The robot AgnathaX is modeled on the lamprey, a jawless, blood-sucking fish that’s been largely unchanged by evolution for the past several hundred million years.

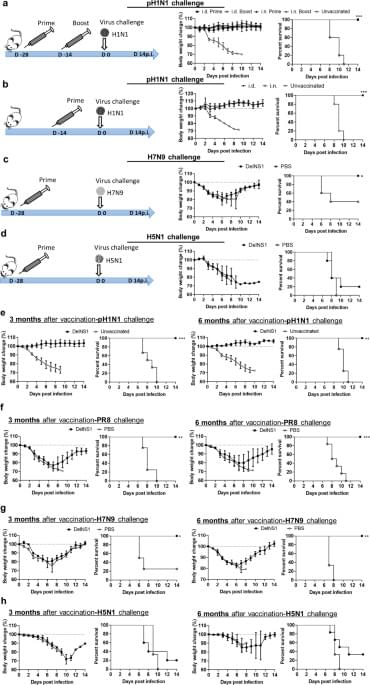

To test whether LAIV is effective via intradermal route, 106 plaque forming units (PFU) of DelNS1-LAIV was i.d. injected to multiple groups of mice. One of the groups was boosted with second injection at 14 days after the prime vaccination. Unvaccinated control mice were injected with the same volume of PBS. The mice were intranasally challenged with 10x LD50 of H1N1/415742Md at 28 days after primary vaccination. Both single dose and two doses of i.d. vaccination induced good protection with no weight loss and 100% survival after virus challenge (Fig. 1a). Comparing i.d. vaccinated mice with i.n. vaccinated mice, there was no difference in body weight loss or survival rate (Fig. 1a), which suggested LAIV i.d. vaccination offered the same protective efficacy as i.n. vaccination. Remarkably, a single dose of i.d. vaccination fully protected mice against virus challenge with 100% survival and no weight loss (Fig. 1b).

To test the broadness of i.d. vaccination-induced immunity, H7N9 (A/Anhui/1/2013m) or H5N1 (A/VNM/1194/2004) challenges were performed at 28 days after a single dose of i.d. vaccination. H7N9 challenge caused sharp weight loss and 60% death in PBS control mice, while the vaccinated mice were 3 days quicker in body weight recovery and had 100% survival (Fig. 1c). However, i.d. DelNS1-LAIV only rescued the survival rate to 20% among the H5N1-challenged mice, versus 100% mortality in the PBS group (Fig. 1d).

We then studied the longevity of i.d. DelNS1-LAIV-induced immunity by challenging the vaccinated mice at 3 or 6 months after vaccination. Firstly, homologues virus H1N1/415742Md challenge did not cause body weight loss, nor lethality 3 or 6 months after vaccination (Fig. 1e), suggesting the protective immunity lasted at least for 6 months; Secondly, all vaccinated mice survived against an antigenically different H1N1 strain (PR8) challenge and regaining body weight starting day 7 post challenge (7dpi) (Fig. 1f). All vaccinated mice survived after H7N9 challenge though with a similar degree of weight loss comparing to the PBS control mice (Fig. 1g). The immunized mice challenged by H5N1 at 3 or 6 months had 30% and 20% survival, respectively, with a similar degree of weight loss comparing to the PBS controls (Fig. 1h).

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have emerged as a promising treatment for patients with advanced B-cell cancers. However, widespread application of the therapy is currently limited by potentially life-threatening toxicities due to a lack of control of the highly potent transfused cells. Researchers have therefore developed several regulatory mechanisms in order to control CAR T cells in vivo. Clinical adoption of these control systems will depend on several factors, including the need for temporal and spatial control, the immunogenicity of the requisite components as well as whether the system allows reversible control or induces permanent elimination. Here we describe currently available and emerging control methods and review their function, advantages, and limitations.

As a living drug, CAR T cells bear the potential for rapid and massive activation and proliferation, which contributes to their therapeutic efficacy but simultaneously underlies the side effects associated with CAR T-cell therapy. The most well-known toxicity is called cytokine release syndrome (CRS) which is a systemic inflammatory response characterized by fever, hypotension and hypoxia (5–7). CRS is triggered by the activation of CAR T cells and their subsequent production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IFNγ, IL-6 and IL-2. This is thought to result in additional activation of bystander immune and non-immune cells which further produce cytokines, including IL-10, IL-6, and IL-1. The severity of CRS is associated with tumor burden, and ranges from a mild fever to life-threatening organ failure (10, 11). Neurologic toxicity is another serious adverse event which can occur alongside CRS (12).

