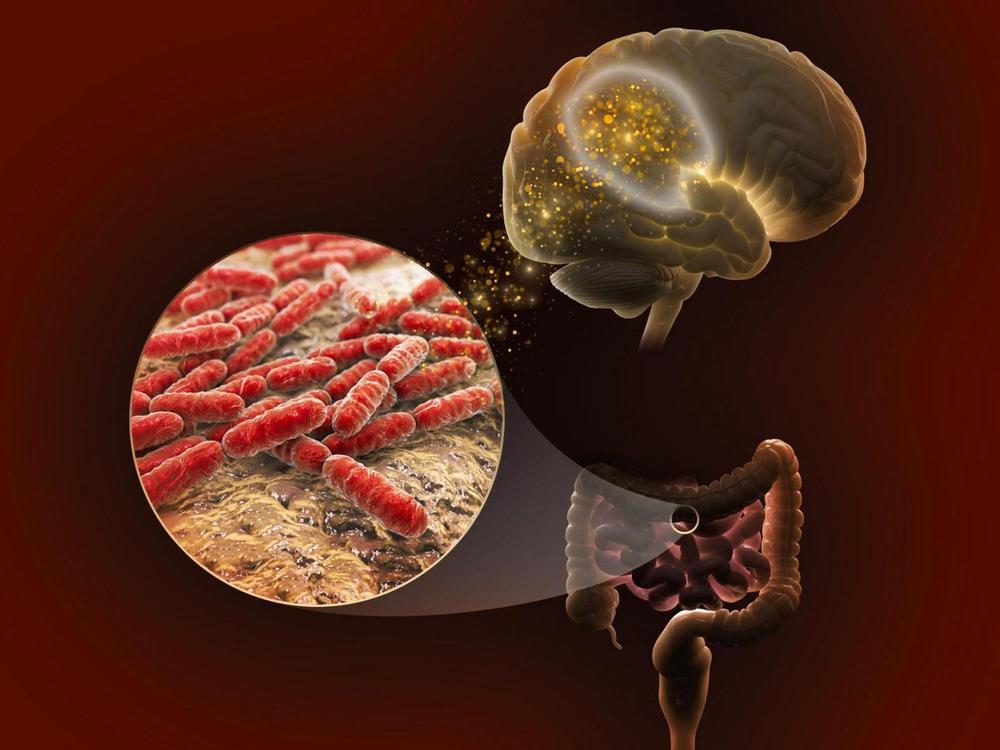

New research from an international team of scientists has tracked a compelling series of connections between the gut microbiome and memory. Using a novel mouse model engineered to simulate the genetic diversity of a human population, the study illustrates how genetics can influence memory via bacterial metabolites produced in the gut.

Over the past few years there has been significant research interest in the relationship between memory, cognition and the gut microbiome. While certain families of bacteria that live in our gut have been implicated in memory function, this new study set out to investigate the connection from a different angle, starting with the role genetics play in this relationship.

“To know if a microbial molecule influenced memory, we needed to understand the interaction between genetics and the microbiome,” explains co-corresponding author on the study, Antoine Snijders.