If Dr. Ken Berry actually meant to say that you need to eat saturated fat for your nerves and brain, he flunks Biochem 101. First of all, your body can make all the saturated fat you need out of carbs and proteins. You don’t need to eat ANY saturated fat. Second, the most common fatty acid in your brain is the polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) called DHA, which you DO need to eat, because you can’t make it from non-fats (you need to eat it or EPA in things like seafood, or at least the precursor omega-3 PUFA called ALA in cold-climate plants.) Ironically enough, ALA is common in Canola oil, which Dr. Berry deprecates, but not in the tropical plant oils that he likes. More on that later.

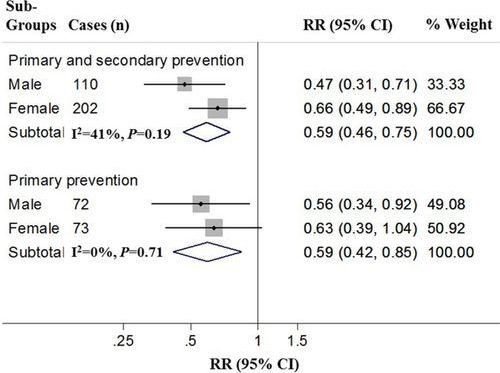

A diet with a lot of saturated fat is NOT the best for the heart. The American Heart Association continues to recommend low saturated fat diets (with the missing sat-fat replaced by mono and polyunsaturated fat, not by carbohydrates) because the evidence from animal and human trials and even properly controlled epidemiology, shows these the best diets (see reference below—an extensive review of meta analyses [1]). Examples are the DASH hypertension diet and the closely-related Mediterranean diet (which has lots of olive oil for monounsaturated fatty acid, and seafood for DHA). If Dr. Berry thinks he has something better than the Mediterranean diet for longevity, what is his direct evidence?

Saturated fat, of course, is used by the body to make cholesterol (you don’t need to eat any cholesterol for this reason), and it does raise cholesterol levels and it does increase atherosclerosis in nearly every controlled prospective experimental model in animals and humans. This is the gold standard of evidence in medicine.

One can go only so far with epidemiology, because occasionally when one bad thing (saturated fat) is heavily replaced for calories by another bad thing (certain carbohydrates) one detects no epidemiologic effect from changing just the first thing.

That happens with various high and low saturated fat diets around the world enough to make saturated fat look benign as a single input variable. It is not. Rather, what these studies really show is that replacing butter with sugar or high glycemic carbs gives you a diet equally bad for the arteries. One cannot see how bad that is, until one compares these with low-carbohydrate, low-saturated-fat diets, which are less common, but better. The double-negative tradeoff of carbs and saturated fats (where carbs are a statistical “confounder”) is one of those occasional cruel misdirectional things that happen with imperfectly controlled past-observations, but (again) it’s why biomedical knowledge consists of more than just epidemiology.

The saturated oils Dr. Berry recommends are by themselves on the edge of PUFA deficiency. This can be dramatic: for example the only way I know to give dogs atherosclerosis nutritionally, is to feed them just coconut oil for fat, and NO monounsaturates or PUFA. Apparently a little PUFA is extremely important for the heart, and larger amounts do no harm. There are hints that high PUFA diets are risks for certain cancers, but that merely underscores the need to get monounsaturates like olive and Canola where one can, and some PUFA foods. I know of no civilization that eats a lot of coconut oil that doesn’t eat seafood as well, so that combination is safe.

Canola oil is merely rapeseed oil bred to remove erucic acid and other potential toxins. It is high in monounsaturates and ALA and of all the plant oils is probably closest to optimal for human nutrition. Olive oil is probably better than Canola for frying, since ALA will oxidize, but Canola’s ALA is very important for vegans who need an omega-3 PUFA plant oil to convert to brain DHA. Seafood and olive oil are a fine replacement for Canola, but the person who cannot eat meat or seafood had better look for a baking and salad oil with ALA in it, and Canola oil is the best for this. Linseed oil is hard to digest and hard to work with, so that leaves Canola as the best omega-3 alternative for vegans. Dr. Berry never mentions his problem with Canola beyond saying it is GMO. But he is wrong there, as it doesn’t have to be. Canola as a product (1970’s) was created with hybrid not GMO techniques, and although GMO Canolas exist now, there also exist certified non-GMO and “organic” Canola oils which are labeled with a butterfly and tested to make sure no GMO Canola has crept in (there are tests available for this too complicated to go into here, but you can be sure).