Irvine, Calif., Oct. 12 2021 — The extract of the plant Corydalis yanhusuo prevents morphine tolerance and dependence while also reversing opiate addiction, according to a recent study led by the University of California, Irvine. The findings were published in the October issue of the journal Pharmaceuticals.

(Link to study: https://pharmsci.uci.edu/uci-led-study-finds-medicinal-plant…-epidemic/)

Over the past two decades, dramatic increases in opioid overdose mortality have occurred in the United States and other nations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the opioid epidemic has only worsened. The documented effects of YHS, the extract of the plant Corydalis yanhusuo, could have an immediate, positive impact to curb the opioid epidemic.

In the United States, animal health authorities are now on high alert. The US Department of Agriculture has pledged an emergency appropriation of $500 million to ramp up surveillance and keep the disease from crossing borders. African swine fever is so feared internationally that, if it were found in the US, pork exports—worth more than $7 billion a year—would immediately shut down.

“Long-distance transboundary spread of highly contagious and pathogenic diseases is a worse-case scenario,” Michael Ward, an epidemiologist and chair of veterinary public health at the University of Sydney, told WIRED by email. “In agriculture, it’s the analogue of Covid-19.”

As with the Covid pandemic at its start, there is no vaccine—but also as with Covid, there is the glimmer of hope for one, thanks to basic science that has been laying down findings for years without receiving much attention. Two weeks ago, a multinational team led by scientists at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service announced that they had achieved a vaccine candidate, based on a weakened version of the virus with a key gene deleted, and demonstrated its effectiveness in a field trial, in pigs, in Vietnam.

Circa 2020

TOKYO — As scientists the world over scramble to develop a vaccine for the coronavirus, Kyushu University professor Takahiro Kusakabe and his team are working to develop a unique vaccine using silkworms.

In his project, each of the worms is a factory that manufactures a type of protein to serve as the key material for vaccine production. Kusakabe said it is possible to create an oral vaccine and aims to start clinical tests on humans in 2021.

In a building on the Kyushu University campus in Fukuoka, in western Japan, “we have about 250,000 silkworms in about 500 different phylogenies (family lines),” Kusakabe said.

AI.Reverie offered APIs and a platform that procedurally generated fully annotated synthetic videos and images for AI systems. Synthetic data, which is often used in tandem with real-world data to develop and test AI algorithms, has come into vogue as companies embrace digital transformation during the pandemic. In a recent survey of executives, 89% of respondents said synthetic data will be essential to staying competitive. And according to Gartner, by 2,030 synthetic data will overshadow real data in AI models.

Full Story:

Facebook has quietly acquired AI.Reverie, a New York-based startup creating synthetic data to train machine learning models, VentureBeat has learned.

A Japanese startup at CES is claiming to have solved one of the biggest problems in medical technology: Noninvasive continuous glucose monitoring. Quantum Operation Inc, exhibiting at the virtual show, says that its prototype wearable can accurately measure blood sugar from the wrist. Looking like a knock-off Apple Watch, the prototype crams in a small spectrometer which is used to scan the blood to measure for glucose. Quantum’s pitch adds that the watch is also capable of reading other vital signs, including heart rate and ECG.

The company says that its secret sauce is in its patented spectroscopy materials which are built into the watch and its band. To use it, the wearer simply needs to slide the watch on and activate the monitoring from the menu, and after around 20 seconds, the data is displayed. Quantum says that it expects to sell its hardware to insurers and healthcare providers, as well as building a big data platform to collect and examine the vast trove of information generated by patients wearing the device.

Quantum Operation supplied a sampling of its data compared to that made by a commercial monitor, the FreeStyle Libre. And, at this point, there does seem to be a noticeable amount of variation between the wearable and the Libre. That, for now, may be a deal breaker for those who rely upon accurate blood glucose readings to determine their insulin dosage.

Aspirin is a blood thinner & can help head off heart attacks and strokes by preventing clots from forming in the blood vessels that lead to the heart or brain.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s proposed changes to recommendations for using low-dose aspirin to prevent a first heart attack or stroke closely align with guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.