a more compact one. Their recent study, now published in Nature, reveals the presence of water vapour, sulfur dioxide (SO2), and silicate clouds, but notably, there is no trace of the greenhouse gas methane (CH4).