Link :

Imagine a world where cancer treatment doesn’t rely on harsh chemicals or debilitating side effects, but instead harnesses a natural defense mechanism embedded in every cell of our bodies. Recent breakthroughs by scientists at Northwestern University suggest this may soon be a reality. They’ve uncovered a “kill switch” that could change everything we know about cancer treatment, offering a new path that sidesteps the harmful impacts of chemotherapy. But how does this hidden code work, and could it truly offer a more effective way to fight cancer?

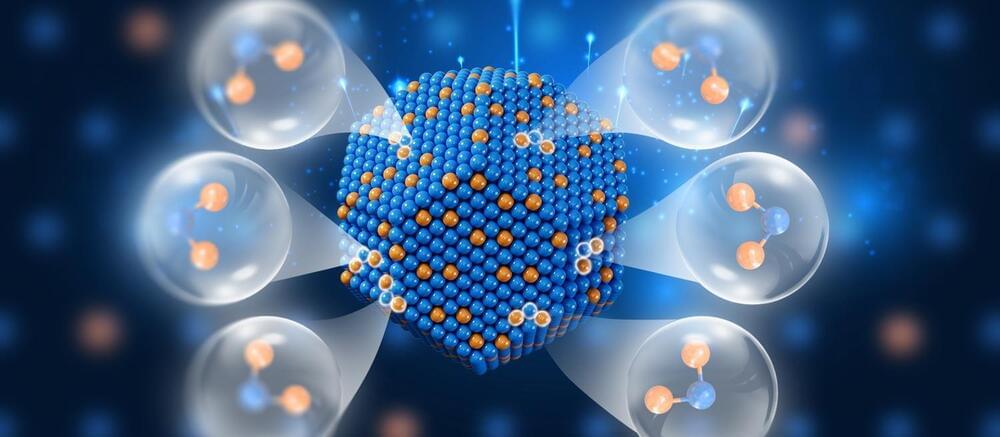

Northwestern University scientists have uncovered a powerful “kill switch” embedded in every cell of the body, which may provide a natural defense mechanism against cancer. This kill switch operates using small RNA molecules, known as microRNAs, and large protein-coding RNAs that trigger cell self-destruction when they detect signs of cancer. The key discovery is that these molecules can effectively induce cancer cell death without allowing the cancer to develop resistance, a significant advantage over traditional chemotherapy.

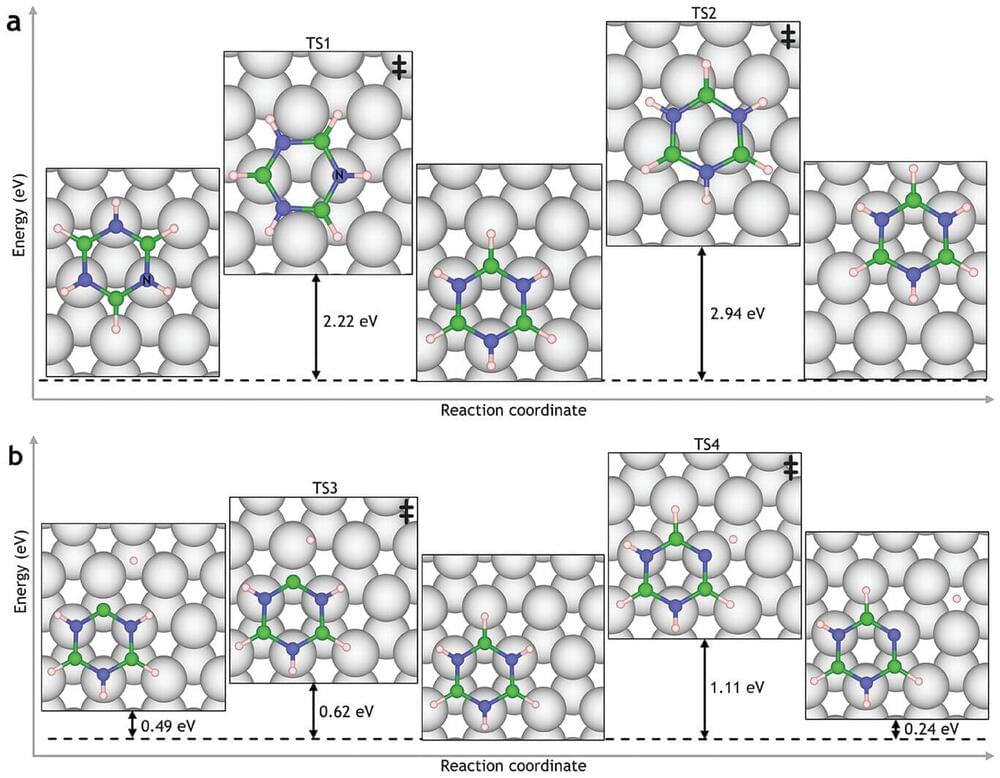

The microRNAs use a mechanism called DISE (Death Induced by Survival gene Elimination) to initiate cancer cell death. DISE works by eliminating multiple genes essential for cancer cell survival, making it impossible for the cells to adapt or become resistant. Researchers found that the most effective microRNAs contain a specific sequence of six nucleotides, referred to as “6mers,” which are particularly toxic to cancer cells. This finding emerged from an exhaustive study where scientists tested all 4,096 possible combinations of these nucleotide sequences, eventually identifying the most lethal ones, which are rich in guanine (G) nucleotides.