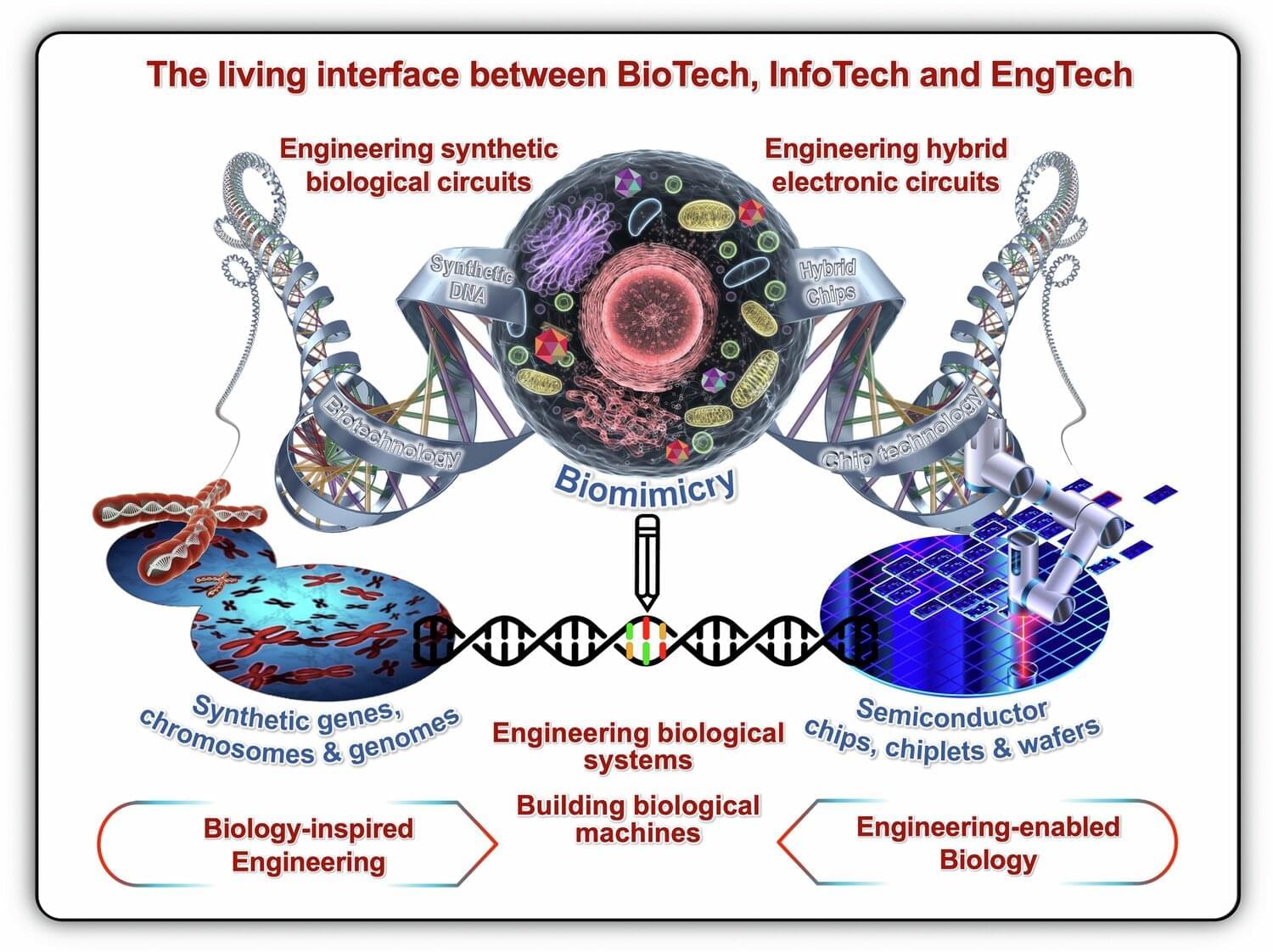

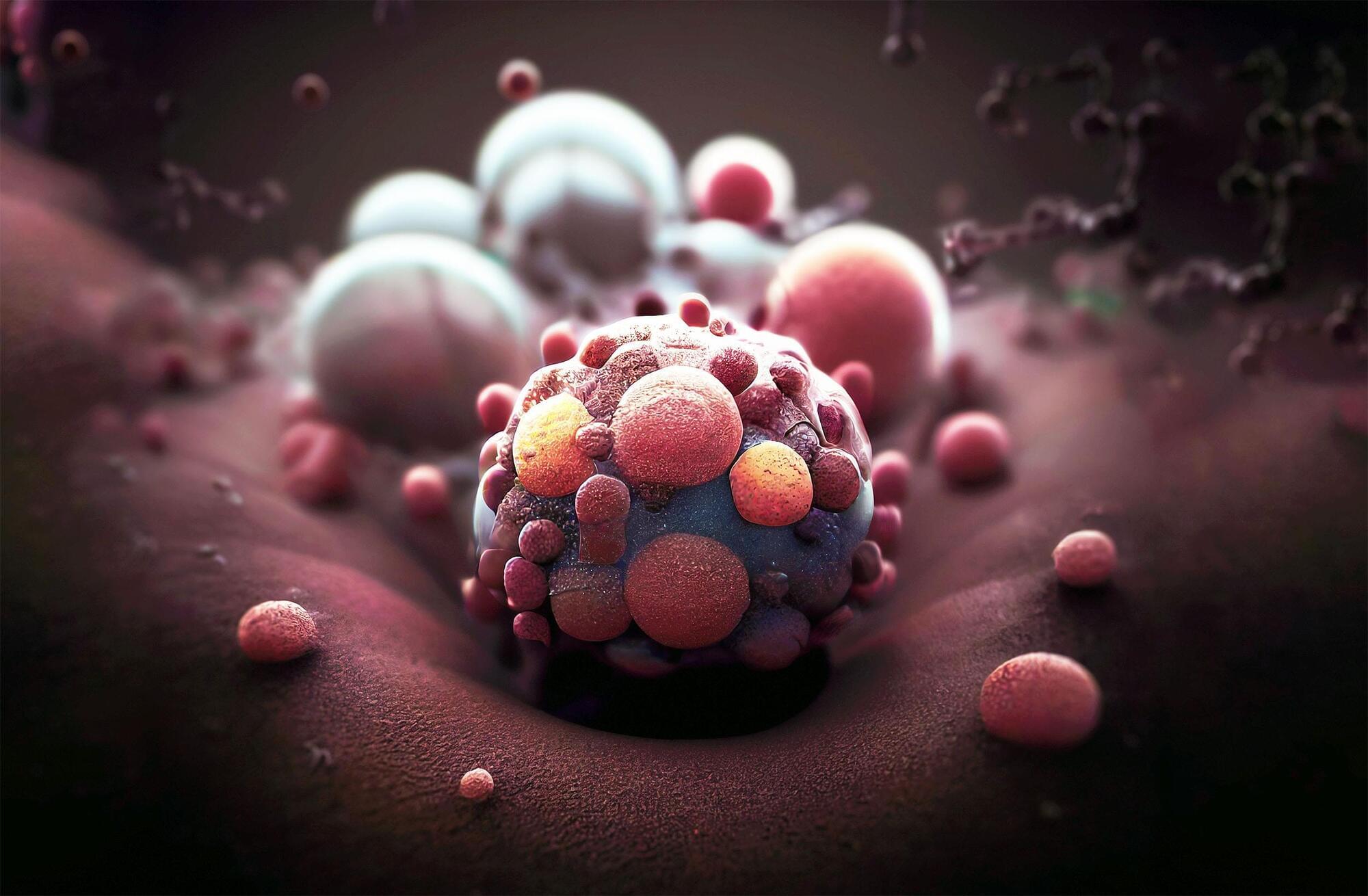

Australian researchers are turning to nature for the next computing revolution, harnessing living cells and biological systems as potential replacements for traditional silicon chips. A new paper from Macquarie University scientists outlines how engineered biological systems could solve limitations in traditional computing, as international competition accelerates the development of “semisynbio” technologies.

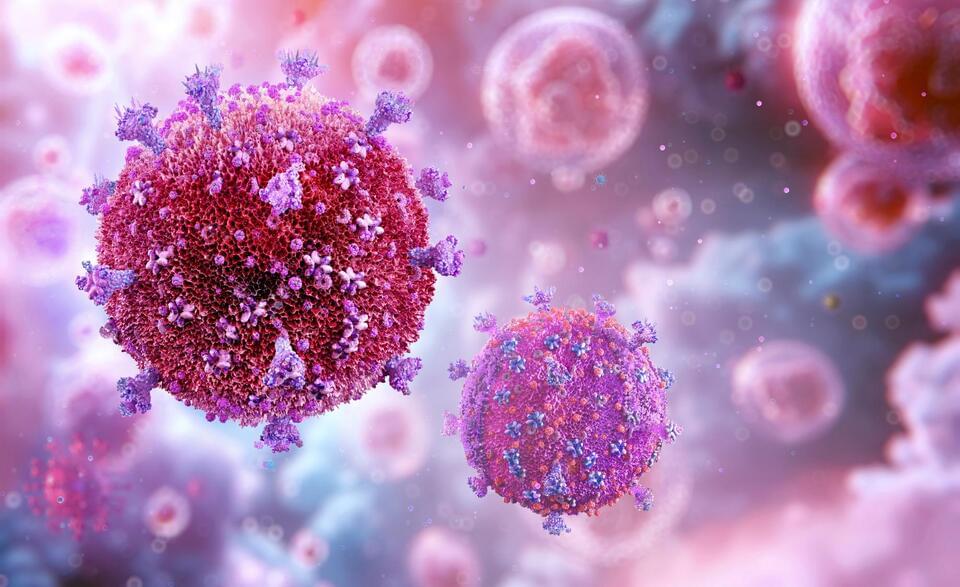

Living computers, organs-on-a-chip, data storage in DNA and biosecurity networks that detect threats before they spread—these aren’t science fiction concepts but emerging realities. A team from Macquarie University and the ARC Center of Excellence in Synthetic Biology (COESB) has explored this convergence of biological and digital technologies in a Perspective paper published in Nature Communications.

The Macquarie University authors—Professor Isak Pretorius, Professor Ian Paulsen and Dr. Thom Dixon (who are also affiliated with the ARC Center of Excellence in Synthetic Biology), Professor Daniel Johnson and Professor Michael Boers—draw on decades of combined experience to explain why harnessing bio-innovation can proactively shape the future of computing technology.