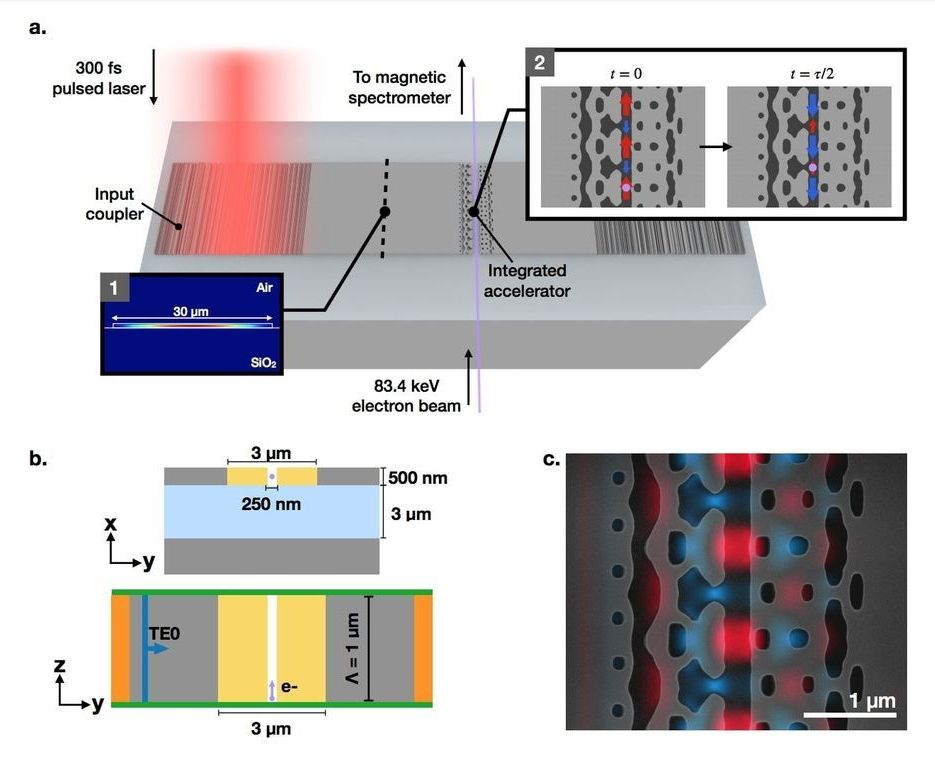

Dielectric laser accelerators (DLAs) provide a compact and cost-effective solution to this problem by driving accelerator nanostructures with visible or near-infrared (NIR) pulsed lasers, resulting in a 10,000 times reduction of scale. Current implementations of DLAs rely on free-space lasers directly incident on the accelerating structures, limiting the scalability and integrability of this technology. Researchers present the first experimental demonstration of a waveguide-integrated DLA, designed using a photonic inverse design approach. These on-chip devices accelerate sub-relativistic electrons of initial energy 83.4 keV by 1.21 keV over 30 µm, providing peak acceleration gradients of 40.3 MeV/m. This progress represents a significant step towards a completely integrated MeV-scale dielectric laser accelerator.

Dielectric laser accelerators have emerged as a promising alternative to conventional RF accelerators due to the large damage threshold of dielectric materials the commercial availability of powerful NIR femtosecond pulsed lasers, and the low-cost high-yield nanofabrication processes which produce them. Together, these advantages allow DLAs to make an impact in the development of applications such as tabletop free-electron-lasers, targeted cancer therapies, and compact imaging sources.

They have designed and experimentally verified the first waveguide-integrated DLA structure. The design of this structure was made possible through the use of photonics inverse design methodologies developed by the team members. The fabricated and experimentally demonstrated devices accelerate electrons of an initial energy of 83.4 keV by a maximum energy gain of 1.21 keV over 30 µm, demonstrating acceleration gradients of 40.3 MeV/m. In this integrated form, these devices can be cascaded to reach MeV-scale energies, capitalizing on the inherent scalability of photonic circuits. Future work will focus on multi-stage demonstrations, as well as exploring new design and material solutions to obtain larger gradients.